ROMANIAN TIFF AND CZECH KARLOVY VARY HEAT UP THE FESTIVAL SUMMER

It’s Film Festival Season in South East Europe!

The busy festival summer kicks off this weekend with the 24th annual Transilvania International Film Festival in Cluj-Napoca, Romania, followed in July by the 59th festival in Karlovy Vary, Czech Republic, and the 72nd Pula Film Festival in Croatia.

Next in August are Locarno (the 78th edition) and Sarajevo (the 31st), the largest regional festival in South East Europe.

And there’s more to explore on the festival circuit! Packed programs with an increasing number of sidebars, industry platforms and special cultural events offer festivalgoers plenty to choose from.

Whether you’re a film industry insider or a tourist, European festival summer is welcoming to all guests. Enjoy!

TIFF Romania – https://tiff.ro/en

Karlovy Vary – https://www.kviff.com/en/homepage

Pula – https://pulafilmfestival.hr/?lang=en

Locarno – https://www.locarnofestival.ch/home.html

Sarajevo – https://www.sff.ba/en

“Greek Apricots” at Future Frames in Karlovy Vary

Short film by Slovenian director Jan Krevatin, “Greek Apricots” – which L.A. audiences saw at SEEfest in May, is part of European Film Promotion’s program Future Frames at the upcoming Karlovy Vary International Film Festival, July 4 – 12.

The film portrays a couple brought together by their shared Macedonian roots on a quiet summer night, and features renowned N. Macedonian actress Labina Mitevska (“Before the rain,” “I am from Titov Veles”). Congrats to the young filmmaker!

…and a few books to read on long summer nights…

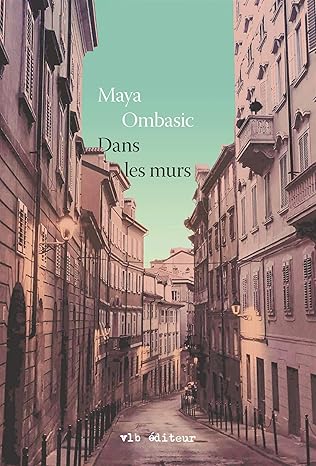

Maya Ombasic, from Bosnia and Herzegovina and based in Quebec, Canada, whose breakout debut “Mostarghia” established her on the international literary scene, has several books in print albeit mostly in French.

“Lejla” (Dans les murs) features a woman traveling to Trieste, a city she’s fascinated by since childhood, and a city that encapsulates the unique milieu of Central/East and Southeast Europe.

And More:

Andrey Kurkov, Ukrainian author whose novel “The Silver Bone,” translated by Boris Dralyuk, was on the 2024 International Booker Prize longlist.

Georgi Gospodinov: The Bulgarian author, who won the 2023 International Booker Prize with “Time Shelter,” translated by Angela Rodel.

Jenny Erpenbeck, a German author from the former East Germany, won the 2024 International Booker Prize for “Kairos,” translated by Michael Hofmann. This novel is set in the final years of communist East Germany.

“This Way to Paradise – Dancing on the tables,” a book about life in Greece, by lifelong Philhellene (and a supporter of SEEfest since its early days,) Willard Manus.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Review: Anora

Reviewed by Aleksandr Tverdokhleb

Warning: Contains spoilers for Anora

Weeks have passed since the 2025 Academy Awards ceremony, which took place on March 2 at the Dolby Theatre in Los Angeles. The film Anora by Sean Baker was the evening’s triumph, winning five statuettes out of six nominations, making it the most awarded film at the event. The movie tells the story of Annie Mikheeva (played by Mikey Madison, who won an Oscar for this role), a prostitute and daughter of Russian-speaking immigrants. While working at a strip club, she meets Ivan (Mark Eidelstein), the son of Russian oligarchs. He offers her money to live together, later confesses his love, and proposes to her despite the radical disapproval of his parents (Aleksei Serebryakov and Darya Ekamasova, respectively).

Even if you haven’t heard about Anora before, its cast alone highlights its uniqueness: among the lead actors, only Mikey Madison is American; the other key characters are played by four Russian actors and two Armenian-born performers. This gives the film a distinctive atmosphere, reflected not only in the script (a quarter of the dialogue is in Russian) but also in its rich Eastern European aesthetic. This is evident not only in the characters’ costumes, which differ significantly from the American crowd, but also in certain small habits that are very familiar to Eastern European residents. For example, at one point in a cafe, Toros (Karen Karagulian) starts scolding the nearby American youth, using extremely stereotypical phrases about how the new generation is “not what it used to be” and “doesn’t respect their elders,” even though the American kids have done almost nothing. I think this is very familiar to those who grew up in Eastern Europe and often faced judgment from older generations in public places, hearing similar phrases—even when they had done nothing at all. It’s also noticeable that the Armenian characters park terribly every time, breaking multiple rules and even getting fined once, which feels completely natural, given that they come from a country that is significantly less car-oriented than the U.S.

