Pitch The SEEfest Review

The SEEfest Review is now accepting pitches on a rolling basis for essays and critiques covering film, literature, art, history, and music. Please review our guidelines before sending us your pitch.

We look forward to hearing from you. Due to the volume of pitches we receive, we may be unable to reply to each pitch, but we will do our best.

Details for Pitching The SEEfest Review

The SEEfest Review welcomes submissions for film and literary reviews that explore the complexity of South East Europe. We are also open to educational articles particularly ones that raise awareness of historically marginalized populations of people who live in South East Europe or are part of the diaspora.

Pitch Guidelines

The SEEfest Review now accepts pitches on a rolling basis for essays and criticism on film, literature, art, history, and music. Please note that pitches are short summaries of who you are, why you want to write this review, and how your angle can offer a unique examination of the topic at hand. Pitches are not full submissions.

Please review our published reviews for an idea of what we are looking for. In general, we prefer film, literature, and play reviews rather than, say, historical articles or general trends in the film industry. That said, we occasionally accept the latter as well, especially if they resonate with our mission. We ask that your final article be between 500 and 1,500 words.

To pitch us, please complete this form titled “Pitch The SEEfest Review.” Please wait for a response from our team before you pitch us again. Thank you.

We welcome simultaneous submissions, but please notify us if your piece gets selected for another publication as soon as you know. That way we don’t fall in love with a pitch that is no longer available for us to pursue.

You should hear from us within six weeks.Should you be rejected, please know that you can still continue to submit future pitches to us. If your pitch was accepted, we will be in touch with you to offer editorial guidance as you complete your article.

About Us

If you are new to SEEfest, welcome. Please review our mission to familiarize yourself with the kinds of stories we long to read and share with the world.

The SEEfest Review is an online publication part of the annual South East European Film Festival (SEEfest). Each spring, SEEfest educates about and promotes the cultural diversity of South East Europe through its annual presentations of films from this region and year-round screenings and programs. SEEfest organizes conferences and retrospectives, serves as the cultural hub and resource for scholars and filmmakers, and creates opportunities for cultural exchange between Southern California and South East Europe.

Visit the footer and subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest news and film festival updates from SEEfest.

As a nonprofit, we also welcome your support in keeping international cinema part of the Los Angeles film scene.

Review – Glass Onion

Set in Greece, Rian Johnson’s slick whodunnit is a repudiation of the tech craze, influencer culture, class privilege, and American hegemony abroad.

Warning: Contains Spoilers for Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery

By Vanessa Bloom

“I like the glass onion, as a metaphor. An object that seems densely layered, but in reality, the center is in plain sight.” Detective Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig) is back, and don’t let his distinctive twang distract you from the truths he has to tell. In this anticipated sequel to Knives Out, Blanc returns to solve yet another mystery, this time at billionaire Miles Bron’s (Edward Norton) private island in Greece (the film was shot in Greece and Serbia). Like the titular glass onion itself, this film has layers of meaning for the audience to peel back, everything from class differences to American influence in the world at large.

Before anyone argues that it’s “not meant to be that deep,” let me remind you that to assume so would be to underestimate writer/director Rian Johnson. From the biting sequences critiquing the White American Liberal in the first Knives Out (“‘Immigrants Get the Job Done!’” one character quotes while another replies, “I love Hamilton”; later in the film, these same characters threaten to report the heroine’s undocumented mother to I.C.E.) to Johnson’s real-life defense of Asian-American actress Kelly Marie Tran during the racist attacks she endured after starring in Star Wars VIII: The Last Jedi, Johnson knows what he’s doing.

He’s well aware of both his audience and himself, and has over a million followers on Twitter where he interacts with fans and trolls his haters (most notably conservative poster boy Ben Shapiro). Born into privilege himself (his childhood home in San Clemente, California was listed for $7.7 million in 2018) Rian Johnson nevertheless possesses an uncanny awareness of injustice in the world, and isn’t afraid to call it out when he sees it.

