Review: First Light by Zafer Şenocak

| Author | Zafer Şenocak |

| Translated By | Kristin Dickinson |

| Genre | Poetry |

| Language(s) | Turkish, English |

| Format | 160 Pages |

| Publisher | Zephyr Press |

| ISBN | 978-1-938890-30-7 |

Reviewed by Allie Rigby

What does it mean to exist in one place, physically, but mentally and emotionally exist elsewhere, simultaneously suspended in past, present, and future? Such time-warped entanglement ricochets throughout Zafer Şenocak’s bilingual poetry collection, First Light, translated from Turkish into English by Kristin Dickinson (Zephyr Press, 2024).

Many of the poems speak to the ideas of memory, language, and home, home being an ethereal concept often–if not ever so slightly–out of reach; accessible in wisps, dreams, and impressions that linger as briefly as morning light.

Şenocak’s poems ache with longing and acknowledgments of human contradictions. The original poem unfolds on the left page, in Turkish, and on the right lays the English translation.

In the poem, Muammaydun or I was a riddle (pg. 68-69), the speaker’s voice aches with loneliness and the universal desire to be known:

“I didn’t want to be an I

I wanted there to be someone

Yearning for me

My faithful companion

When you reach me

Let me be known” (Lines 16-21).

The “you” is an especially compelling address in this poem and throughout the collection. Is “you” a lover? The reader? A deeper, spiritual companion? The “cosmos” as Dickinson writes in the opening text “Unraveling the Self in Translation”? All of the above? With the “you” address, readers are brought into an intimate conversation between the speaker and someone. How readers interpret the “you” will influence each subsequent reading of the poem. But rather than get too stuck on who this “you” may be, I ask myself what the poet Brynn Saito encourages her students to ask themselves, when reading a poem for the first few times: how does the poem make me feel?

After reading I was a riddle I initially felt soothed by the longings I shared with the speaker; I also felt forlorn that loneliness was so inevitable. The repetition of “I” in Line 16 has a sense of contraction in itself–only through the “I” can the speaker express who they do and don’t want to be, and how to break free of the loneliness of the singular “I” is simultaneously impossible and desired.

The last two lines provide the solace, the hope, that someone, or something, will enter the speaker’s life and see them truly. Does this happen at death? Or before, via spiritual companionship? Or perhaps with deep friendship? Like many poets whose writing I admire, Şenocak does not answer it explicitly, but rather, lets us revel–and struggle–with the questions.

It’s impossible to ignore the role of language in any work of translation. Those who are familiar with Şenocak’s impressive canon of work, which according to his bio on Zephyr Press, includes “ten books of poetry, seven novels, and five essay collections” may know that he wrote much of his earlier work in German first, rather than in Turkish. Zephyr Press published Door Languages in 2008, which Şenocak wrote in German and Elizabeth Oehlkers Wright translated into English. First Light was written in Turkish first, as is much of Şenocak’s recent work. Translation is an art and an interpretation, the initial language of a text will influence the subsequent translations.

The relationship between language and home is deeply intertwined in this collection. In Kalbini üzme or Don’t trouble your heart (pg. 30-31), the poem flows from the title as:

“May the dust surrounding it

Never tire you

Neither home nor homesickness will come of that dust

You’ve tried enough

To make a home at the water’s edge” (Lines 1-5).

What troubles the speaker here is not the inevitability that dust falls around the heart, but rather the exhaustion that comes from this dust. There is a gentle acceptance in this address, an invitation to imagine a different kind of home: whatever actions the addressed “you” has made to make a home have not succeeded. The rich image of making a home at the water’s edge is once again soothing and promising, and yet, the speaker here reminds the “you” that they can pause that home-making attempt.

What then, does it mean, to forgo making a home? Or is home not a physical thing to make, but only possible in the form of language, itself? To be at home in language.

To–as Şenocak closes that poem–“Let the knots in your throat open.” Each poem then, an experiment into untying more of the ropes that bind us.