At first glance, the film seems to follow the signature style of Sean Baker’s directing. His previous works—Tangerine, The Florida Project, and Red Rocket—focus on marginalized communities, with the protagonists of Tangerine and Red Rocket also tied to the adult entertainment industry. However, Anora takes a slightly different path:within the first 20 minutes of the film, the heroine finds herself in a world of luxurious interiors and ultra-wealthy elites.One of the film’s standout features is its visual style, which earned an Oscar for Best Editing. Baker has always been known for his experimental approach to cinematography—for example, Tangerine was shot on a modified iPhone camera to enhance realism. In Anora, he employs various unique cinematographic techniques. In an interview with Hammer To Nail, the director revealed that he deliberately changed film stock and lenses to emphasize color contrasts, with warm tones giving way to cold ones, creating a visual transition between different worlds. Additionally, this helped evoke a 1970s aesthetic, with the set design carefully chosen to match this effect.

eight films, he was the director, screenwriter, producer,

and editor.

Anora has a distinct, three-part structure. The first part is an erotic melodrama centered on the relationship between Annie and Ivan. This is the weakest segment of the film. The second is a burlesque comedy that begins with the arrival of Armenian “bodyguards” (Karen Karagulian and Vache Tovmasyan) and the Russian “bouncer” Igor (played by Oscar nominee for Best Supporting Actor, Yuri Borisov), whom Ivan’s parents send to New York to annul his marriage to Annie. The third part is a drama, though not without humorous moments—Baker generally avoids pure drama, preferring to balance intense scenes with irony. All three parts share a similar narrative structure, featuring abrupt transitions from loud scenes where characters shout at each other, to quiet episodes in which they sluggishly chew food, watch TV, or engage in routine activities with almost no dialogue.

Overall, the film flips the classic Cinderella storyline on its head. We’ve seen this before in the 1990 film Pretty Woman: a young woman from the social bottom falls in love with a wealthy man and enters the world of the rich. But instead of happiness, as in traditional fairy tales, she discovers that her chosen lover or suitor—who has only known her for a couple of weeks—does not truly love her. And both protagonists of these two Cinderella-esque films realize that money is not a cure-all for life’s problems.

In 2025, viewers of Anora already understand the unrealistic nature of tales like Cinderella and may not expect a happy ending for Anie and Ivan’s relationship. It doesn’t help that Ivan is portrayed throughout the film as an infantile,thoughtless teenager. However, the goal of the film is not to surprise the audience with the sudden realization that marrying someone after two weeks, especially when that person behaves like a child, is a bad idea. Instead, Sean Baker’s aim is to highlight the doomed nature of this marriage via the characters who become the emotional core in the second half of the film: the Armenian “fixers” Toros (Karen Karagulian) and Garnik (Vache Tovmasyan), as well as the Russian Igor (Yura Borisov). These latter characters have incredible charisma. Given that a large portion of their dialogue was improvised, the actors demonstrate remarkable skill. Sean Baker does not speak Russian, so the delivery of lines relied entirely on the actors themselves. The choice of words and intonations was up to them, and in this regard, all Russian-speaking characters showcase an exceptional level of acting.

So what is Anora really about? Neither Ivan nor Anie evokes strong positive emotions at the beginning of the story—one is an immature fool, and the other is overly trusting and at times overly hysterical. Watching the first third of the film, as a viewer, you want to tell Anie not to be so naive when Ivan repeatedly proves how irresponsible he is. And you also want to tell Ivan that to stop acting like a child. When the characters played by Vache Tovmasyan, Yura Borisov, and Karen Karagulian appear, they do exactly that—they voice the concerns of the audience, and interfere with the romance. This strengthens the viewers’ emotional connection with them. On top of that, they deliver almost all of the film’s best jokes. Even when reading American reviews of the movie (for example, on IMDb), it’s clear that even those who didn’t like the film still appreciated the outstanding performances of the Russian-speaking actors.Anora does not just tell the story of Mikey Madison’s heroine—it also presents a classic Hollywood narrative through the eyes of people who usually remain in the background: the employees of wealthy Russian oligarchs, who may appear to have no “real” influence and who work for extremely unpleasant individuals, but still try to conduct themselves with dignity. These characters may be easier to relate to, for the audience

Karen Karagulian, Mikey Madison, Yura Borisov, and

Vache Tovmasyan

Anora is not without its flaws. The excessively sharp editing and the alternating loud and silent scenes may feel exhausting. Additionally, in the first third of the film, the main characters can be irritating at times. However, these shortcomings pale in comparison to the film’s strengths, and Sean Baker absolutely deserved those Oscars.

As for the actors from Southeastern Europe, they deserve the applause too. They not only delivered phenomenal performances, but also became the emotional heart of the film. Thanks to them, Anora stands out from the sea of films released in the past year, serving as a brilliant example of how Russian language and Russian-speaking actors can be used in cinema in a way that feels natural, effective, and well-done. It is especially gratifying to see that Western audiences have also appreciated these performances, confirming just how exceptional they truly are.

Aleksandr Tverdokhleb is a student at Pomona College who is studying cognitive science. He reviews films that reveal how members of one culture perceive and interpret a culture less familiar to them. Additionally, he enjoys exploring the phenomenon of Eastern European diasporas in the United States.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Review: “Bounds” and “I Want a Country”

| Location | 2525 Michigan Ave., Building T1, Santa Monica, CA 90404 |

| Theater | City Garage at Bergamot Station |

| Date of Performance | February 7, 2025 and February 9, 2025 |

| Language(s) | English (translated from Italian and Greek, respectively) |

| Photos by | Paul M. Rubenstein |

Reviewed by Allie Rigby

Where do you go when your country has dissolved or fallen apart? What opportunities and purgatories await displaced people who have risked everything for a chance at a better life?