Johnson’s sensibilities are written out in his latest film, the Knives Out sequel Glass Onion. A fresh cast of American characters descend into chaos as their 21st century lives collide in Greece: the brilliant scientist Lionel Toussaint (Leslie Odom Jr.); image-obsessed politician Claire Debella (Katherine Hahn); former model turned loungewear entrepreneur Birdie Jay (Kate Hudson) and her long-suffering assistant Peg (Jessica Henwick); and gun-toting alpha male influencer Duke Cody (Dave Bautista), accompanied by his girlfriend who’s using him for her own political aspirations, Whisky (Madelyne Cline).

Each character has their secrets and they’re all part of a former friend group split apart when Andi Brand (Janelle Monáe) had a falling out with Miles over the tech company they created together. Janelle Monáe shines as the co-star of this movie, commanding the screen and demanding respect – from the other characters and the audience alike. She and Craig as Blanc make a formidable pair, her character’s highfalutin big-city accent contrasting delightfully with his Southern drawl. For his part, Edward Norton as Miles Bron plays up the Elon Musk-esque aspects of his character, the big ideas, the tech jargon, and the constant push for “progress” no matter what the cost (“I want to be responsible for something that gets talked about in the same breath as the Mona Lisa,” Miles declares).

The backdrop of Greece is something Johnson himself said was a creative decision to separate this film from its predecessor, Knives Out, set in the American state of Virginia. However, Johnson does more than show the beautiful scenery, he uses it to illustrate characters’ privilege. Glass Onion is set during the Covid-19 Pandemic, and like so many real-life well-off Americans who fled cities to move to beautiful yet typically lower-income areas, Miles Bron has a mansion on a Greek island and invites his American friends for a mask-free weeklong soirée. No matter that the staff driving or serving them have to be masked; Covid-19 is their problem for being poor.

Once at his mansion (which features a gigantic glass onion on the roof) we learn of Miles’ real plans: pushing his tech company’s hydrogen powered fuel to market as quickly as possible, despite warnings it’s highly explosive and not safety tested. Miles embodies the “move fast and break things” mentality that began with California’s tech elite in Silicon Valley and has since infected the world at large. The fact that Greece is thousands of miles from Miles’ company headquarters doesn’t protect the country from his machinations; it’s revealed later on that Miles is secretly running his mansion on the new, untested energy system. American dominance globally is perpetuated by wealth and status, and Miles Bron is no exception – he’s the rule.

The conflict between Miles’ friend group and the now-outcast Andi is also another excellent example of Johnson’s keen eye for spotting social inequality. Andi, a Black woman, is self-made and grew up lower-class in the American South. She changed her accent to fit in with her wealthy mostly white Northerner friends. So it makes sense Andi’s the target when the friend group sours. As we learn later, she was the only one to actually call Miles out, and he continued using her ideas to make the company successful. The others, basically writing Andi off as the Angry Black Woman stereotype, fall in line behind Miles.

Johnson knows a thing or two about mob mentality: five years later, he still limits his Instagram comments from when Star Wars fans spammed him with hate after the release of The Last Jedi in 2018. In Glass Onion, he does not hold back in portraying how Miles and his friends ostracized Andi, ultimately murdering her. Johnson also isn’t afraid to describe exactly what these characters are, through the words spoken by Benoit Blanc: “I expected complexity. I expected intelligence. I expected a puzzle, a game. But that’s not what any of this is. It hides not behind complexity, but behind mind-numbing obvious clarity.” The obvious clarity is that the characters of Glass Onion are a cross-section of the American elite, all scrambling to appease the current billionaire who’s going to fund their next project and get them up a couple of rungs up the ladder.

Everyone else is collateral, disposable beings that exist to serve the larger goal – not only Miles and his friends’ personal ambitions, but the more opaque notions of preserving wealth, stymying social advancement for the lower classes, and American influence abroad. Only when our heroes step in is justice delivered for the late Andi; even then, the rest of Miles’ posse don’t really learn anything. They only switch to being against Miles once it’s bad for their own reputations.