Allie Rigby is a poet, editor, and reviewer with roots in Orange County, California. She is the author of Moonscape for a Child (Bored Wolves, 2024) and the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship to Romania, where she taught creative writing at Universitatea Ovidius din Constanța. She holds a master’s degree in English: Creative Writing from San Francisco State University. She enjoys connecting with people to develop and share stories that generate cross-cultural dialogue, solidarity, and change. For more of her work and upcoming events, visit www.allierigby.com or @allie.j.rigby.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

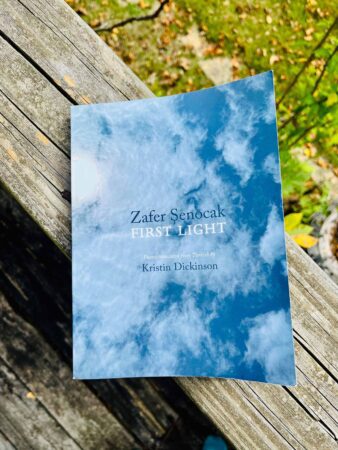

Review: Transparent Body & Other Texts by Max Blecher

| Author | Max Blecher |

| Translated By | Gabi Reigh |

| Genre | Fiction, Poetry, Letters |

| Language(s) | Romanian |

| Format | 174 Pages |

| Publisher | Twisted Spoon Press |

| ISBN | 9788088628033 |

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

The only thing more magical than receiving a letter from a friend is reading the letters of a writer you admire, and feeling as if they were sent to you. Translated from Romanian by Gabi Reigh, Transparent Body and & Other Texts collects poems, short prose, aphorisms, doodles, interviews—and best of all, letters—by the Romanian Jewish interwar writer Max Blecher. Reading Blecher’s work 80 years after his death feels as intimate and resonant as catching up with an old friend who has suffered and cared deeply.

Transparent Body was first published as a limited-edition release in 1934 when Blecher was 25 years old. By that time, he had been suffering from spinal tuberculosis for over 6 years, shuffling between various sanatoria before returning to his hometown in Botoșani, Romania. Despite his illness, he continued to write and publish texts that vibrate with urgency, intensity, and surrealism.

In the short triptych story “IX – MIX – FIX,” the narrator relates a bizarre scenario with emotional distance yet keen attention to the nightmarish physics that dissolves corporal and spiritual experiences into one. During one scene, he writes:

“I flew through chaotic chambers walled by bulbous, diseased clouds. I was hanging by the belly of a flying half-dog, my fingers digging into its flesh. But my legs were too long and, as they manically raced on the metal floor, metre-high sparks burst under my feet. Solitude chased me, flying towards me with a keener, sharper melancholy: I could no longer tell whether the rush of speed raced through my body or my soul.”

Blecher’s aphorisms also reflect cynical Romanian humor:

“Some people make others miserable by oppressing them, while others, conversely, by supporting them.”

Others, poetic despair:

“It is the magnetism of the abyss that looms over every conversation.”

Reading the list of aphorisms in one sitting feels a touch overwhelming: each maxim is a finely-cut gem of philosophy that deserves its own moment of contemplation.

The collection also has dozens of letters that reveal a different side of Blecher, more emotional and intimate, with humor that is less heavy and more sparkling.

In a letter dated May 16, 1930, to the French avant-garde poet Pierre Minet, he writes in response to a missed phone call from Minet about accidentally leaving a map in his carriage. The letter meanders to the 20-year-old Blecher describing his feelings of exasperated loneliness as he convalesces in the northern French commune of Bereck-sur-Mer. Some of his humor and frustration bursts out, provoking sympathy in the reader for this young artist who is deeply held back by his ill health and circumstances: “Of course, I am reliably informed that ordinary life is desperately idiotic, but I haven’t experienced it for myself!”

Other correspondence includes Blecher’s letters to other European literati such as Valerie Ionescu (editor of magazine Viața literatură), Alexandru Binder (editor of unu, which published works by other seminal Romanian modernist writers), and Geo Bogza (Romanian interwar avant-garde poet and early Surrealist). Blecher muses on his projects and artistic process, his family members and health, and his wishes and affection. Reigh’s translation beautifully portrays his vulnerability and shifting emotions, and an ample amount of footnotes in the correspondence provides more historical context for Blecher and his colleagues.

Although he passed away in 1938 at the age of 28, Blecher produced a stunning body of work in a short time. Transparent Body & Other Texts gives Anglophone literature an insight into a lesser-known avant-garde author—and not only through his surrealist fiction and prose, but to his struggles, doubts, and hopes.

Max Blecher’s novel Scarred Hearts was made into a film by one of the top Romanian filmmakers, Radu Jude.

