Review: Sevdah: Elegy for a South Imagined

| Author | Malina Stefanovska |

| Genre | Nonfiction |

| ISBN | 978-1-952799-47-1 |

| Format | 88 pages |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | University Press of the South |

Reviewed by Robert J. Hudson

Sevdah, written in 2023 by Malina Stefanovska, captures “a feeling of intense longing that brings at the same time sadness and happiness. the Balkan version of the famed Portuguese saudade, nostalgia for a lost homeland, youthful dreams, past loves, or even for things that never were.” Choosing this as the title for her memoir, which bears the subtitle Elegy for a South Imagined, Stefanovska does wax nostalgic for the rich and eclectic “South” of her youthful summers, interwoven in six chapters and replete with genealogical vignettes, family legends, distant reveries, exemplary lives lived, and less than exemplary lovers.

But why should the story of one individual’s experience interest us? Why don’t we, like the author’s preteen son Ted from the first pages of her story, simply give in to the foreignness, the lack of context, the stifling heat and our inability to own anything in the narrative of another?

In 1580, at the conclusion of his introduction “To the Reader,” pioneering essayist and Renaissance man Michel de Montaigne forewarned and dismissed those who embarked to read him, admitting, “I myself am the subject of my book: it is not reasonable that you should employ your leisure time on a topic so frivolous and vain. Therefore, Farewell” (trans. M. A. Screech, Penguin Books, 1987). Montaigne would, nevertheless, continue over 107 essays and some 1,300 printed pages to demonstrate his thesis that “Every man bears the whole Form of the human condition” (ibid, p. 908), establishing himself as a model for humanistic introspection and the Essays as a veritable bible for living, as suggested by Orson Welles and others.

Stefanovska does not ask quite as much of her reader. In a beautifully recounted account of nostalgic sevdah, she conveys a sensual and sensory experience of her “South.” This South is, of course, South East Europe, the Balkans, the interest of SEEfest and our diverse readership. She recounts the summers of her youth spent in Bitola “at the southern tip of Macedonia,” where both of her parents and generations before them were born and lived their lives. This is the setting of Stefanovska’s cultural and familial memory. And truth is, as they say, stranger (and often messier) than fiction.

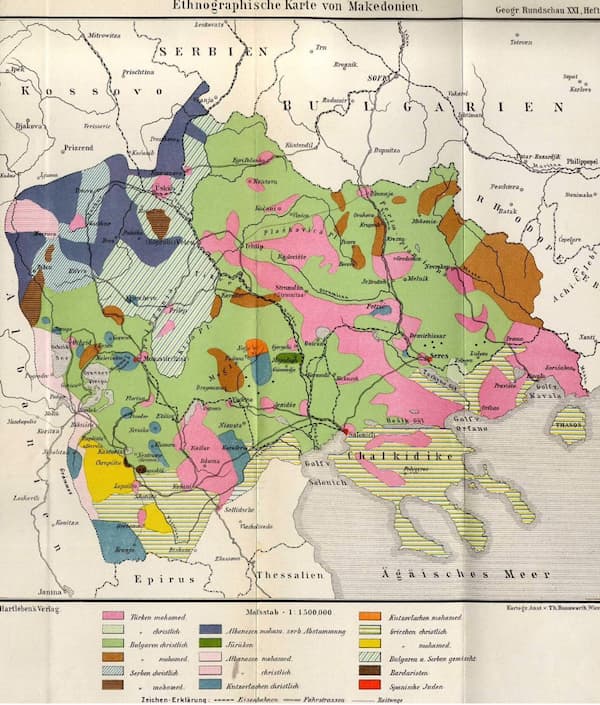

Could it be otherwise for Macedonia? In the French language, that of Stefanovska’s scholarship, the common noun “macédoine” is an antonomasia derived from the proper noun Macedonia and, in the culinary world, it is the term used for fruit cocktail or mixed vegetables. If we examine ethnographic maps of the region (like the one below from 1899), the origins of this idea of merging and integrating, while maintaining distinct identities, rings true for this region – as well as for Stefanovska’s account that blends (and not always neatly) Slavic, Greek, Vlach and Romani peoples, along with transient Africans, Arabs, Serbs and others. The Macedonia she describes is a vibrant mosaic of legend, myth, folklore, tradition, rite, common beliefs, colors, food, smells, etc.

Mosaic as metaphor here is deliberate. Bitola boasts some of the most remarkable examples of Ancient Greek mosaic (e.g., the UNESCO protected Heraclea Lyncestis). And Stefanovska is not indifferent to the deep, diverse past of this region, especially as she mentions Bitola as the birthplace of Filip the Macedonian, father of Alexander the Great. However, she does so almost in passing, relating how her own grandfather felt about sharing a name with this colossal figure from the past.

Sevdah is not a political history, but rather a familial history. Very little mention is made of the Greek or Bulgarian refusal to recognize Macedonian language, identity or ethnicity; however, she does include the story of a father slapping his ten-year-old son – the only ever time he would ever do so – for crying, in a mere act of mimesis with his classmates, when the Yugoslavian king was assassinated, which is telling.

Not a regional or political history, Sevdah remains anthropological as it deals with human relationships against the backdrop of a both mythified and palpable setting. Indeed, in an email exchange with Stefanovska, she admitted that the idea for the memoir germinated in part from her desire to teach a course at UCLA on border crossings in Europe, focusing particularly on the Romani.

In my teaching at Brigham Young University, I adopted her book for my European Studies seminar on “Regionalism,” as it offered rich and poignant first-hand anecdotal evidence to highlight the struggles, joys, values and interests of Macedonia and the peoples that inhabit this region. It was, I might add, an unmitigated success among my students, who would return to it in class comments throughout the semester.

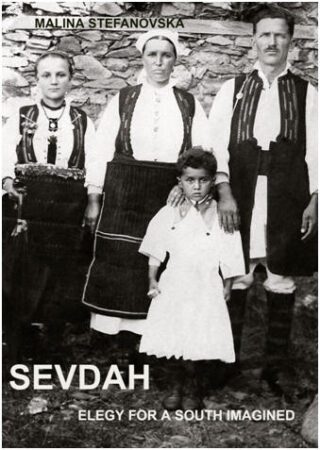

Above all else, Sevdah is familial. On its front cover, it bears a family photo of the author’s father as a child, standing with his older sister and parents, all donning traditional attire. As the one piece of “photographic evidence” in the volume, it is an image that the reader can return to frequently, with each new revelation from the author. In a sense, as memory builds upon memory, the memoir comes together somewhat like a Patrick Modiano novel, as a holistic image progressively develops.

Here, a handsome, blue-eyed Slavic pater familias stares through the lens of the camera into the eyes of the viewer, with an evident pride in his young family and hope to provide them a better childhood than his own – yet, with no idea, at the time of the photograph, that his ill-fated, ten-year trip to America would coincide with the Great Depression and that his beautiful teenage daughter (to the left of the photo) would die while he was away.

