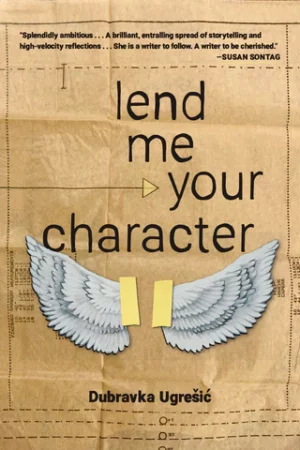

Review: Lend Me Your Character

| Author | Dubravka Ugrešić |

| Translators | Celia Hawkesworth, Michael Henry Heim, Ellen Elias-Bursac |

| Genre | Fiction |

| ISBN | 987-1-948830-64-5 |

| Format | 270 pages |

| Language | English |

| Original Language | Croatian |

| Publisher | Open Letter |

Reviewed by Allie Rigby

Dubravka Ugrešić’s Lend Me Your Character is a kaleidoscopic amalgamation featuring one novella, seven short stories, and several sections of author’s notes. In classic Ugrešić form, fairy tale elements abound–magic, crass humor, textile allusions to sewing, grotesque imagery, repetition, and warnings fill the pages. Ugrešić is not shy about her reference to fairy tales: many of these stories were originally published in Zagreb as part the collection, Life is a Fairy Tale, in 1983.

With translations as recent as 2022 (from Croatian into English) and author’s notes that feel like behind-the-scenes bonuses, this collection from Open Letter Books is both humorous and serious. The stories often center hyperaware narrators interjecting themselves into the text, trying to do best for ordinary characters amid absurd situations. Ugrešić’s opening work, the novella “Štefica Cvek in the Jaws of Life” that was translated by Celia Hawkesworth, plays with the idea of storyteller as clothier and clothier as storyteller. Chapter titles like “Key to Symbols,” “The Pattern,” and “Designing the Garment” make this connection clear, as do various symbols dissecting sections of the story, which can be decoded if readers refer to the “Key to Symbols” chapter. These visual cues implore the reader to “Cut the text along the dotted line,” or “Make a metatextual knot and pull tight as needed,” thus giving readers a more active role as recipients of the story (12).

Breaking the fourth wall is one of Ugrešić’s signature moves and while these directional symbols give the novella a choppy feel, it does blur the line between fiction and reality, which the author does throughout her fiction. Sadly, we can no longer ask Ugrešić about her fascination with textile fairy tale motifs–the buttons, the sewing, and the like–she died in Amsterdam on March 17, 2023. Only one month before her story collection debuted from Open Letter Books, Ugrešić passed, reportedly surrounded by “family and friends.”

Now readers are left with this last and most recent collection of Ugrešić, unless something comes out of the woodwork from her literary estate. After her novella, Ugrešić offers her first set of author’s notes under “Finishing Touches,” translated by Celia Hawkesworth, followed by “How to Ruin Your Own Heroine,” translated by Ellen Elias-Bursać. Finally, we have seven short stories. “The Kharms Case” and “A Hot Dog in a Warm Bun” may stir the most conversation for their hilarity. “Who Am I?” and “Button, Button, Who’s Got the Button?” carry Ugrešić’s curiosity for textile objects and their symbolic potential.

What next, for characters and for readers of Ugrešić? “I have to keep sewing, Štefica, your loose ends can’t be tied up just yet,” Ugrešić writes in her novella (58). For now, assemble the fabrics and find a proper place for each button.

Allie Rigby is a poet, editor, and educator with roots in Orange County. In 2023, she completed a year-long Fulbright fellowship in Romania where she taught creative writing at Universitatea Ovidius din Constanța. She holds a master’s degree in English: Creative Writing from San Francisco State University. Allie loves connecting with people to develop and share impactful stories that generate cross-cultural dialogue. For her most recent book of poetry and other writing, please visit www.allierigby.com or @allie.j.rigby.

The Museum of Unconditional Surrender by Dubravka Ugrešić – Book Review

The Museum of Unconditional Surrender

Translated into English by Celia Hawkesworth

Reviewed by Natasha Ravnik

While reading Dubravka Ugrešić’s book, The Museum of Unconditional Surrender, I wondered if humankind had learned anything. Although Ugrešić wrote this work between 1991 and 1996, when her homeland of Yugoslavia was being destroyed by war, her words remain current.