This weekend, two plays opened at City Garage Theatre, both with painfully relevant themes exploring what it means to leave one country forever–or consider leaving it–only to land in a disorienting, dangerous place where arriving becomes an impossible feat.

In this production of Bounds by playwright Tino Caspanello from Italy, and translated by Haun Saussy, five women in matching black outfits command the stage, collectively passing the time on the beach with conversation, dancing, fights, and childlike games with high stakes. The play opens with Woman 1 (Lenka Janischova Shockley) kneeling center stage, wishing for the comfort of a chair, which we later learn she does not have because she lost the most recent round of musical chairs.

Shockley delivers in this role, with her character often challenging the social hierarchy established in this liminal place, with its pecking order led by Woman A (Angela Beyer), and loosely reaffirmed by Woman C (Devin Davis-Lorton) and Woman B (Alyssa Frey). Meanwhile, Woman 2 (Alyssa Ross) seems aware that like Woman 1, her status among the group is not secure, and she may be the one sent back home.

Janischova Shockley, and Alyssa Frey. Photo credit:

Paul M. Rubenstein.

Rules keep the group in some order and also help pass the time. By the end of the play, it remains unclear who will be sent back home, or if any of them will be allowed to enter this new country. All we know is that they are tired and they have been waiting for a long time to arrive.

Directed by Frédérique Michel and produced by Charles A. Duncombe, Bounds succeeds in conveying the uncertainty and fear that the five displaced women share, despite their differences in personality, status, dreams, and beliefs. Duncombe also achieves an uncertain, ominous atmosphere with his choice of rumbling, surveillance-type sounds (ie., helicopters hovering) that grow especially loud in the final scene, where these women await their fate in this new country.

The ending in I Want a Country is similar in that it is also ambiguous, but in a way that is more satisfying because the characters never left their “dead” country to begin with. The despondent, anticlimactic ending conveys the hopelessness of staying in a country where life has been sucked out of it. Written by playwright Andreas Flourakis from Greece during the financial crisis of 2010, and translated by Eleni Drivas, I Want a Country conveys the impossibility of shaping a new nation by consensus or democracy.

Duncan, Alyssa Ross, Liam Galaz Howard, Shane Weikel,

Angela Beyer. Front: Daniel Strausman, Alyssa Frey, Angela

Beyer. Photo credit: Paul M. Rubenstein.

Throughout the play (also directed by Frédérique Michel and produced by Charles A. Duncombe), characters pop umbrellas to weather storms, support their partner, and carry on, but they cannot agree on much, including where to go, how a country should operate, who to welcome, who to exclude, how to make and share money, etc. A lack of money and lack of imagination are part of the problem:, the group struggles to describe a new, ideal country that does not reproduce the same ills they seek to flee.

Director Frédérique Michel adds gorgeous moments of pause, where characters freeze while doing menial tasks like tying their shoes or walking arm in arm. These glitchy, staccato moments, coupled with sequences when the characters walk backward rather than forwards, solidify a place where time is slightly warped and characters are stuck with indecision around where to go and how to make the next place better. Duncombe’s use of a didgeridoo as part of the sonic atmosphere adds a heavy, pulsating layer to these sequences where the characters are stuck in limbo.

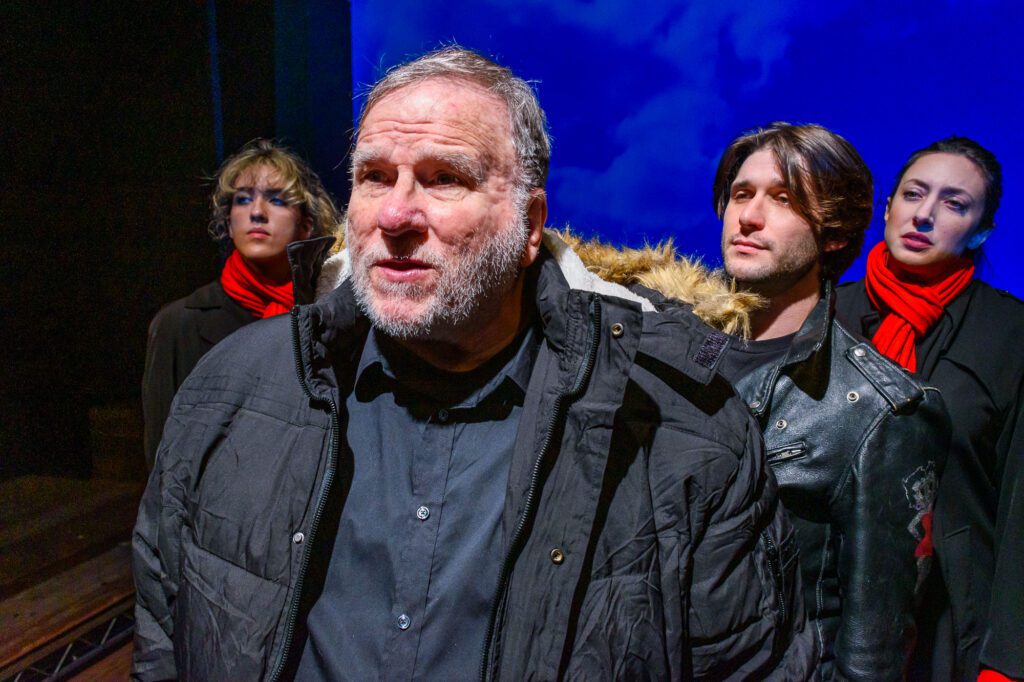

Perhaps most memorable is Papa Escargot (Andy Kallok) whose feelings of hopelessness are palpable beginning from the moment he enters the stage, stumbles upon a pair of discarded shoes, and slumps over, exhausted, sitting on his suitcase.