We also see the sternness of his wife, who “never sang, and told no stories,” and we begin to understand her jealousy and passion felt for the mystical man to her left who possessed so much more freedom to roam than she did. We even recognize the dark, penetrating gaze of the young boy who would grow from poverty to a diplomatic career, and one day become Stefanovska’s cherished father.

Stefanovska also explores her more affluent, Greek speaking maternal line, which is itself marred by a deep secret of family murder: her grandfather mysteriously shot and killed his son-in-law for reasons the author attempts to unravel. Along with tales of her maternal family, Stefanovska also shares the story of an admired paternal aunt, an effervescent woman with a “sunny temperament,” who overcame local gossip and judgment as a divorcée, socially deemed as a “loose, unleashed woman, living outside of the moral order” and something of a Slavic protofeminist.

As familiar as it is familial, Stefanovska’s memoir concludes with the story of an early love affair. As a student in Belgrade, she shared part of her life with a Roma man, whose shared interests in philosophy, poetry and politics – and South Balkan heritage – tragically gave way to distrust, possessiveness, alcoholism and physical abuse.

Never easy to read, Stefanovska’s vulnerability remains deeply impressive, offering a rare glimpse of shared humanity and an affirmation that not all stories have a happy Hollywood ending, that our lives are also defined by decisions to leave. Her tale is one of exiles, of roads taken and others abandoned.

Image: An older photo of the city of Bitola.

Along with the scent of mulberries and the admitted nostalgia induced even today by Turkish names, Stefanovska also tells of the emotional encounter as an adult in Paris, witnessing men bearing a heavy haul of Macedonian red peppers, pečeni piperki, at the Gare d’Austerlitz, and another gesture of a Macedonian father in the metro tenderly kissing his young son in a recognizable way, both of which transported the author instantly to the Bitola of her youth.

Drawing to a close with an account of her own motherhood, a topic that bookends her memoir, from young Ted to her adopted daughter Maya, we can recognize the truth that our memories define us and inform life’s decisions. Snapshots and static histories are helpful, but an accounting of the process and the layers of humanity are far more valuable to understanding.

Like Montaigne, who expressed the impossibility of painting a sunset, Stefanovska is not attempting to paint a realistic portrait here; her aim is to capture “the passage” of becoming, passing from one state to the next. She elucidates snippets of memory that engender sevdah. She recounts a story of a South that no longer exists, and indeed, may never have existed, except in imagination.

Sevdah is available for purchase, in both English and French, from the University Press of the South.

Robert J. Hudson is a professor of French literature, cinema and culture in the Department of French & Italian at Brigham Young University.

Born in Arkansas and raised in Kentucky, Bob feels about his own “South” in ways that are quite akin to the ways Malina does about hers. Educated at UCLA, he is a scholar and translator of poetic verse from Renaissance France, focusing particularly on the importation of the Petrarchan sonnet from Italy to France, and the ways that literature and film serve autobiographical ends.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs, as well as our mission to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Pitch The SEEfest Review

The SEEfest Review is now accepting pitches on a rolling basis for essays and critiques covering film, literature, art, history, and music. Please review our guidelines before sending us your pitch.

We look forward to hearing from you. Due to the volume of pitches we receive, we may be unable to reply to each pitch, but we will do our best.

Details for Pitching The SEEfest Review

The SEEfest Review welcomes submissions for film and literary reviews that explore the complexity of South East Europe. We are also open to educational articles particularly ones that raise awareness of historically marginalized populations of people who live in South East Europe or are part of the diaspora.

Pitch Guidelines

The SEEfest Review now accepts pitches on a rolling basis for essays and criticism on film, literature, art, history, and music. Please note that pitches are short summaries of who you are, why you want to write this review, and how your angle can offer a unique examination of the topic at hand. Pitches are not full submissions.

Please review our published reviews for an idea of what we are looking for. In general, we prefer film, literature, and play reviews rather than, say, historical articles or general trends in the film industry. That said, we occasionally accept the latter as well, especially if they resonate with our mission. We ask that your final article be between 500 and 1,500 words.

To pitch us, please complete this form titled “Pitch The SEEfest Review.” Please wait for a response from our team before you pitch us again. Thank you.

We welcome simultaneous submissions, but please notify us if your piece gets selected for another publication as soon as you know. That way we don’t fall in love with a pitch that is no longer available for us to pursue.

You should hear from us within six weeks.Should you be rejected, please know that you can still continue to submit future pitches to us. If your pitch was accepted, we will be in touch with you to offer editorial guidance as you complete your article.

About Us

If you are new to SEEfest, welcome. Please review our mission to familiarize yourself with the kinds of stories we long to read and share with the world.

The SEEfest Review is an online publication part of the annual South East European Film Festival (SEEfest). Each spring, SEEfest educates about and promotes the cultural diversity of South East Europe through its annual presentations of films from this region and year-round screenings and programs. SEEfest organizes conferences and retrospectives, serves as the cultural hub and resource for scholars and filmmakers, and creates opportunities for cultural exchange between Southern California and South East Europe.

Visit the footer and subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news and film festival updates from SEEfest.

As a nonprofit, we also welcome your support in keeping international cinema part of the Los Angeles film scene.

Review – Romeo & Juliet: Love is a Fire

“I can’t remember seeing so much humor in a production of Romeo & Juliet ever before – which was a delight.”

A Review of Romeo & Juliet: Love is a Fire

Santa Monica Playhouse

By Catharine Dada, PhD.

This revisioned dynamic production Romeo & Juliet: Love is a Fire blends dance and a paired down, and sometimes cross-gendered cast to create Shakespearian magic on a blank stage. The verse is served well by an exceptional ensemble of actors, and under the direction of Neno Pervan – a native of Sarajevo, Bosnia & Herzegovina – the play moves along at an excellent pace. I can’t remember seeing so much humor in a production of Romeo & Juliet ever before – which was a delight.

We’re welcomed into the theatre with a sensual pairing of Romeo & Juliet as dancers already onstage – each costumed as one half of the whole that they represent together. Each knowing the other but not yet seeing each other … until they do.

The eclectic costumes in the show are more a mark of each character’s persona rather than fitting into any single identifiable time period. It was through the power of the performances that we knew exactly where we are at all times – even though the stage is kept bare. This is proof that when the performances are strong enough – we only need a good actor and a blank stage to bring great drama to life.

Stand out performances include Charlotte Williams Roberts – whose Prince Escalus owned not just the Playhouse Stage, but her strength seemed to expand to include several blocks of Santa Monica real estate as well. Robert’s clear command of the verse and her majestic presence were wonderful to behold.

The double casting of Tory Devon Smith – as both the mercurial Mercutio and the staid yet temperamental Capulet – was inspired. It was a joy to watch this actor shift his center of gravity (and gravitas) depending on the age and relative youthfulness of the character he was portraying. Appreciating an actor who could so skillfully join his physicality with the verse was a treat.