In Glass Onion, the American Dream curdles under the Greek sun. Johnson is an excellent, insightful writer, not only crafting a classic mystery but giving it a deeper meaning that’s more relevant than ever in the 21st century. While tech continues to grow, influencers influence, and billionaires profit off low-wage labor, the division between the wealthy and the poor also continues to grow. Simultaneously, American influence has spread across the globe, and shows no sign of stopping. Nowhere are all these issues on better display than in Glass Onion, where, like a master chef, Rian Johnson peels back the story … revealing that the outer layer and the core are one and the same.

Glass Onion is available on Netflix.

Vanessa Bloom is an emerging writer, educator, and filmmaker from Orange County, California. She was adopted from China in 1999, and her mom’s side is Jewish from the Balkans while her dad’s is Christian from the American Midwest. Her family is not only multiracial and multicultural, but also multifaith! With such a colorful background, Vanessa loves telling stories and has written everything from coming-of-age dramas to horror comedy. Her favorite type of story is one that makes her laugh. Vanessa has a B.A. in history and a teaching credential in social science from CSU Long Beach. She also is proud to be a Los Angeles Community Leader for The LUNAR Collective, an organization for and by Asian Jews. Find her work at linktr.ee/vanessabloom.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs, as well as our mission to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Review – I Do Not Take My Name for Granted

I Do Not Take My Name for Granted: Four Short films by Saodat Ismailova

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

March 6, 2023, at REDCAT, Roy and Edna Disney CalArts Theater

The longer you gaze at the steep cliffs, the more you start to see shapes of women. Vintage footage of Soviet tanks gives way to the dilating pupil of a tiger. And the image of women—whether preserved through oral tradition, a nation’s cinema, or a fading ritual of movement on a mountain—emerges from deep within the cultural memory of Saodat Ismailova’s four short films at REDCAT, curated by Jheanelle Brown.

Gulaim (2014) starts the journey, a monologue of the heroine Gulaim from the Central Asian epic Qyrq Qyz (40 Girls), a narrative preserved in the oral folklore of the Qaraqalpaqs, a Turkic group native to Karakalpakstan, an autonomous republic within Uzbekistan.

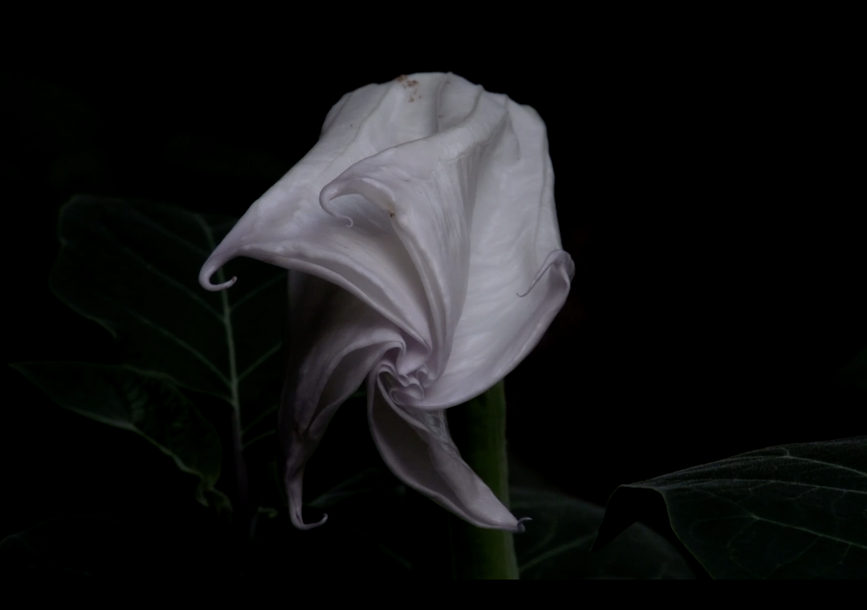

Cliffs bathed in setting sun rays mingle with closeups of a young woman’s face and hair, the blue flanks of a horse, and a blooming moonflower, as a narrator relates how her father used to shower her with affection in her childhood. Now she refuses to marry a man he has chosen for her, marking a new chapter in her life as she moves from favored daughter to something more liminal and uncertain.