Photo credit: Paul M. Rubenstein.

There are also fantastic lines throughout, such as when Storm (Daniel Strausman) gets frustrated at the group’s return to money as the solution to all their problems, saying:

STORM: “Come on guys, we’re talking about doing something revolutionary, and again the conversation goes back to money.”

TOMY: “It’s hard not to.”

LONELY: “Force of habit.”

TOMY: “We don’t just need a new country — we need a new way of thinking.”

This new way of thinking may still be what we need here in the United States too. Both of these plays are timely, especially amidst the rising threats of mass deportations of immigrants, unreasonable searches and incarcerations, and increasingly militarized borders.

Once again, and per their thirty-five year record, City Garage Theatre has produced plays that speak to the times and encourage people to have empathy and compassion for what it means to arrive in a country that may pummel you into the ground.

As Woman 1 says in Bounds,

“This whole thing is . . . inhuman.”

The plays will run in repertory, with Bounds Thursdays and Fridays, and I Want a Country on Saturdays and Sundays until March 16.

Allie Rigby is a poet, editor, and reviewer with roots in Orange County, California. She is the author of Moonscape for a Child (Bored Wolves, 2024) and the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship to Romania, where she taught creative writing at Universitatea Ovidius din Constanța. She holds a master’s degree in English: Creative Writing from San Francisco State University. She enjoys connecting with people to develop and share stories that generate cross-cultural dialogue, solidarity, and change. For more of her work and upcoming events, visit www.allierigby.com or @allie.j.rigby.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Review: The Seagull

| Location | 2055 S Sepulveda Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90025 |

| Theater | The Odyssey Theatre, Los Angeles |

| Date of Performance | January 18, 2025 |

| Language(s) | English (translated from Russian) |

| Photos by | Sasha Dawson and Miguel Perez |

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

“We need new forms,” declares Konstantin Treplev, a fledgling playwright and son of an aging actress, of the theatre. “New forms are needed, and if we can’t have them, then we had better have nothing at all.” It’s also through old forms, such as Anton Chekov’s comedy The Seagull, that audience members can contemplate the role of artists and the snares of love. Although Odyssey Theatre Ensemble’s vision of this play contains stylistic twists which belie Chekov’s realism and create an undercurrent of dissonance, the poised portrayals of the iconic Boris Trigorin and Irina Arkadina bolster the tragicomedy.

Dramatist and author Anton Chekov penned The Seagull 130 years ago, with its premiere a year later, in 1896 at the Alexandrinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, Russia. Set in a lake house and estate in the Russian countryside in the same era, the play served as an opportunity for the turn-of-the-century audiences to see themselves reflected in stark, realistic terms: family dynamics, class differences, and love triangles during a shimmery summer and then two years later, in a thunderstorm.

There’s Irina Arkadina (Sasha Alexander), a theatre actress trying to reclaim her youth and influence, visiting her brother Pyotr Sorin (Joe Hulser), retired official and owner of the lake house. Her son Konstantin (Parker Sack), living under the shadow of his mother and aspiring to be a writer. Boris Trigorin (James Tupper), established writer and paramour of Irina, who falls for the 19-year-old idealistic Nina Zarechnaya (Cece Kelly), a neighbor to the estate who longs to be an actress and in the world of theatre and literati. And then there are multiple other guests, neighbors, and servants who add to the rich texture and intrigue of Russian society.

It would be easy to paint Trigorin as a slimy creep, preying on a teenage Nina for his own base desires and insecurities. But James Tupper is exquisite, inhabiting the role with such innocent presence and care that it’s easy to be seduced by—and sympathetic towards—this romantic writer. Sasha Alexander also fills her Irina with vigor and desperation, drawing bursts of laughter with her comedic timing and commanding rapt attention as she baits Trigorin to return to her arms. Parker Sack as Konstantin offers boyish rebellion, optimism, and moodiness—he shines best during a verbal throwdown with his rapacious mother—though witnessing a more transformative arc towards the end would have been more satisfying and poignant. Performances by Will Dixon as Dr. Dorn, and Carlos Carrasco as the steward Shamrayev, are also notable for the gusto and enthusiasm they bring to these side characters.

by the lake. Photo credit: Miguel Perez.

Part of the trouble with this production is that some of the visual stylistic choices conflict with the realism and era invoked from the text, a translation from 1960 by Ann Dunnigan. The translation itself is clear, and occasionally feels dated with its exclamations and endearments (“Fiddlesticks!” “Little one!”), but the dated feeling seems to come more from the ambiguity around time and place within the production. It’s unclear what the time period is: costumes and props verge on the modern, and small details like sunglasses, a camouflage outfit, and a ballpoint pen impart anachronistic touches that distract. The sprawling moss and large aquamarine lake in the background (cleverly designed by Carlo Maghirang) evoke feelings of immersivity and stagnancy beneath beauty, but also give an expressionistic feeling, as if the house and action symbolically live within the lake, instead of alongside it.