As Friar Laurence Alan Corvaia was able to bring abundant creativity to the role, occasionally breaking into bouts of fluent Spanish – and often for longer than expected! However, it was my particular delight (having forgotten most of my high school Spanish) that I could easily follow the gist of what he was saying – his clear voice navigating the waves and undulations of English just as easily as with his mother tongue. Corvaia’s Friar was well grounded, providing a strong contrast to the impetuosity of the youthful lovers – and rooted in the clear hope of what the power of true love could accomplish.

The cross-gender casting of Benvolio & Balthasar worked surprisingly well – with Madeline Shallan inhabiting her masculine characters with strength, grace and presence.

Gavin Mulcahy’s triple casting as Tybalt / Paris / Montague also stood out. His rich & gravelly voice lent itself well to three distinct characters.

Sika Lonner’s Nurse brought some more humor & warmth to the stage – which she balanced with her steady and clear Lady Montague.

Madison Hansen cut a graceful figure as Lady Capulet – furious with the outrageousness of her daughter’s disobedience – and yet herself like a frightened animal, trapped in an abusive marriage. Her gossamer fluid costume spoke of wealth – but her presence spoke of the plight of women throughout history, duty bound to their husbands – whatever his whims may be.

Annalisa Cochrane’s Romeo is beautifully grounded in a sexually-driven masculinity. A magnetic and charismatic presence, she navigates the changing territory from her love of Rosaline to that of Juliet with a deep understanding of the emotional depth that unbridled passion requires.

Juliet was played in the performance I saw by Chantel Adedeji – who balanced her impetuous innocence with doe-eyed wonder.

You might think you know how the story ends – and of course that doesn’t change – but there is one final delight – which involves the dancers Laura Ann Smyth as a Juliet and Chris Smith as a Romeo. Go and see it – you’ll think about the “what if’s” in this classic tale in a whole new light – and enjoy a tale of the enduring power of love and the human spirit brought to life by an exceptional ensemble along the way.

Running for two more weeks at the Santa Monica Playhouse, 1211 4th Street, Santa Monica, CA 90401

November 9, 16, 18th at 8pm, and Novmber 11, 12th at 2pm.

For tickets go to: Tickets for Romeo and Juliet – Love Is a Fire in Santa Monica from ShowClix

Dr. Catharine Dada received her Ph.D. in Religious Studies from the University of Kent, Canterbury, UK. The focus of her research was on modern experiences of spirituality in Western theatre. She received her first degree in Theatre from LMU and subsequently trained as a classical actress at the prestigious Bristol Old Vic Theatre School in England.

Catharine has acted in several productions for the Royal Shakespeare Company -performing at theaters at Stratford and at the Barbican in London, as well as playing leading roles in many repertory theaters throughout the UK. More info here and here.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs, as well as our mission to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Review – Glass Onion

Set in Greece, Rian Johnson’s slick whodunnit is a repudiation of the tech craze, influencer culture, class privilege, and American hegemony abroad.

Warning: Contains Spoilers for Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery

By Vanessa Bloom

“I like the glass onion, as a metaphor. An object that seems densely layered, but in reality, the center is in plain sight.” Detective Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig) is back, and don’t let his distinctive twang distract you from the truths he has to tell. In this anticipated sequel to Knives Out, Blanc returns to solve yet another mystery, this time at billionaire Miles Bron’s (Edward Norton) private island in Greece (the film was shot in Greece and Serbia). Like the titular glass onion itself, this film has layers of meaning for the audience to peel back, everything from class differences to American influence in the world at large.

Before anyone argues that it’s “not meant to be that deep,” let me remind you that to assume so would be to underestimate writer/director Rian Johnson. From the biting sequences critiquing the White American Liberal in the first Knives Out (“‘Immigrants Get the Job Done!’” one character quotes while another replies, “I love Hamilton”; later in the film, these same characters threaten to report the heroine’s undocumented mother to I.C.E.) to Johnson’s real-life defense of Asian-American actress Kelly Marie Tran during the racist attacks she endured after starring in Star Wars VIII: The Last Jedi, Johnson knows what he’s doing.

He’s well aware of both his audience and himself, and has over a million followers on Twitter where he interacts with fans and trolls his haters (most notably conservative poster boy Ben Shapiro). Born into privilege himself (his childhood home in San Clemente, California was listed for $7.7 million in 2018) Rian Johnson nevertheless possesses an uncanny awareness of injustice in the world, and isn’t afraid to call it out when he sees it.

Johnson’s sensibilities are written out in his latest film, the Knives Out sequel Glass Onion. A fresh cast of American characters descend into chaos as their 21st century lives collide in Greece: the brilliant scientist Lionel Toussaint (Leslie Odom Jr.); image-obsessed politician Claire Debella (Katherine Hahn); former model turned loungewear entrepreneur Birdie Jay (Kate Hudson) and her long-suffering assistant Peg (Jessica Henwick); and gun-toting alpha male influencer Duke Cody (Dave Bautista), accompanied by his girlfriend who’s using him for her own political aspirations, Whisky (Madelyne Cline).

Each character has their secrets and they’re all part of a former friend group split apart when Andi Brand (Janelle Monáe) had a falling out with Miles over the tech company they created together. Janelle Monáe shines as the co-star of this movie, commanding the screen and demanding respect – from the other characters and the audience alike. She and Craig as Blanc make a formidable pair, her character’s highfalutin big-city accent contrasting delightfully with his Southern drawl. For his part, Edward Norton as Miles Bron plays up the Elon Musk-esque aspects of his character, the big ideas, the tech jargon, and the constant push for “progress” no matter what the cost (“I want to be responsible for something that gets talked about in the same breath as the Mona Lisa,” Miles declares).

The backdrop of Greece is something Johnson himself said was a creative decision to separate this film from its predecessor, Knives Out, set in the American state of Virginia. However, Johnson does more than show the beautiful scenery, he uses it to illustrate characters’ privilege. Glass Onion is set during the Covid-19 Pandemic, and like so many real-life well-off Americans who fled cities to move to beautiful yet typically lower-income areas, Miles Bron has a mansion on a Greek island and invites his American friends for a mask-free weeklong soirée. No matter that the staff driving or serving them have to be masked; Covid-19 is their problem for being poor.

Once at his mansion (which features a gigantic glass onion on the roof) we learn of Miles’ real plans: pushing his tech company’s hydrogen powered fuel to market as quickly as possible, despite warnings it’s highly explosive and not safety tested. Miles embodies the “move fast and break things” mentality that began with California’s tech elite in Silicon Valley and has since infected the world at large. The fact that Greece is thousands of miles from Miles’ company headquarters doesn’t protect the country from his machinations; it’s revealed later on that Miles is secretly running his mansion on the new, untested energy system. American dominance globally is perpetuated by wealth and status, and Miles Bron is no exception – he’s the rule.