Cristina Sandu Bio: Journalist Cristina-Ioana Sandu graduated from De Montfort University in the UK and is passionate about photography, cinema, music, and storytelling. With a background rooted in journalism and media, Cristina brings a vibrant perspective to her work, shaped by hands-on experience in the film industry and live event production.

Her journey also includes crafting compelling narratives that explore identity, art, and human connection. Her blog acts as a personal and creative space to document life, celebrate authenticity, and highlight significant voices in arts and culture. Discover more at: www.cristinaioanasandu.com

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

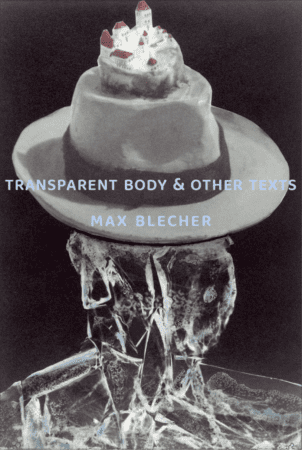

Review: Did This Hand Kill?

| Author | Cezary Lazarewicz |

| Genre | Nonfiction: True Crime |

| Language(s) | English |

| Format | 264 Pages |

| Publisher | Open Letter Books |

| ISBN | 978-1-948830-79-9 |

| Photos by Jenny Graham | Mihaela-Adina Drăgan |

Reviewed by Mihaela-Adina Drăgan

Imagine standing in a courtroom, the air thick with tension, as an accused woman faces witnesses and the jury. This is the riveting story Cezary Łazarewicz unravels in his nonfiction book, Did This Hand Kill? (Open Letter, 2024), translated by Sean Gasper Bye.

This is an enthralling exploration divided into two distinct parts: The first part meticulously reconstructs the dramatic events that transpired in the villa at Brzuchowice, near Lviv, Poland, on the nights of December 30–31, 1931. Łazarewicz delves into the ensuing trial and the widespread social and media frenzy that accompanied it. The second part of the book ventures into the shadowy aftermath of the accused governess, Margarita Emilia Gorgonowa, and how her life after 1939 unfolded. The haunting question remains: Was Gorgonowa justly convicted? Is justice even possible?

Łazarewicz draws heavily from the case files, preserved in state archives, and from contemporary press reports, thus reconstructing the evidence proceedings and trials, including the witness statements and the arguments (of both prosecution and defense) with impeccable accuracy. Even without having perused the original files, one can sense the intricate craftsmanship of this 20th century judicial process, surprisingly akin to modern-day proceedings.

It is striking how the legal institutions and mechanisms today mirror those from that 1930s Poland, as we attempt to approach the truth of blurry events.

The author vividly captures the charged atmosphere surrounding the trial, the pervasive social and media hysteria, and the relentless pursuit of sensationalism. Journalists, especially when dealing with sensitive and emotionally charged topics, may be tempted to exaggerate or contribute to false narratives based solely on imagination or to keep readers engaged.

Łazarewicz presents this phenomenon well. He also shares alternative theories that surfaced during the trial, or emerged later. His portrayal of the Brzuchowice villa as a domestic hell is compelling, and complicates the case. He also takes his time to build the tension, from the moment when Henryk Zaremba finds out his daughter, Luisa, is dead, to the excruciating trial itself–and all the fear and guilt that came with it.

The second part of Łazarewicz’s narrative is a detective-like quest to piece together the wartime and post-war fate of Rita Gorgonowa from fragmented information. When discussing Rita, the author relies on the perspectives of those who knew her, leaving it to the readers to discern which psychological profiles resonate as truthful.

The author beautifully depicts the shift in Zaremba’s perspective as the lover of Rita. Initially, he viewed Gorgonowa as a savior and the perfect addition to their family. Over time, he grew to see her less as a nursemaid and more as the “Lady of the House” (Łazarewicz 71). Zaremba wrote how:

‘Her laugh filled the garden on that very first Sunday. She conquered the hearts of my

little ones. They took to her immediately. The children, hitherto shabby, began to look

cleaner. The positive impression she made grew week by week, month by month.’

(Łazarewicz 71)

Fast forward to the night of his daughter’s death and its aftermath, where he begins to view her with suspicion. He notices every change in her behavior, every detail out of place, any gesture that might seem lacking in empathy, and any ill-conceived remark she intended to be humorous. Łazarewicz recounts those moments on pages 19–20 with gorgeous detail:

Rita, whom Zaremba observes out of the corner of his eye, doesn’t come near the bed.