Director Bruce Katzman also crafts some moments of characters freezing in charged moments, creating silent tableaus that adds a touch of strangeness to the production. The choice to get playful and more abstract with The Seagull is a noteworthy one, though it seems the production would benefit from a more modern or updated translation that would allow the creative team to be more flexible with the contemporary design choices and have a more unified vision.

Given the situation with the wildfires, it can be jarring to return to the theatres during this time in L.A. Chekov’s summer vacation world and love entanglements seem far removed from the disaster befalling the City of Angels. But in fact, they hearken to L.A. as the illusory La-la-land, that amidst the luster of the entertainment industry, there are scores of individuals who are dreaming, scheming, and hustling to make a life in the arts. Some motives may be naïve or petty, others heartfelt and sincere.

As Nina tells Konstantin towards the end, after her share of trials and heartbreak,

“I know now, I understand, that in our work, Kostya—whether it’s acting or writing—what’s important is not fame, not glory, not things I used to dream of, but the ability to endure.”

In this time, that endurance is a reminder for every Angeleno.

Cristina Sandu Bio: Journalist Cristina-Ioana Sandu graduated from De Montfort University in the UK and is passionate about photography, cinema, music, and storytelling. With a background rooted in journalism and media, Cristina brings a vibrant perspective to her work, shaped by hands-on experience in the film industry and live event production.

Her journey also includes crafting compelling narratives that explore identity, art, and human connection. Her blog acts as a personal and creative space to document life, celebrate authenticity, and highlight significant voices in arts and culture. Discover more at: www.cristinaioanasandu.com

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Review: First Light by Zafer Şenocak

| Author | Zafer Şenocak |

| Translated By | Kristin Dickinson |

| Genre | Poetry |

| Language(s) | Turkish, English |

| Format | 160 Pages |

| Publisher | Zephyr Press |

| ISBN | 978-1-938890-30-7 |

Reviewed by Allie Rigby

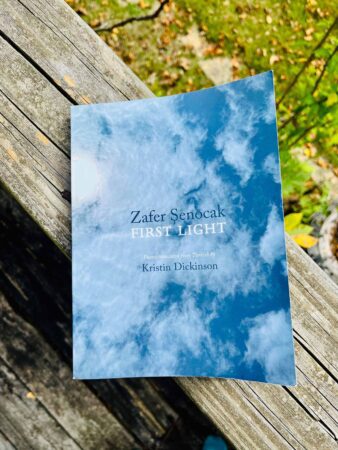

What does it mean to exist in one place, physically, but mentally and emotionally exist elsewhere, simultaneously suspended in past, present, and future? Such time-warped entanglement ricochets throughout Zafer Şenocak’s bilingual poetry collection, First Light, translated from Turkish into English by Kristin Dickinson (Zephyr Press, 2024).

Many of the poems speak to the ideas of memory, language, and home, home being an ethereal concept often–if not ever so slightly–out of reach; accessible in wisps, dreams, and impressions that linger as briefly as morning light.

Şenocak’s poems ache with longing and acknowledgments of human contradictions. The original poem unfolds on the left page, in Turkish, and on the right lays the English translation.

In the poem, Muammaydun or I was a riddle (pg. 68-69), the speaker’s voice aches with loneliness and the universal desire to be known:

“I didn’t want to be an I

I wanted there to be someone

Yearning for me

My faithful companion

When you reach me

Let me be known” (Lines 16-21).

The “you” is an especially compelling address in this poem and throughout the collection. Is “you” a lover? The reader? A deeper, spiritual companion? The “cosmos” as Dickinson writes in the opening text “Unraveling the Self in Translation”? All of the above? With the “you” address, readers are brought into an intimate conversation between the speaker and someone. How readers interpret the “you” will influence each subsequent reading of the poem. But rather than get too stuck on who this “you” may be, I ask myself what the poet Brynn Saito encourages her students to ask themselves, when reading a poem for the first few times: how does the poem make me feel?

After reading I was a riddle I initially felt soothed by the longings I shared with the speaker; I also felt forlorn that loneliness was so inevitable. The repetition of “I” in Line 16 has a sense of contraction in itself–only through the “I” can the speaker express who they do and don’t want to be, and how to break free of the loneliness of the singular “I” is simultaneously impossible and desired.

The last two lines provide the solace, the hope, that someone, or something, will enter the speaker’s life and see them truly. Does this happen at death? Or before, via spiritual companionship? Or perhaps with deep friendship? Like many poets whose writing I admire, Şenocak does not answer it explicitly, but rather, lets us revel–and struggle–with the questions.

It’s impossible to ignore the role of language in any work of translation. Those who are familiar with Şenocak’s impressive canon of work, which according to his bio on Zephyr Press, includes “ten books of poetry, seven novels, and five essay collections” may know that he wrote much of his earlier work in German first, rather than in Turkish. Zephyr Press published Door Languages in 2008, which Şenocak wrote in German and Elizabeth Oehlkers Wright translated into English. First Light was written in Turkish first, as is much of Şenocak’s recent work. Translation is an art and an interpretation, the initial language of a text will influence the subsequent translations.