The conflict between Miles’ friend group and the now-outcast Andi is also another excellent example of Johnson’s keen eye for spotting social inequality. Andi, a Black woman, is self-made and grew up lower-class in the American South. She changed her accent to fit in with her wealthy mostly white Northerner friends. So it makes sense Andi’s the target when the friend group sours. As we learn later, she was the only one to actually call Miles out, and he continued using her ideas to make the company successful. The others, basically writing Andi off as the Angry Black Woman stereotype, fall in line behind Miles.

Johnson knows a thing or two about mob mentality: five years later, he still limits his Instagram comments from when Star Wars fans spammed him with hate after the release of The Last Jedi in 2018. In Glass Onion, he does not hold back in portraying how Miles and his friends ostracized Andi, ultimately murdering her. Johnson also isn’t afraid to describe exactly what these characters are, through the words spoken by Benoit Blanc: “I expected complexity. I expected intelligence. I expected a puzzle, a game. But that’s not what any of this is. It hides not behind complexity, but behind mind-numbing obvious clarity.” The obvious clarity is that the characters of Glass Onion are a cross-section of the American elite, all scrambling to appease the current billionaire who’s going to fund their next project and get them up a couple of rungs up the ladder.

Everyone else is collateral, disposable beings that exist to serve the larger goal – not only Miles and his friends’ personal ambitions, but the more opaque notions of preserving wealth, stymying social advancement for the lower classes, and American influence abroad. Only when our heroes step in is justice delivered for the late Andi; even then, the rest of Miles’ posse don’t really learn anything. They only switch to being against Miles once it’s bad for their own reputations.

In Glass Onion, the American Dream curdles under the Greek sun. Johnson is an excellent, insightful writer, not only crafting a classic mystery but giving it a deeper meaning that’s more relevant than ever in the 21st century. While tech continues to grow, influencers influence, and billionaires profit off low-wage labor, the division between the wealthy and the poor also continues to grow. Simultaneously, American influence has spread across the globe, and shows no sign of stopping. Nowhere are all these issues on better display than in Glass Onion, where, like a master chef, Rian Johnson peels back the story … revealing that the outer layer and the core are one and the same.

Glass Onion is available on Netflix.

Vanessa Bloom is an emerging writer, educator, and filmmaker from Orange County, California. She was adopted from China in 1999, and her mom’s side is Jewish from the Balkans while her dad’s is Christian from the American Midwest. Her family is not only multiracial and multicultural, but also multifaith! With such a colorful background, Vanessa loves telling stories and has written everything from coming-of-age dramas to horror comedy. Her favorite type of story is one that makes her laugh. Vanessa has a B.A. in history and a teaching credential in social science from CSU Long Beach. She also is proud to be a Los Angeles Community Leader for The LUNAR Collective, an organization for and by Asian Jews. Find her work at linktr.ee/vanessabloom.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs, as well as our mission to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Review – Pueblo Espíritu

Pueblo Espíritu devised by Organización Secreta Teatro

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

Clutching their face masks and backpacks, four exhausted individuals stumble into a strange forest. Nerves clearly shot, they spray disinfectant at each other and come to blows, but not before a fifth person appears, coughing so hard that they fall to the ground. In the ensuing silence and weight of paranoia, the individuals surrender to their fatigue—and to the spirits of the surrounding land.

So starts Pueblo Espíritu (“Spirit Town”), a wordless multimedia performance devised by Mexico City’s experimental Organización Secreta Teatro and directed by company founder Rocío Carrillo. Wordless, yet carried by character grunts and overhead music swelling with drums and chants, the ensemble (Beatriz Cabrera, Alejandro Joan Carmarena, Brisei Guerrero, Stefanie Izquierdo, Ernesto Lecuona, Mercedes Olea, and Jonathan Ramos) remake their post-apocalyptic environment by communing with the wildness of the spiritual world and returning to embodied material-making practices, such as weaving and ceremonial medicine.

There’s still peril in the spiritual world, though, and tension between physical, social, and spiritual boundaries explored more through dream logic than by way of any definitive storyline. A gloriously painted bird-entity (Carmarena) seems to have power over the dead, but is also susceptible to the tricks of a feral girl (Izquierdo) who appears to be negotiating her status as human, animal, and warrior.

A medicine man (Ramos) leads the group in a ceremony where a fierce feminine divinity arises and dances amidst dangerous laughter (Guerrero), while afterwards an archer and hunter (Lecuona) deals with a terrifying apparition and deer-like spirit (Cabrera) in what could be a nightmare or the birth of something more sinister.

An elderly woman (Olea) observes and absorbs much of this pain, sometimes serving as a guide and other times as a witness.

Carrillo’s direction steers the ensemble between swift dances, tender embraces, and erotic animalistic movements to portray the porous interdimensionality of the worlds. Erika Gomez’s design conjures up a lavish natural world, yet one still marred by civilization and prone to interruption. The mask and makeup elements are particularly inspired and detailed, turning ordinary humans into supernatural creatures in mere moments.

If I could change one thing about the production, I would wish for better audio quality or live performance of the music. While the melodies are epic and reminiscent of traditional indigenous songs, the overheard sound and its slightly tinny quality could be distracting, and moments of the actors lip-synching or chanting along with the soundtrack lent me a slight feeling of uncanny disembodiment, a friction between the digital and the live performance clashing with my visual and aural senses in a way that took me outside of this otherwise enchantingly bewildering world.

However, this friction made silences onstage and any subsequent ensemble noises (sans sound) even more poignant and profound, as the echoes faded and wrapped the audience within a reverent stillness.

While Pueblo Espíritu has a limited run at the Latino Theater Company with only five performances until May 7, the ensemble will also be performing Las Diosas Subterráneas (“Subterranean Goddesses”), an experimental adaptation of the Greek myth of Persephone (the maiden goddess kidnapped by the god of the underworld) juxtaposed with the story of Luz García, a character based on real-life women kidnapped by human traffickers.

With these two stories intertwining, the ensemble seeks to portray the story of mothers looking for their missing daughters while finding strength in community. With these two performances, Organización Secreta Teatro gives us an entryway into vigorously magical worlds, inviting us to examine our own relationships with spirit, land, and power.

Pueblo Espíritu had five performances, concluding on May 7.

Las Diosas Subterráneas performs the following week, on Wednesday, May 10 at 8 p.m.; Thursday, May 11 at 8 p.m.; Friday, May 12 at 8 p.m.; Saturday, May 13 at 8 p.m.; and Sunday, May 14 at 4 p.m.