She’s wearing green slippers and a heavy, brown fur coat with a collar. ‘Must

you put on a fur coat when someone shouts ‘murder’?’“Henryk darling,’ she whispers in his ear. ‘I’m worried about you. Pull yourself together.

What’s done can’t be undone.’Henryk darling doesn’t reply.’

Adina Drăgan

Could it be that Gorgonowa was so accustomed to taking that coat and slippers when leaving her room that she did it instinctively? Was she the murderer? I suppose readers will never know for sure. That’s part of the appeal of this unsolved mystery–how do we approach the truth of gruesome misdeeds?

Łazarewicz’s strength lies in his ability to maintain a judicious distance, refraining from imposing his own views on the reader. He is thorough and persistent in his investigation, giving voice to all parties, including those with seemingly far-fetched theories. The narrative leaves readers grappling with a question that may never be answered, as time, war, and the fallibility of human memory shroud the truth. Reflecting on the final verdict, one might conclude that the court itself was left unconvinced of Gorgonowa’s guilt or innocence.

It is remarkable how, despite the motion of time, human nature remains constant while only the tools evolve. Today, the Gorgonowa case might dominate internet headlines, with spin-off content as social media reels, hot takes, podcast updates, and more.

But in the 1930s, newspapers were the main way information was dispensed, and sensationalized, which this book conveys well. Daily updates on the trial kept readers glued; it was entertainment for the public consumption, as well as a botched attempt at journalistic integrity, perhaps.

Written in accessible, vivid prose free from legal jargon, the book reads like a gripping crime novel despite being a factual report. Did This Hand Kill? is an outstanding act of reporting, undertaken so many years after the events and recovered from the aftermath, archival remnants of war, and is itself a testament to the author’s skill and dedication.

Mihaela-Adina Drăgan is a scriptwriter and aspiring filmmaker residing in Bucharest, Romania. Her writing is deeply intertwined with her emotions and experiences, drawing inspiration from her family, friends, and fleeting encounters with strangers who leave a lasting impression.

She primarily writes scripts, and she also has a passion for fiction and poetry. She recently received a bachelor’s degree in American Studies from Ovidius University of Constanța and is now a graduate student studying Society, Multimedia, and Spectacle at the University of Bucharest. To read more of her writing, visit https://substack.com/@adinadragan.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Review: MyLifeandMyLife

| Author | Melinda Mátyus |

| Genre | Fiction |

| ISBN | 978-1-946604-19-4 |

| Format | 140 pages |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Ugly Duckling Presse |

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

American poet Emily Dickinson once wrote to a family friend, “The heart wants what it wants – or else it does not care.” Her observation is apt for the stark and bold world of MyLifeandMyLife by Melinda Mátyus. Translated from the Hungarian by Jozefina Komporaly, this experimental novella from the perspective of a nameless woman in a fraught relationship pushes the boundaries of language by expressing the pressure and violence of doomed love.

The unnamed narrator becomes involved with a man named Márton who – despite their sexual relationship – she comes to know less and less. She meets him at movies, but they do not touch. For this woman, love is tantamount to the simplest of gestures, and her words cluster together as if whispered or sighed:

“Hold my hand.

I’dliketoholdyourhand, your hand, I’d like your hand.

I don’t have the courage to utter this.

I’d like my left hand to be in his right hand, so he can touch me with his fingers, first the middle of my palm, then the back of my hand, my wrist, and we canjustwalkandwalk, from one house to another, on and on, then turn around, and around again, cross to the other side, or stay on this side, our side.

To have my lefthandinyourrighthand, that’s what I’d like.” (Mátyus, 15)

Yet her wishes remain unfulfilled. Simplicity is overtaken by excess–in the form of art. In a series of power plays, Márton gifts the narrator expensive paintings that pierce her soul but further separate any semblance of emotional intimacy. “What kind of a world is the one where women fall in love and end up on their own?” she wonders (Mátyus, 16).

It’s a world full of off-colors and uncanny symbols in the artworks, such as blood spurting from a bride and a “whitewashedgrave” (Mátyus, 27). Over the course of a few years, the narrator receives four paintings: Bride’s Door by Helen Frankenthaler, Monitor by Robert Ryman, Running White by Ellsworth Kelly, and Self-Portrait by Paula Modersohn-Becker. It’s notable that the first three paintings are by American abstract artists, while the latter is by a German expressionist painter who was the first woman artist to paint a nude self-portrait (and who died suddenly due to childbirth complications).