The relationship between language and home is deeply intertwined in this collection. In Kalbini üzme or Don’t trouble your heart (pg. 30-31), the poem flows from the title as:

“May the dust surrounding it

Never tire you

Neither home nor homesickness will come of that dust

You’ve tried enough

To make a home at the water’s edge” (Lines 1-5).

What troubles the speaker here is not the inevitability that dust falls around the heart, but rather the exhaustion that comes from this dust. There is a gentle acceptance in this address, an invitation to imagine a different kind of home: whatever actions the addressed “you” has made to make a home have not succeeded. The rich image of making a home at the water’s edge is once again soothing and promising, and yet, the speaker here reminds the “you” that they can pause that home-making attempt.

What then, does it mean, to forgo making a home? Or is home not a physical thing to make, but only possible in the form of language, itself? To be at home in language.

To–as Şenocak closes that poem–“Let the knots in your throat open.” Each poem then, an experiment into untying more of the ropes that bind us.

Allie Rigby is a poet, editor, and reviewer with roots in Orange County, California. She is the author of Moonscape for a Child (Bored Wolves, 2024) and the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship to Romania, where she taught creative writing at Universitatea Ovidius din Constanța. She holds a master’s degree in English: Creative Writing from San Francisco State University. She enjoys connecting with people to develop and share stories that generate cross-cultural dialogue, solidarity, and change. For more of her work and upcoming events, visit www.allierigby.com or @allie.j.rigby.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Review: God of Carnage

| Location | 905 Cole Theatre @ Anthony Meindl’s Actor Workshop – 905 Cole Ave, Los Angeles, CA 90038 |

| Theater | Thunderbird Garage Productions, Los Angeles |

| Date of Performance | September 15, 2024 |

| Language(s) | English (translated from French) |

| Photos by | Zadran Wali |

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

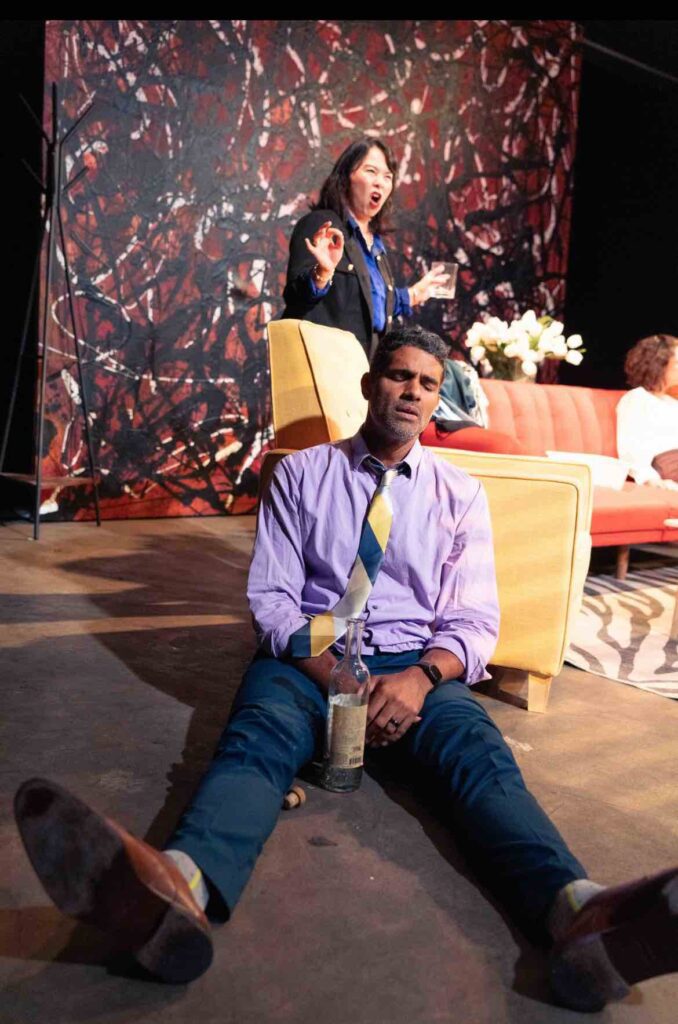

Ah, modern-day parenting. Caring for children and pets, maintaining a household, negotiating politely with other stressed parents about whose child hit who and how and why and what the consequences will be… beneath the surface of civilized life, Yasmin Reza’s God of Carnage portrays the absurdity and anger between two pairs of parents dealing with a physical altercation between their children.

Le Dieu du Carnage originally premiered in Zurich in 2006. Later translated from French into English by Christopher Hampton, God of Carnage and its translations have had multiple productions around the world. The English translation, set in Brooklyn instead of Paris, opened on Broadway in 2009, and the story was adapted into a film, Carnage, which premiered in 2011 and was directed by Roman Polanski. Thunderbird Garage Productions remounts the play in the intimacy of a small L.A. theatre, dousing us in the agitation and discomfited humor of upper middle-class parents.

In the play, Michael (Eric Larson) and Veronica (Olga Konstantulakis) cordially host Alan (Kristian Kordula) and Annette (Andrea Lwin)–the parents of a boy who has just injured their son. Over espresso, clafouti, and verbal niceties, they gradually descend into shambles as their prejudices and judgmental behaviors are exposed. Under Kim Quinn’s direction, frustration and anger prevail at an intense volume, at times overpowering portrayals of disgust, resentment, and shock. The fury is more apt when dialogue explodes into action—Konstantulakis displays splendid rage when she pummels her husband, as does Lwin when she wreaks havoc on her husband’s phone. Kordula and Larson likewise draw laughs from the audience with their comedic timing and well-placed silences, adding sardonic texture to the baseline of ire.