Tickets range from $22–$48, except opening night (May 3), which is $58 and includes pre- and post-show receptions. The Los Angeles Theatre Center is located at 514 S. Spring St., Los Angeles, CA 90013. Parking is available for $8 with box office validation at Joe’s Parking structure, 530 S. Spring St. (immediately south of the theater).For more information and to purchase tickets, call (213) 489-0994 or go to www.latinotheaterco.org

Pueblo Espíritu photos by Ángela Chapa

Las Diosas Subterráneas photo by Erika Gómez

Reviewer Amanda L. Andrei is a Filipina Romanian American playwright, literary translator, and teaching artist residing in Los Angeles by way of Virginia/Washington DC. She writes epic, irreverent plays that center the concealed, wounded places of history and societies from the perspectives of diasporic Filipina women, and she translates from Romanian and Filipino to English. For more information on her work and upcoming events, visit: www.AmandaLAndrei.com

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs, as well as our mission to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Review – I Do Not Take My Name for Granted

I Do Not Take My Name for Granted: Four Short films by Saodat Ismailova

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

March 6, 2023, at REDCAT, Roy and Edna Disney CalArts Theater

The longer you gaze at the steep cliffs, the more you start to see shapes of women. Vintage footage of Soviet tanks gives way to the dilating pupil of a tiger. And the image of women—whether preserved through oral tradition, a nation’s cinema, or a fading ritual of movement on a mountain—emerges from deep within the cultural memory of Saodat Ismailova’s four short films at REDCAT, curated by Jheanelle Brown.

Gulaim (2014) starts the journey, a monologue of the heroine Gulaim from the Central Asian epic Qyrq Qyz (40 Girls), a narrative preserved in the oral folklore of the Qaraqalpaqs, a Turkic group native to Karakalpakstan, an autonomous republic within Uzbekistan.

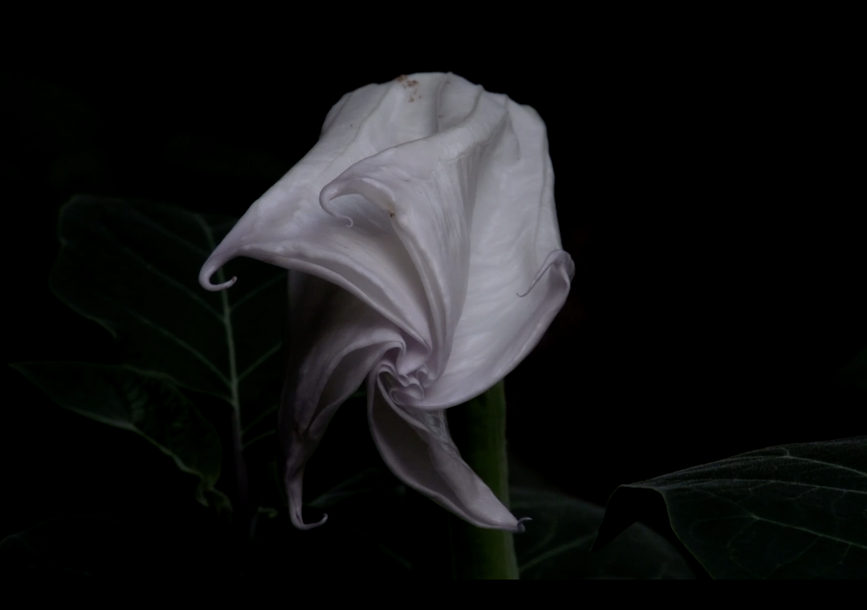

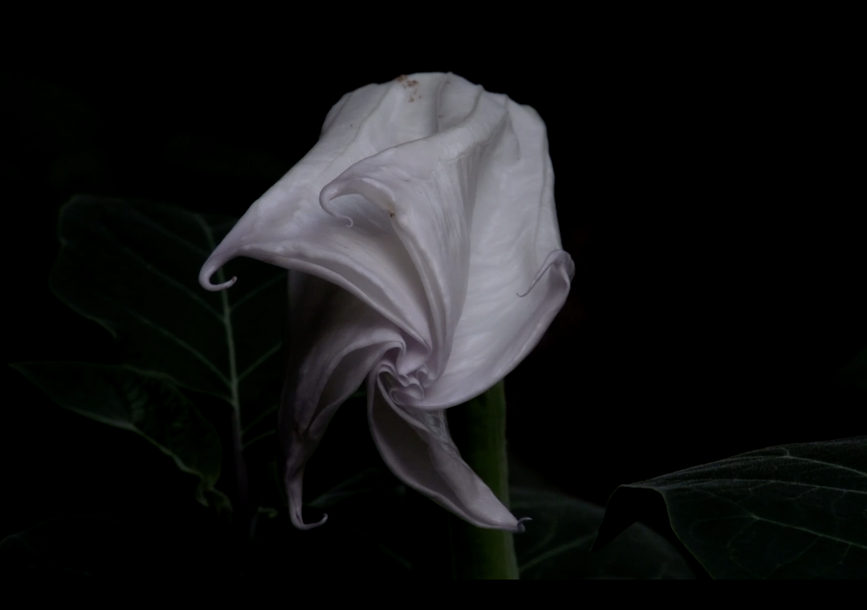

Cliffs bathed in setting sun rays mingle with closeups of a young woman’s face and hair, the blue flanks of a horse, and a blooming moonflower, as a narrator relates how her father used to shower her with affection in her childhood. Now she refuses to marry a man he has chosen for her, marking a new chapter in her life as she moves from favored daughter to something more liminal and uncertain.

The breathtaking landscapes and intimate details of hair, clothing, and animals—as well as surreal images of veils, chainmail, and a theatrical stage—draw the audience into both large and small scales of beauty and betrayal on ancient and modern levels.

The following film, The Haunted (2017), depicts an imaginary encounter with a Turkestan tiger that became extinct due to Russian colonization of Turkestan in the 1940s.

As sportsmen and military personnel hunted the tigers and the sacred animal’s habitats were converted into land for cotton crops, the tigers were declared extinct in the 1970s. A female voice quietly yet intensely mourns the loss of sacred love and connection over images of grainy black-and-white footage evoking colonization, which are juxtaposed against intense closeups of a live tiger’s eyes, whiskers, and deep fur.

Shots banks its former habitat are motionless amidst the river banks’ greenery, as if waiting for the empty space to once again be filled with soft pawprints and striped skin.

Her Five Lives (2020), commissioned as part of Asian Film Archive’s Monographs, a series of essays on Asian cinema, presents five different archetypes of heroines in Uzbek cinema from the past century, starting with Vyacheslav Viskovsky’s 1925 film, The Minaret of Death, based on a 16th century myth of the Bukharans, an ethnoreligious Jewish group in Central Asia.

Early silent black-and-white film of women as victims of patriarchy transitions into portrayals of women under communism, reform, perestroika, and eventually independence (albeit a confused one).

In contrast to the first two films, this short is faster paced and draws upon more recent cultural memory in the form of archival film, with some of the last footage from Ismailova’s 2014 film, Forty Days of Silence. It’s exciting to watch the transformation of the cinematic portrayal of Central Asian womanhood, making one wonder how to access and watch these films now.

The final film, Chillpiq (2018), depicts a group of girls climbing the ruins of Chillpiq, an ancient funerary structure founded by Zoroastrians and located in Karakalpakstan.