The narrator realizes that with these paintings, “Márton is always sending me messages about love because he is incapable of talking about it” (Mátyus, 37). With contempt, she scratches them (her “signature”) with a red stiletto, a small vent of frustration against male expectations of female domesticity and sexuality. Although the final portrait activates her own self-recognition, her lover senses his loss of control, not only over the materiality of his gifts, but over her personhood. The confrontation is as chilling as the narrator’s interpretations of the paintings.

Komporaly’s translation renders a sense of fragility and powerlessness into a character who is wrestling with her contempt and the destructive mystery of eros. Komporaly’s translator’s note and András Visky’s afterword provide additional context to Mátyus’s work, noting the influence of theater and similarities to ancient tragedy. Indeed, with her flowing sentences and huddled words, the novella reads as a stage script for a poetically heightened solo show. It is not hard to imagine watching the narrator as a live actor testifying her innermost secrets, her quotidian observations, and her imminent despair. In a world where women fall in love and end up on their own, it is only their own words that will bear witness to their agony.

Cristina Sandu Bio: Journalist Cristina-Ioana Sandu graduated from De Montfort University in the UK and is passionate about photography, cinema, music, and storytelling. With a background rooted in journalism and media, Cristina brings a vibrant perspective to her work, shaped by hands-on experience in the film industry and live event production.

Her journey also includes crafting compelling narratives that explore identity, art, and human connection. Her blog acts as a personal and creative space to document life, celebrate authenticity, and highlight significant voices in arts and culture. Discover more at: www.cristinaioanasandu.com

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Pitch The SEEfest Review

The SEEfest Review is now accepting pitches on a rolling basis for essays and critiques covering film, literature, art, history, and music. Please review our guidelines before sending us your pitch.

We look forward to hearing from you. Due to the volume of pitches we receive, we may be unable to reply to each pitch, but we will do our best.

Details for Pitching The SEEfest Review

The SEEfest Review welcomes submissions for film and literary reviews that explore the complexity of South East Europe. We are also open to educational articles particularly ones that raise awareness of historically marginalized populations of people who live in South East Europe or are part of the diaspora.

Pitch Guidelines

The SEEfest Review now accepts pitches on a rolling basis for essays and criticism on film, literature, art, history, and music. Please note that pitches are short summaries of who you are, why you want to write this review, and how your angle can offer a unique examination of the topic at hand. Pitches are not full submissions.

Please review our published reviews for an idea of what we are looking for. In general, we prefer film, literature, and play reviews rather than, say, historical articles or general trends in the film industry. That said, we occasionally accept the latter as well, especially if they resonate with our mission. We ask that your final article be between 500 and 1,500 words.

To pitch us, please complete this form titled “Pitch The SEEfest Review.” Please wait for a response from our team before you pitch us again. Thank you.

We welcome simultaneous submissions, but please notify us if your piece gets selected for another publication as soon as you know. That way we don’t fall in love with a pitch that is no longer available for us to pursue.

You should hear from us within six weeks.Should you be rejected, please know that you can still continue to submit future pitches to us. If your pitch was accepted, we will be in touch with you to offer editorial guidance as you complete your article.

About Us

If you are new to SEEfest, welcome. Please review our mission to familiarize yourself with the kinds of stories we long to read and share with the world.

The SEEfest Review is an online publication part of the annual South East European Film Festival (SEEfest). Each spring, SEEfest educates about and promotes the cultural diversity of South East Europe through its annual presentations of films from this region and year-round screenings and programs. SEEfest organizes conferences and retrospectives, serves as the cultural hub and resource for scholars and filmmakers, and creates opportunities for cultural exchange between Southern California and South East Europe.

Visit the footer and subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news and film festival updates from SEEfest.

As a nonprofit, we also welcome your support in keeping international cinema part of the Los Angeles film scene.

Review: Night truck driver

Night truck driver, By Marcin Świetlicki

Translated from Polish by Elżbieta Wójcik-Leese

Poetry

ISBN 9781938890802

128 pages

Bilingual: Polish and English on facing pages

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

The world drips. Caught in some kind of thaw, circling a winter on the verge of melting into a dream, or a dream solidifying into a cold city, Marcin Świetlicki’s Night truck driver (Kierowca nocnej ciężarówki) translated by Elżbieta Wójcik-Leese, immerses us into icy, hypnopompic places where we can hear Death and other unseen forces calling to us—and maybe even respond to them.