The set is simple yet detail-oriented (built by Eric Larson), with modern art sculptures delineating the room and a massive black, white, and maroon abstract painting reflecting the characters’ collective internal chaos. Jacob Nguyen’s lighting design subtly tracks the realistic time of the play through Venetian blind shadows, while his pre-show and post-show music evokes the friction between modern day expectations and more subconscious forces at play.

Created by four friends from Larry Moss acting workshops, this show marks Thunderbird Garage’s first production. Though there’s room for more emotional nuance in the characters’ journeys, it’s a treat to see a contemporary classic staged with such spirited earnestness.

“Men are so wedded to their gadgets,” fusses Annette, “It belittles them.” An evening with carnage should help with that.

Cristina Sandu Bio: Journalist Cristina-Ioana Sandu graduated from De Montfort University in the UK and is passionate about photography, cinema, music, and storytelling. With a background rooted in journalism and media, Cristina brings a vibrant perspective to her work, shaped by hands-on experience in the film industry and live event production.

Her journey also includes crafting compelling narratives that explore identity, art, and human connection. Her blog acts as a personal and creative space to document life, celebrate authenticity, and highlight significant voices in arts and culture. Discover more at: www.cristinaioanasandu.com

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

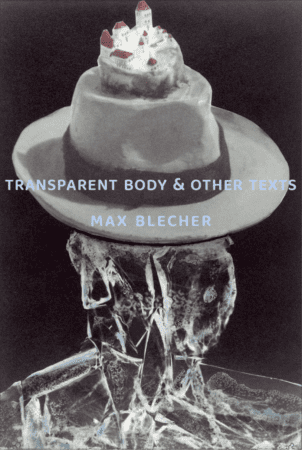

Review: Transparent Body & Other Texts by Max Blecher

| Author | Max Blecher |

| Translated By | Gabi Reigh |

| Genre | Fiction, Poetry, Letters |

| Language(s) | Romanian |

| Format | 174 Pages |

| Publisher | Twisted Spoon Press |

| ISBN | 9788088628033 |

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

The only thing more magical than receiving a letter from a friend is reading the letters of a writer you admire, and feeling as if they were sent to you. Translated from Romanian by Gabi Reigh, Transparent Body and & Other Texts collects poems, short prose, aphorisms, doodles, interviews—and best of all, letters—by the Romanian Jewish interwar writer Max Blecher. Reading Blecher’s work 80 years after his death feels as intimate and resonant as catching up with an old friend who has suffered and cared deeply.

Transparent Body was first published as a limited-edition release in 1934 when Blecher was 25 years old. By that time, he had been suffering from spinal tuberculosis for over 6 years, shuffling between various sanatoria before returning to his hometown in Botoșani, Romania. Despite his illness, he continued to write and publish texts that vibrate with urgency, intensity, and surrealism.

In the short triptych story “IX – MIX – FIX,” the narrator relates a bizarre scenario with emotional distance yet keen attention to the nightmarish physics that dissolves corporal and spiritual experiences into one. During one scene, he writes:

“I flew through chaotic chambers walled by bulbous, diseased clouds. I was hanging by the belly of a flying half-dog, my fingers digging into its flesh. But my legs were too long and, as they manically raced on the metal floor, metre-high sparks burst under my feet. Solitude chased me, flying towards me with a keener, sharper melancholy: I could no longer tell whether the rush of speed raced through my body or my soul.”

Blecher’s aphorisms also reflect cynical Romanian humor:

“Some people make others miserable by oppressing them, while others, conversely, by supporting them.”

Others, poetic despair:

“It is the magnetism of the abyss that looms over every conversation.”

Reading the list of aphorisms in one sitting feels a touch overwhelming: each maxim is a finely-cut gem of philosophy that deserves its own moment of contemplation.

The collection also has dozens of letters that reveal a different side of Blecher, more emotional and intimate, with humor that is less heavy and more sparkling.

In a letter dated May 16, 1930, to the French avant-garde poet Pierre Minet, he writes in response to a missed phone call from Minet about accidentally leaving a map in his carriage. The letter meanders to the 20-year-old Blecher describing his feelings of exasperated loneliness as he convalesces in the northern French commune of Bereck-sur-Mer. Some of his humor and frustration bursts out, provoking sympathy in the reader for this young artist who is deeply held back by his ill health and circumstances: “Of course, I am reliably informed that ordinary life is desperately idiotic, but I haven’t experienced it for myself!”

Other correspondence includes Blecher’s letters to other European literati such as Valerie Ionescu (editor of magazine Viața literatură), Alexandru Binder (editor of unu, which published works by other seminal Romanian modernist writers), and Geo Bogza (Romanian interwar avant-garde poet and early Surrealist). Blecher muses on his projects and artistic process, his family members and health, and his wishes and affection. Reigh’s translation beautifully portrays his vulnerability and shifting emotions, and an ample amount of footnotes in the correspondence provides more historical context for Blecher and his colleagues.

Although he passed away in 1938 at the age of 28, Blecher produced a stunning body of work in a short time. Transparent Body & Other Texts gives Anglophone literature an insight into a lesser-known avant-garde author—and not only through his surrealist fiction and prose, but to his struggles, doubts, and hopes.