They surround a flag pole, tying rags and circling the pole in the light of the fading sun. From a visual standpoint, the film seems more like a documentary, grounded in realism and with steady shots of the young women as they climb up the mountain. But as they conduct their ritual in silent determination, there arises a feeling of quiet glory that only comes through steadfast devotion.

These contemporary women somehow know how to honor the earth and the unseen, and the earth and unseen return the honor.

While Ismailova’s films have been showcased in museums and film festivals, with her work currently held in collections of Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, this one-night event marked the first time that her films have been screened theatrically in Los Angeles.

Her films are a treasure, giving outsiders a rare glimpse into Central Asian ritual, history, and personhood. To see them in a cinema is a reverent experience, offering the chance to immerse ourselves in our own cultural memories and re-examine the myths, landscapes, and archetypes that we hold dear.

Reviewer Amanda L. Andrei is a Filipina Romanian American playwright, literary translator, and teaching artist residing in Los Angeles by way of Virginia/Washington DC. She writes epic, irreverent plays that center the concealed, wounded places of history and societies from the perspectives of diasporic Filipina women, and she translates from Romanian and Filipino to English. For more information on her work and upcoming events, visit: www.AmandaLAndrei.com

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Review: Night truck driver

Night truck driver, By Marcin Świetlicki

Translated from Polish by Elżbieta Wójcik-Leese

Poetry

ISBN 9781938890802

128 pages

Bilingual: Polish and English on facing pages

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

The world drips. Caught in some kind of thaw, circling a winter on the verge of melting into a dream, or a dream solidifying into a cold city, Marcin Świetlicki’s Night truck driver (Kierowca nocnej ciężarówki) translated by Elżbieta Wójcik-Leese, immerses us into icy, hypnopompic places where we can hear Death and other unseen forces calling to us—and maybe even respond to them.

The opening poem, “Preface,” invokes the biblical origins of Genesis, reset in 1960s Poland: a man, a woman, a snake, but also “a stupid apple tree,” “depots, dead buses. / Old lemonade bottles of that unusual shape.” Here are seeds of Świetlicki’s themes: an overpowering sense of menace between sleep and waking, entanglements between the masculine and feminine beyond mere mortals, set among noirish urban landscapes and frosty worlds. The final line, “We’ll be observing the advance of darkness” sets up the reader for the opaque stillness at the heart of winter, questioning what life, if any, remains beneath the cold.

“Everything drips” follows immediately with an imperative, or maybe even a plea: “Don’t come into my dreams, don’t. In one dream / drown for good and don’t show up in any other.” To whom is the speaker addressing? A relative, a lover, a stranger, a monster? The ambiguity of other people’s presences in this poem and others compounds the sense of unease, giving you the sense of a faintly remembered nightmare just out of reach, or a stranger passing by your unlit house. Later on, in “Saturday, an impulse” the speaker announces, “Evil has come to my dream,” after which a female presence instructs them to undress and return to bed where they embrace. Other poems suggest the speaker is themself a dream, conjured by a stone or a stone moon, or a person falls asleep in broad daylight, searching for a missive in the world of sleep. The space between dreamer and reverie is not simply porous or overlapping: it is all-encompassing, cavernous, dissolving into the ache of the unknown.

The female presence in the dreams, waking life, and spaces in between appears to be a lover, the mother of the speaker’s child—or perhaps many lovers, or many mothers—but also an anonymous, distant figure(s) who seems to be on a parallel yet displaced wavelength from the speaker. The speaker seems to be in constant dialogue with this presence and others like it, and even when those energies are absent from the poem’s scene, the speaker continues evoking, recalling, and defying them. Herein is the brilliance of Wójcik-Leese’s translation that melds this shadowy feminine presence with that eternal, ever-present mystery: Death.

One poem in particular showcases the paradox of having a relationship with that mystery. “Posthumous correspondence” (Korespondencja pośmiertna) takes the shape of a stage or screenplay script in which a Man dialogues with Death. Glancing on the left side of the page at the Polish, I observed that the poem followed a different structure, without the character/dialogue formatting.

Curious about this choice, I reached out to Wójcik-Leese, who explained that in Polish, death is grammatically feminine, and so verb endings signifying grammatic gender reveal which passages are spoken by Death and which passages are uttered by the other person. In their translation collaboration, Świetlicki suggested pointing out the different speakers in the exchange, which resulted in a fascinating version of the original poem in English. Both correspondents seem to be speaking aloud (as if in a script), but the framework of the text is as a letter. The reader feels the conflict and contradictions of their communication—not merely between speakers and what they speak of, but how they speak to each other and the plaintive rhythm of their exchange.

Towards the end of the collection, the poems become sparser, more like jottings and diary entries. It’s as if the narrator is integrating the past, musing over the present and future, where “Plastic soldiers utter their war cries” in the ironically titled, “First poem” which is the third to last in the volume. Maybe this is the first poem for a new world or worlds, a transition point for more. It’s significant that Świetlicki has written thirteen books of poetry and that Night truck driver is the first English language collection in his work, which Wójcik-Leese notes in the translator’s afterword “follows the chronology of his poetic life and the lives of his individual volumes.” One hopes that more translations will come, as Świetlicki and Wójcik-Leese capture so hauntingly and precisely the cold ache of being called—and caught—among many worlds.

Radio Interview with Trafika Europe where you can hear Elżbieta Wójcik-Leese read the poems in Polish and English.

Reviewer Amanda L. Andrei is a Filipina Romanian American playwright, literary translator, and teaching artist residing in Los Angeles by way of Virginia/Washington DC. She writes epic, irreverent plays that center the concealed, wounded places of history and societies from the perspectives of diasporic Filipina women, and she translates from Romanian and Filipino to English. For more information on her work and upcoming events, visit: www.AmandaLAndrei.com

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs, as well as our mission to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Theo Angelopoulos – The Landmark UCLA Retrospective

Review by Malina Stefanovska

In the Fall of 2022, the UCLA Film and Television Archive ran a complete retrospective of Theo Angelopoulos, a Greek film director and one of the most famous and beloved filmmakers of South East Europe. The full house of the Billy Wilder theater, the rapt attention of the audience during the many hours of watching, and all the diverse languages spoken around me, made it obvious that his admirers are not only Balkan born, but also a younger generation of film buffs from all over the world. Angelopoulos has won many premier awards, including the Palme d’Or at the Cannes film festival in 1998 for his film Eternity and a Day. Ulysses’ Gaze (1995), won the Grand Jury Prize at Cannes, and Landscape in the Mist (1988) was a winner at the European Film Awards, but it was The Travelling Players—filmed in 1975, during the military junta’s dictatorship in Greece—that established him as a unique voice in cinematography. UCLA’s timely retrospective, titled “Landscapes of Time: The Films of Theo Angelopoulos,” consisted of all the director’s feature films and a selection of shorts. In addition to the films mentioned above, I saw Days of 36, Voyage to Cythera, Alexander the Great, Meadows in the Mist, and The Hunters.