The opening poem, “Preface,” invokes the biblical origins of Genesis, reset in 1960s Poland: a man, a woman, a snake, but also “a stupid apple tree,” “depots, dead buses. / Old lemonade bottles of that unusual shape.” Here are seeds of Świetlicki’s themes: an overpowering sense of menace between sleep and waking, entanglements between the masculine and feminine beyond mere mortals, set among noirish urban landscapes and frosty worlds. The final line, “We’ll be observing the advance of darkness” sets up the reader for the opaque stillness at the heart of winter, questioning what life, if any, remains beneath the cold.

“Everything drips” follows immediately with an imperative, or maybe even a plea: “Don’t come into my dreams, don’t. In one dream / drown for good and don’t show up in any other.” To whom is the speaker addressing? A relative, a lover, a stranger, a monster? The ambiguity of other people’s presences in this poem and others compounds the sense of unease, giving you the sense of a faintly remembered nightmare just out of reach, or a stranger passing by your unlit house. Later on, in “Saturday, an impulse” the speaker announces, “Evil has come to my dream,” after which a female presence instructs them to undress and return to bed where they embrace. Other poems suggest the speaker is themself a dream, conjured by a stone or a stone moon, or a person falls asleep in broad daylight, searching for a missive in the world of sleep. The space between dreamer and reverie is not simply porous or overlapping: it is all-encompassing, cavernous, dissolving into the ache of the unknown.

The female presence in the dreams, waking life, and spaces in between appears to be a lover, the mother of the speaker’s child—or perhaps many lovers, or many mothers—but also an anonymous, distant figure(s) who seems to be on a parallel yet displaced wavelength from the speaker. The speaker seems to be in constant dialogue with this presence and others like it, and even when those energies are absent from the poem’s scene, the speaker continues evoking, recalling, and defying them. Herein is the brilliance of Wójcik-Leese’s translation that melds this shadowy feminine presence with that eternal, ever-present mystery: Death.

One poem in particular showcases the paradox of having a relationship with that mystery. “Posthumous correspondence” (Korespondencja pośmiertna) takes the shape of a stage or screenplay script in which a Man dialogues with Death. Glancing on the left side of the page at the Polish, I observed that the poem followed a different structure, without the character/dialogue formatting.

Curious about this choice, I reached out to Wójcik-Leese, who explained that in Polish, death is grammatically feminine, and so verb endings signifying grammatic gender reveal which passages are spoken by Death and which passages are uttered by the other person. In their translation collaboration, Świetlicki suggested pointing out the different speakers in the exchange, which resulted in a fascinating version of the original poem in English. Both correspondents seem to be speaking aloud (as if in a script), but the framework of the text is as a letter. The reader feels the conflict and contradictions of their communication—not merely between speakers and what they speak of, but how they speak to each other and the plaintive rhythm of their exchange.

Towards the end of the collection, the poems become sparser, more like jottings and diary entries. It’s as if the narrator is integrating the past, musing over the present and future, where “Plastic soldiers utter their war cries” in the ironically titled, “First poem” which is the third to last in the volume. Maybe this is the first poem for a new world or worlds, a transition point for more. It’s significant that Świetlicki has written thirteen books of poetry and that Night truck driver is the first English language collection in his work, which Wójcik-Leese notes in the translator’s afterword “follows the chronology of his poetic life and the lives of his individual volumes.” One hopes that more translations will come, as Świetlicki and Wójcik-Leese capture so hauntingly and precisely the cold ache of being called—and caught—among many worlds.

Radio Interview with Trafika Europe where you can hear Elżbieta Wójcik-Leese read the poems in Polish and English.

Reviewer Amanda L. Andrei is a Filipina Romanian American playwright, literary translator, and teaching artist residing in Los Angeles by way of Virginia/Washington DC. She writes epic, irreverent plays that center the concealed, wounded places of history and societies from the perspectives of diasporic Filipina women, and she translates from Romanian and Filipino to English. For more information on her work and upcoming events, visit: www.AmandaLAndrei.com

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs, as well as our mission to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

The Museum of Unconditional Surrender by Dubravka Ugrešić – Book Review

The Museum of Unconditional Surrender

Translated into English by Celia Hawkesworth

Reviewed by Natasha Ravnik

While reading Dubravka Ugrešić’s book, The Museum of Unconditional Surrender, I wondered if humankind had learned anything. Although Ugrešić wrote this work between 1991 and 1996, when her homeland of Yugoslavia was being destroyed by war, her words remain current.