Max Blecher’s novel Scarred Hearts was made into a film by one of the top Romanian filmmakers, Radu Jude.

Cristina Sandu Bio: Journalist Cristina-Ioana Sandu graduated from De Montfort University in the UK and is passionate about photography, cinema, music, and storytelling. With a background rooted in journalism and media, Cristina brings a vibrant perspective to her work, shaped by hands-on experience in the film industry and live event production.

Her journey also includes crafting compelling narratives that explore identity, art, and human connection. Her blog acts as a personal and creative space to document life, celebrate authenticity, and highlight significant voices in arts and culture. Discover more at: www.cristinaioanasandu.com

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Review: Stalin’s Master Class

| Location | Odyssey Theater, Los Angeles, CA |

| Date of Performance | June 2, 2024 |

| Language(s) | English |

| Photos by Jenny Graham | Amanda L. Andrei |

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

A kick to a cane and a man falls to his knees. A command to sing and fear fills the singers’ eyes. These small cruelties inhabit the spacious room of Stalin’s Master Class as the full terror of the regime stays subdued.

The lion’s share of danger resides with the historical figure of Josef Stalin, the Georgian dictator responsible for the deaths of millions across Eastern Europe as he consolidated power into the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR or Soviet Union), a world superpower from 1922 to 1991. By the time this play was written in 1984 by British playwright David Pownall, the dictator had been dead for thirty years, the Soviet Union was entering an era of decline, and Cold War tension ran high with nuclear threat.

Odyssey Theatre’s restaging of this satirical drama is a fascinating choice for 2024, as the memory of Stalin has faded, but global concerns over authoritarianism and populism remain high.

Based on events from a musician’s conference in January 1948 at the Kremlin, where Secretary of the Communist Party Andrei Zhdanov summoned musicians and music critics to deride their aesthetics and adherence to formalism, Stalin’s Master Class extends and fictionalizes the scenario further. Zhdanov (John Kayton) invites two composers, Dmitri Shostakovich (Randy Lowell) and Sergei Prokofiev (Jan Monroe), to a private audience with Stalin (Ilia Volok) at the Kremlin. And an invitation from an autocrat is never just an invitation.

In this case, the invitation meanders between philosophizing about the relationships between high and folk art, playing piano under threat, and eventually forcing a nightmarish creative jam session in an attempt to create a new Soviet culture. Director Ron Sossi finds the comic absurdist moments amidst the political palaver, revealing the true-to-life incongruity of regimes bent on hammering the arts into their agendas–and the awkward and soul-crushing failures that result. Dark crimson and iron reds in the plush furniture, sizable curtains, and a priceless icon (scenic designer Pete Hickok and prop designer Jenine Macdonald) likewise reflect the tension of an authority striving to maintain social realism while tempted by the bourgeoisie and royal taste.

John Kayton’s Zhdanov lives in this world of social realism and pragmatism, radiating his disgust with the composers in every shot of vodka he takes. Randy Lowell (as Dmitri Shostakovich) and Jan Munroe (as Sergei Prokofiev) portray artists under pressure with rapt silences and careful rebuttals, aware that they could be exiled at any moment. Relief blooms in the room when any of them sit at the piano to play—musical direction by Nisha Sujatha Arunasalam transforms their abstract discussions into emotion when they strike the keys.

It’s also noteworthy that offstage, Arunasalam plays the majority of the songs beautifully (alternating with pianist Michael Redfield, and with Lowell gracefully playing the Shostakovich sections).

The standout of this performance is Ilia Volok as Stalin. Humanizing a dictator is tricky territory, as it runs the risk of absolving a ruler of past atrocities that still haunt people and nations in the present. With an erratic mix of warmth, aggression, and stillness, Volok masterfully inhabits the despot with the cunningness and unpredictability of a coiled tiger, ready to strike the musicians at any moment. Neither absolved nor indicted, Volok’s Stalin—even in his most sympathetic moments—serves as a cruel and capricious symbol brought to life.

If only Pownall had written the musicians with more fear injected into them. Their trepidation remains mostly interior, save for an odd plot point where Shostakovich goes to a side bathroom and wills himself aloud to survive—then returns into the main room and uncharacteristically picks up the icon that had previously been mocked.

The imbalance of power—and the means of demonstrating it mostly through conversation—eases the sense of danger and real violence that the dictator could inflict upon the composers. Additionally, while it doesn’t happen often, some of the actors’ Eastern European accents slip into American ones, breaking the illusion of their characters. During intermission, and as I left the theater, I heard slivers of conversation about Putin, Ukraine, and world wars. It’s not merely Cold War shadows that still haunt us–It’s the ghosts of the current war. And as long as history keeps repeating itself, it seems that Stalin’s Master Class will keep enrolling.

Cristina Sandu Bio: Journalist Cristina-Ioana Sandu graduated from De Montfort University in the UK and is passionate about photography, cinema, music, and storytelling. With a background rooted in journalism and media, Cristina brings a vibrant perspective to her work, shaped by hands-on experience in the film industry and live event production.

Her journey also includes crafting compelling narratives that explore identity, art, and human connection. Her blog acts as a personal and creative space to document life, celebrate authenticity, and highlight significant voices in arts and culture. Discover more at: www.cristinaioanasandu.com

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!