Having seen and loved Ulysses Gaze when it first came out in 1995, while the civil war was still raging in Yugoslavia, I wanted to see some other Angelopoulos’s films. They are so intimately intertwined with our Balkan history that I was ready to immerse myself in an experience that I knew might be unsettling and unforgettable.

I got more than I expected! I spent many hours in utter nostalgia for my Balkan roots, and the torn, conflicted, and stunning world poetically depicted in his films. It was inevitable that I completely surrendered to Angelopoulos’ meditations on history, reliving or imagining it with all my senses: images, music, the slow passing of time, the long shots of Macedonian villages in winter, the feeling of being part of a community, the exile and oblivion that engulfs it all sevdah, this feeling of sadness for what we have left behind, is the Balkan’s heritage from our common Ottoman past, the Eastern equivalent of the Portuguese saudade.

It is a sadness cultivated through beloved musical traditions, and glorified in poetry and cinematography. In a film modeled after Zorba the Greek, such longing would have been represented by drinking, listening to musicians, and breaking dishes, in a sort of communal catharsis.

None of that gesturing was present in Angelopoulos’ films, and I did not miss the expression of feelings in such demonstrative ways. Yet, as a typical daughter of the Balkan South, I was completely immersed in each of his films, gripped and torn by histories so closely intertwined with my own: my family, from what is now officially North Macedonia, came from both sides of the border; my father fought alongside Greek partisans in World War II, and even learned the language from them; the Manaki brothers (in Greek, Manakis)—whose disappeared reels of film are chased throughout several countries by the hero of Ulysses’ Gaze—lived in Bitola, my family’s hometown, and they were my grandfather’s friends. They both belonged to that Hellenophile ethnic minority, the Vlachs, that once created the city’s culture and is slowly disappearing.

Both on screen and in the audience, I heard long forgotten Greek words from my childhood, and—miraculously—I understood them. Even the recordings of village life by the Manaki brothers, shown in the film, brought back memories of my peasant grandmother teaching me how to spin wool. The bombing of Sarajevo, another beloved city of my youth, made me howl like the protagonist of Ulysses’ Gaze (top image), played by Harvey Keitel.

Needless to say, all the music, from the soulful rebetika to the peasant Macedonian music played by my grandfather, was equally and painfully close to my heart. Even my son’s name, Theodor, chosen in homage to my roots, brought me closer to Angelopoulos! It was as if he spoke exclusively to me, a viewer uniquely familiar with his world.

But then, in the rapt silence of the audience, I realized that something much larger than my own perspective and past connected us all. It was Angelopoulos’s unique cinematography and his understanding of history. This was evident by the audience never saying a word, never leaving before films ended (not even for the Travelling Players, which is over four hours long), in the enthusiastic applause after each show, and in the heartfelt and beautiful opening words delivered by UCLA’s head archivist Paul Malcolm and by Ioannis Stamatekos, the Consul General of Greece in Los Angeles, and Sharon E. J. Gerstel, director of the UCLA Stavros Niarchos Foundation Center for the Study of Hellenic Culture.

Theo Angelopoulos has become known as one of the most important filmmakers of the twentieth century. His career spanned from the early 1970s to 2012, when his last film was brought to a standstill by his tragic death during shooting. He was admired by such auteurs as Bernardo Bertolucci and Wim Wenders for his characteristic style: He used slow, ambiguous, overlapping narrative structures and long takes which often included meticulously choreographed scenes and many actors (The Travelling Players consists of only 80 shots in over four hours of film). He also championed a radical Brechtian point of view where the actors at times broke the fourth wall to deliver their narrative directly to the audience.

Most of Angelopoulos’s films are shot on the northern border of Greece, in rainy and snowy winter weather, in remote mountain villages. He preferred a dark palette of colors diametrically opposing the usual “tourist-sunny” representation of that country. I came to recognize a few recurring visual tropes: rafts or boats slowly gliding away on a river, a snowed-in mountain village, a long frontal take of a group walking up a slope, a conspiratorial whistle of insurgents that carried across the mountainous landscape. These epic and allegorical meaning are always present, to be interpreted at many levels, akin to a myth.

Angelopoulos’s films are as steeped in mythology as they are in recent Greek history or his own personal quest. In Ulysses’ Gaze, the four different women (played by a single actress, Maia Morgenstern), stand for Penelope, Calypso, Circe and Nausicaa, while its hero—a filmmaker named only “A”—is both Odysseus and a stand-in for Angelopoulos as “auteur.” The Travelling Players retells Aeschylus’s Oresteia, with characters ranging from Orestes and Pylades to Electra, Agamemnon, Clytemnestra and Iphigenia replicating the antique tragedies. The fusion and clash between myth and history is in itself the subject of Megalexander, the story of an early twentieth-century insurgent bandit who saw himself as Alexander the Great. What a pity that Angelopoulos did not live to see Alexander’s latest avatar revived, mythologized and re-appropriated as “Aleksandar Makedonski” in the newly-independent (and heavily politicized) State of North Macedonia!

But the main way in which Angelopoulos’ films touched me is not the retelling of myths, as rich as they can be. It is the more recent Greek and Balkan history, and his poetic and complex rendering of our connection with History at large. Some critics have said that “no one but a Greek can understand all the political, historical and mythic allusions.” This might be true, but the main tenets of Angelopoulos’s perspective remain excruciatingly clear.

The civil wars in Greece and some of its Balkan neighbors have taken most of the twentieth century in fits and starts. Fostered in large part by British and American imperialistic agendas and meddling (though swiftly forgotten by the West), these conflicts have been largely erased from the official historical memory of Greece. Yet they remain a submerged component of the proverbial popular pessimism in the region.

Both in The Hunters and The Travelling Players make this obvious in the constant juxtaposition between the 1936-39 civil war, the Second World War, and the civil war of 1947-52 which brought about Greece’s military junta. The unfinished search for a disappeared or fading past is in itself the principal theme of Ulysses’ Gaze. That quest is symbolized by Golpho, a popular pastoral played by itinerant players, that starts over and over but is repeatedly stalled by the interference of historical events. As a play that never ends, its allegorical meaning is clear. So is Angelopoulos’s haunting odyssey, Landscape in the Mist (1988), where the story told by an adolescent girl (named Voula, after the director’s sister) to her younger brother Alexander only provokes his complaint: “This story will never get finished.”

This innocent observation appropriately characterizes Angelopoulos’ cinema. From the absence of the conventional word “End” at the conclusion of his films, to his truly unfinished last one, to his penchant for interweaving variations of his personal history or episodes from earlier films into later ones, he creates a continuous, unfinished work. It is both intimately autobiographical and allegorical. Like the children in Landscape in the Mist, Angelopoulos’s films allow their audiences to cross into a space where the real and mythic intersect to map Greek and Balkan history.

Malina Stefanovska is a professor in the Department of European Languages & Transcultural Studies at UCLA

Originating from a multilingual and multicultural background in ex-Yugoslavia, Malina Stefanovska was educated on three continents: Africa, Europe, and America. She holds a B.A. from Grenoble via Université de Brazzaville, an M.A. from the University of Oregon, and a Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins University.