There are many threads in Ugrešić’s writing that are worth exploring, but I have limited this review to just one aspect of the work: the life of the exile.

The Museum of Unconditional Surrender is unusual from the beginning: it starts with a catalogue of the contents of the stomach of Roland the Walrus in the Berlin Zoo and continues with an experimental mixture of genres. The use of narrative from various viewpoints, diary entries, and quotations parallels the recurrent fragmentation effects of trauma on the psyche – shards of not fully put back together-able language, memories, and images, bring us back to a starting point that can never be the same.

By definition, an unconditional surrender is one in which no guarantees are given to the surrendering party. It can be demanded with the threat of complete destruction, extermination, or annihilation. To what kind of life does the refugee surrender to?

“Those are all cold, melancholy, objective images (or more precisely: verbal photographs) from a past life in a former country which it will never again be possible to connect into a whole,’ writes Mihajlo P. in a letter.”

The Museum of Unconditional Surrender is a disparate archive of the bleak reality of loss as a result of forced migration. The stories within are mournfully human – they endear with their naked vulnerabilities. Displayed openly like a pack of cigarettes on a card table at a flea market are the visceral consequences of a nation’s spontaneous dissolution.

“10. ‘Refugees are divided into two categories: those who have photographs and those who have none,’ said a Bosnian, a refugee.”

With exquisitely simple sentences, Ugrešić brings out complex truths – the utter senselessness of the effects of war is tied up with a tender bow. Her prose unfurls unexpectedly like a poem, a jewel offered on a platter of tears, shiny but dissolving.

“Like the train of a gown, he dragged after him his secret, which, it seems, bore the simple name: indifference.”

Much of the narration is from a singularly feminine viewpoint ranging from a quiet melancholy,

“What a woman needs most is air and water.”

to a lonesome inevitability,

“As she crossed the Yugoslav border she was suddenly afraid, either because of the custom official’s black mustache, or the finality of her decision. And as she opened her suitcase, thinking in panic that she still had time to change her mind and go back, it slipped out of her hand and scattered its modest contents over the floor. She remembers the rolling apples (“There were lots of them, lots of apples,’ she says. ‘I don’t know myself why I had packed so many.’) Her memory was stuck on that picture of apples rolling over the floor. And it was though the apples had made the decision and not her: she had to pick them all up, and then the train left…”

Dubravka Ugrešić’s gift is the struggle: internal and external – of longing for the seemingly impossible – simply to belong, and in peace. Descriptions of oppressive banality under communism mingle with the tell-tale vacant stupor of a person without a home, an address-less individual with no country or state, constantly in motion – unmoored due to outside circumstances.

Her words are precise, chosen with exquisite care. Much like a museum exhibit, many of her paragraphs are numbered, catalogued, and exact. Equally precise is the English translation.

The pain of exile is not pretty, but Ugrešić’s words capture a sadness that is quite beautiful. The real tragedy of losing one’s country and the baggage (or lack thereof) that goes with it, how this loss seeps into the cracks of everything, reaching the most nuanced recesses of one’s personal identity.

“I hear my heart beating in the darkness. Pit-pat, pit-pat, pit-pat…I feel touched, as though there were a lost mouse inside it, beating in fright against the walls. Somewhere far behind me the landscape of my deranged county is ever paler, here, in front of me, are steps that lead to nowhere.”

Dubravka Ugrešić is a literary powerhouse, and The Museum of Unconditional Surrender is a book to be savored again and again.

ABOUT THE REVIEWER

Natasha Ravnik is a first-generation Slovenian American writer living in the San Francisco Bay Area. She is fascinated by stories of cultural resilience, with a particular interest in women’s voices. Natasha is currently writing a fictional memoir based on Slovenian migration stories. Her documentary short film, “Moja Nonica – My Grandmother” was a finalist at the 2016 SEEfest Project Accelerator. A big fan of SEEfest, Natasha believes in the power of art to encourage dialogue, in the hope of finding mutual understanding. She is constantly searching for beauty and common ground.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs, as well as our mission to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!