The breathtaking landscapes and intimate details of hair, clothing, and animals—as well as surreal images of veils, chainmail, and a theatrical stage—draw the audience into both large and small scales of beauty and betrayal on ancient and modern levels.

The following film, The Haunted (2017), depicts an imaginary encounter with a Turkestan tiger that became extinct due to Russian colonization of Turkestan in the 1940s.

As sportsmen and military personnel hunted the tigers and the sacred animal’s habitats were converted into land for cotton crops, the tigers were declared extinct in the 1970s. A female voice quietly yet intensely mourns the loss of sacred love and connection over images of grainy black-and-white footage evoking colonization, which are juxtaposed against intense closeups of a live tiger’s eyes, whiskers, and deep fur.

Shots banks its former habitat are motionless amidst the river banks’ greenery, as if waiting for the empty space to once again be filled with soft pawprints and striped skin.

Her Five Lives (2020), commissioned as part of Asian Film Archive’s Monographs, a series of essays on Asian cinema, presents five different archetypes of heroines in Uzbek cinema from the past century, starting with Vyacheslav Viskovsky’s 1925 film, The Minaret of Death, based on a 16th century myth of the Bukharans, an ethnoreligious Jewish group in Central Asia.

Early silent black-and-white film of women as victims of patriarchy transitions into portrayals of women under communism, reform, perestroika, and eventually independence (albeit a confused one).

In contrast to the first two films, this short is faster paced and draws upon more recent cultural memory in the form of archival film, with some of the last footage from Ismailova’s 2014 film, Forty Days of Silence. It’s exciting to watch the transformation of the cinematic portrayal of Central Asian womanhood, making one wonder how to access and watch these films now.

The final film, Chillpiq (2018), depicts a group of girls climbing the ruins of Chillpiq, an ancient funerary structure founded by Zoroastrians and located in Karakalpakstan.

They surround a flag pole, tying rags and circling the pole in the light of the fading sun. From a visual standpoint, the film seems more like a documentary, grounded in realism and with steady shots of the young women as they climb up the mountain. But as they conduct their ritual in silent determination, there arises a feeling of quiet glory that only comes through steadfast devotion.

These contemporary women somehow know how to honor the earth and the unseen, and the earth and unseen return the honor.

While Ismailova’s films have been showcased in museums and film festivals, with her work currently held in collections of Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, this one-night event marked the first time that her films have been screened theatrically in Los Angeles.

Her films are a treasure, giving outsiders a rare glimpse into Central Asian ritual, history, and personhood. To see them in a cinema is a reverent experience, offering the chance to immerse ourselves in our own cultural memories and re-examine the myths, landscapes, and archetypes that we hold dear.

Reviewer Amanda L. Andrei is a Filipina Romanian American playwright, literary translator, and teaching artist residing in Los Angeles by way of Virginia/Washington DC. She writes epic, irreverent plays that center the concealed, wounded places of history and societies from the perspectives of diasporic Filipina women, and she translates from Romanian and Filipino to English. For more information on her work and upcoming events, visit: www.AmandaLAndrei.com

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

FILM REVIEW: I WAS AT HOME, BUT… AT AFI FEST 2019

SEEfest was proud to be the community sponsor for the screening of I Was at Home, But… (Ich War Zuhause, Aber…) at this year’s AFI Fest. The film by Angela Schanelec is a joint German and Serbian production and previously won the Silver Bear for Best Director award at the 2019 Berlin Film Festival. The well-attended screening was held on November 18 at the Chinese Theater. (more…)