There are many threads in Ugrešić’s writing that are worth exploring, but I have limited this review to just one aspect of the work: the life of the exile.

The Museum of Unconditional Surrender is unusual from the beginning: it starts with a catalogue of the contents of the stomach of Roland the Walrus in the Berlin Zoo and continues with an experimental mixture of genres. The use of narrative from various viewpoints, diary entries, and quotations parallels the recurrent fragmentation effects of trauma on the psyche – shards of not fully put back together-able language, memories, and images, bring us back to a starting point that can never be the same.

By definition, an unconditional surrender is one in which no guarantees are given to the surrendering party. It can be demanded with the threat of complete destruction, extermination, or annihilation. To what kind of life does the refugee surrender to?

“Those are all cold, melancholy, objective images (or more precisely: verbal photographs) from a past life in a former country which it will never again be possible to connect into a whole,’ writes Mihajlo P. in a letter.”

The Museum of Unconditional Surrender is a disparate archive of the bleak reality of loss as a result of forced migration. The stories within are mournfully human – they endear with their naked vulnerabilities. Displayed openly like a pack of cigarettes on a card table at a flea market are the visceral consequences of a nation’s spontaneous dissolution.

“10. ‘Refugees are divided into two categories: those who have photographs and those who have none,’ said a Bosnian, a refugee.”

With exquisitely simple sentences, Ugrešić brings out complex truths – the utter senselessness of the effects of war is tied up with a tender bow. Her prose unfurls unexpectedly like a poem, a jewel offered on a platter of tears, shiny but dissolving.

“Like the train of a gown, he dragged after him his secret, which, it seems, bore the simple name: indifference.”

Much of the narration is from a singularly feminine viewpoint ranging from a quiet melancholy,

“What a woman needs most is air and water.”

to a lonesome inevitability,

“As she crossed the Yugoslav border she was suddenly afraid, either because of the custom official’s black mustache, or the finality of her decision. And as she opened her suitcase, thinking in panic that she still had time to change her mind and go back, it slipped out of her hand and scattered its modest contents over the floor. She remembers the rolling apples (“There were lots of them, lots of apples,’ she says. ‘I don’t know myself why I had packed so many.’) Her memory was stuck on that picture of apples rolling over the floor. And it was though the apples had made the decision and not her: she had to pick them all up, and then the train left…”

Dubravka Ugrešić’s gift is the struggle: internal and external – of longing for the seemingly impossible – simply to belong, and in peace. Descriptions of oppressive banality under communism mingle with the tell-tale vacant stupor of a person without a home, an address-less individual with no country or state, constantly in motion – unmoored due to outside circumstances.

Her words are precise, chosen with exquisite care. Much like a museum exhibit, many of her paragraphs are numbered, catalogued, and exact. Equally precise is the English translation.

The pain of exile is not pretty, but Ugrešić’s words capture a sadness that is quite beautiful. The real tragedy of losing one’s country and the baggage (or lack thereof) that goes with it, how this loss seeps into the cracks of everything, reaching the most nuanced recesses of one’s personal identity.

“I hear my heart beating in the darkness. Pit-pat, pit-pat, pit-pat…I feel touched, as though there were a lost mouse inside it, beating in fright against the walls. Somewhere far behind me the landscape of my deranged county is ever paler, here, in front of me, are steps that lead to nowhere.”

Dubravka Ugrešić is a literary powerhouse, and The Museum of Unconditional Surrender is a book to be savored again and again.

ABOUT THE REVIEWER

Natasha Ravnik is a first-generation Slovenian American writer living in the San Francisco Bay Area. She is fascinated by stories of cultural resilience, with a particular interest in women’s voices. Natasha is currently writing a fictional memoir based on Slovenian migration stories. Her documentary short film, “Moja Nonica – My Grandmother” was a finalist at the 2016 SEEfest Project Accelerator. A big fan of SEEfest, Natasha believes in the power of art to encourage dialogue, in the hope of finding mutual understanding. She is constantly searching for beauty and common ground.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs, as well as our mission to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!