Professor Stefanovska also worked as an interpreter and translator for French, English, and Serbian, studied Spanish out of love, and wrote and translated literary texts and poetry in several languages. After completing her doctoral thesis on Saint-Simon, which was published as a book in France, Malina further specialized in memoir authors and autobiographical writings of Early Modern France, as well as their modern forms, from the narrative to the visual, from the fictionalized to “auto-fiction” or journal.

She is also a practicing autobiographer and recently completed a manuscript about a Macedonian childhood and family history. Her next project, related to passions and emotions in 17th and 18th century France, will consist in a study of Casanova, written in the form of letters to this author by a reader who admires him.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs, as well as our mission to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Review: And If I Don’t Behave Then What

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

Open Fist Theatre Company

Through March 4

And If I Don’t Behave Then What

L.A. premiere of the new play by Iva Brdar

Ovaries on the concrete. Chin and cheek dimples with the sound of a drill. Being polite, kind, and well-behaved in the face of nameless, insidious forces.

The play consists of various vignettes, starting from Age 0 and culminating when “Woman” is in her 70s. Woman consists of Cynthia Ettinger, reading pages of printed paper or from her phone as she recounts memorable events of a life. However, Woman also consists of Carmella Jenkins, who could be interpreted as a version of a younger self, or another part of the subconscious, and at times Debba Rofheart, the most prominent candidate for the Woman’s mother, voicing the mother’s instructions to her daughter (such as the darkly humorous line, “Don’t sit on concrete, your ovaries will get cold”). And Woman could also consist of Howard Leder, playing the majority of the men’s roles, where the masculine in this world is coldly distant, silent in its brutality, or in a deadpan delivery drawing amusement from the audience, hilarious in its unawareness in giving instructions on how to parallel park.

Photo by frank ishman

All these scenes seem to add up to a life that, while portrayed intimately in its details, still feels alienated in the world and to the audience. Rofheart’s “character” (if you can label that part of the text as such) never moves from the seat at the darkened desk, casting a metaphorical shadow of an ever-present yet never-interacted-with mother. And Ettinger has a lovely, soothing voice—when glancing away from the pages, she also serves us lively facial expressions and reactions.

Yet I found myself craving more from the text and questioning the choice to leave the Woman character seemingly on book. Is the Woman a writer or otherwise an intellectual? Is the story so burdensome that it needs an additional interface of pages to separate us from the pain at the heart of these vignettes? From a literary standpoint, these words and images are beautiful, but seeing it performed, I found myself living in my head, the words washing over me, wondering about who the person was behind the text.

And that may be part of the intended effect. I also found myself yearning for more grounding from the playwright’s culture, simultaneously questioning if this world was meant to be a more anonymous post-communist country. The text referenced a former communist country and teaching Marxism, but that could be so much of not only Eastern Europe, but Asia or Latin America as well. I wondered if, from a translation standpoint, there were more words from the original language that could culturally ground the text, or if from a design point, more references to the original culture of the text and its author could be included in the musical transitions or projections—not to exotify, but more to ground an audience member.

Or perhaps that is part of the whole point, that even if the playwright is identified as Serbian, the region has dealt with such a variety of labels, conflict, and grief that perhaps the priority of this performance is not culture, but rather womanhood, the multiplicity of a woman’s life, and the entanglement between mother, daughter, and other knotted ancestral ties and norms packaged up as folk culture to keep us safe. Furthermore, Director Beth F. Milles notes in the program that the piece is written as a “long tone poem” with no punctuation, and so the possibilities for this text are immense. And perhaps this immense tension is what ultimately underlies the piece—that while there are so many possibilities in life, it might still end in a strangely alluring yet alienating mystery.

Atwater Village Theatre is located at 3269 Casitas Ave in Los Angeles, CA 90039. Parking is free is in the ATX (Atwater Crossing) parking lot one block south of the theater.

To purchase tickets and for more information call (323) 882-6912 or go to www.openfist.org.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs, as well as our mission to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

The Frontier Café – Conversation with Ines Tanović

The history and future of Balkan Cinema

Please subscribe to our new podcast. Available on Anchor, Spotify, Amazon Music, Google Podcast, Castbox, Pocket Cast, Radio Public, YouTube

This episode of Frontier Cafe features a conversation with Ines Tanović, the manager of the production company DOKUMENT and the Sarajevo Film Center. The conversation, in Serbo-Croatian, went over her career as a filmmaker, the history of Yugoslav cinema, and her current efforts to promote local Balkan film cultures and auteurs.

Note: This interview is in the Bosnian language (download the English translation here).

About the Guest

Born in Sarajevo in 1965, Ines Tanović graduated at the Dramaturgy Department of the Sarajevo Academy of Performing Arts. She has been a member of the Association of Filmmakers of BiH since 1988. In 1991, with her father, Sejfudin Tanović, she founded a production called DOKUMENT in Sarajevo, which is now managed by her and Alem Babić, a producer. From 2014 to 2019, she was the president of the Association of Filmmakers of the FBiH and of the Association of Filmmakers of BiH. She is currently holding a position of acting general manager of the Sarajevo Film Centre. From 1986 to 2002, she wrote scripts and directed 6 short fiction movies. She worked as an editor at national and federal public broadcasting stations. In 2004, she was awarded by the Hubert Bals Fund for the script for “Entanglement”. She attended the Berlinale Talent Campus 2006 and her project “Decision” was selected among 160 entries from all over the world, for Berlin Today Award 2011.

In 2010, she directed the Bosnian part of the long feature omnibus “Some Other Stories” (coproduced by BiH, Serbia, North Macedonia, Slovenia, Croatia, and Ireland, supported by EURIMAGES). The film has been invited to more than 40 international festivals and earned six international awards. She is the author of a short film titled “Starting Over”, screened in the short film competition section of the 16th Sarajevo Film Festival in 2010. The film has been shown at many international festivals. Her film “Our Everyday Life” has been shown at more than 45 international film festivals and has earned 15 awards. The film was selected as a Bosnian and Herzegovinian entry for the 2015 Academy Awards.

She is the author of documentaries titled “Exhibition” (shown at the SHORT CORNER of the 2009 Cannes festival), “Living Monument” (2012), “Coal Mine” (2012), “Ghetto 59” (2013), and “A Day on the Drina” (2011), which was rewarded with the Big Stamp Award for Best Film of the 2012 ZagrebDox International Documentary Film Festival, and it was screened as a competing documentary at the 2012 Sarajevo Film Festival. Her second film “Son” premiered in the Competition Program – Feature Film at the 25th Sarajevo Film Festival (2019). The script for this film was awarded as the best project of the 2015 CineLink, and the most promising European project, as voted by LA producers, at the 2016 SEEfest LA. It has been screened at numerous international festivals.

Connect with Ines Tanović on Social Media

Instagram | Facebook | Twitter

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs, as well as our mission to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!