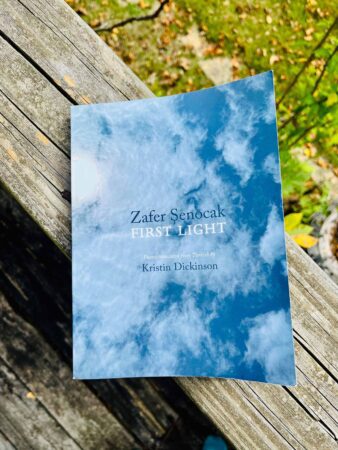

Review: First Light by Zafer Şenocak

| Author | Zafer Şenocak |

| Translated By | Kristin Dickinson |

| Genre | Poetry |

| Language(s) | Turkish, English |

| Format | 160 Pages |

| Publisher | Zephyr Press |

| ISBN | 978-1-938890-30-7 |

Reviewed by Allie Rigby

What does it mean to exist in one place, physically, but mentally and emotionally exist elsewhere, simultaneously suspended in past, present, and future? Such time-warped entanglement ricochets throughout Zafer Şenocak’s bilingual poetry collection, First Light, translated from Turkish into English by Kristin Dickinson (Zephyr Press, 2024).

Many of the poems speak to the ideas of memory, language, and home, home being an ethereal concept often–if not ever so slightly–out of reach; accessible in wisps, dreams, and impressions that linger as briefly as morning light.

Şenocak’s poems ache with longing and acknowledgments of human contradictions. The original poem unfolds on the left page, in Turkish, and on the right lays the English translation.

In the poem, Muammaydun or I was a riddle (pg. 68-69), the speaker’s voice aches with loneliness and the universal desire to be known:

“I didn’t want to be an I

I wanted there to be someone

Yearning for me

My faithful companion

When you reach me

Let me be known” (Lines 16-21).

The “you” is an especially compelling address in this poem and throughout the collection. Is “you” a lover? The reader? A deeper, spiritual companion? The “cosmos” as Dickinson writes in the opening text “Unraveling the Self in Translation”? All of the above? With the “you” address, readers are brought into an intimate conversation between the speaker and someone. How readers interpret the “you” will influence each subsequent reading of the poem. But rather than get too stuck on who this “you” may be, I ask myself what the poet Brynn Saito encourages her students to ask themselves, when reading a poem for the first few times: how does the poem make me feel?

After reading I was a riddle I initially felt soothed by the longings I shared with the speaker; I also felt forlorn that loneliness was so inevitable. The repetition of “I” in Line 16 has a sense of contraction in itself–only through the “I” can the speaker express who they do and don’t want to be, and how to break free of the loneliness of the singular “I” is simultaneously impossible and desired.

The last two lines provide the solace, the hope, that someone, or something, will enter the speaker’s life and see them truly. Does this happen at death? Or before, via spiritual companionship? Or perhaps with deep friendship? Like many poets whose writing I admire, Şenocak does not answer it explicitly, but rather, lets us revel–and struggle–with the questions.

It’s impossible to ignore the role of language in any work of translation. Those who are familiar with Şenocak’s impressive canon of work, which according to his bio on Zephyr Press, includes “ten books of poetry, seven novels, and five essay collections” may know that he wrote much of his earlier work in German first, rather than in Turkish. Zephyr Press published Door Languages in 2008, which Şenocak wrote in German and Elizabeth Oehlkers Wright translated into English. First Light was written in Turkish first, as is much of Şenocak’s recent work. Translation is an art and an interpretation, the initial language of a text will influence the subsequent translations.

The relationship between language and home is deeply intertwined in this collection. In Kalbini üzme or Don’t trouble your heart (pg. 30-31), the poem flows from the title as:

“May the dust surrounding it

Never tire you

Neither home nor homesickness will come of that dust

You’ve tried enough

To make a home at the water’s edge” (Lines 1-5).

What troubles the speaker here is not the inevitability that dust falls around the heart, but rather the exhaustion that comes from this dust. There is a gentle acceptance in this address, an invitation to imagine a different kind of home: whatever actions the addressed “you” has made to make a home have not succeeded. The rich image of making a home at the water’s edge is once again soothing and promising, and yet, the speaker here reminds the “you” that they can pause that home-making attempt.

What then, does it mean, to forgo making a home? Or is home not a physical thing to make, but only possible in the form of language, itself? To be at home in language.

To–as Şenocak closes that poem–“Let the knots in your throat open.” Each poem then, an experiment into untying more of the ropes that bind us.

Allie Rigby is a poet, editor, and reviewer with roots in Orange County, California. She is the author of Moonscape for a Child (Bored Wolves, 2024) and the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship to Romania, where she taught creative writing at Universitatea Ovidius din Constanța. She holds a master’s degree in English: Creative Writing from San Francisco State University. She enjoys connecting with people to develop and share stories that generate cross-cultural dialogue, solidarity, and change. For more of her work and upcoming events, visit www.allierigby.com or @allie.j.rigby.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

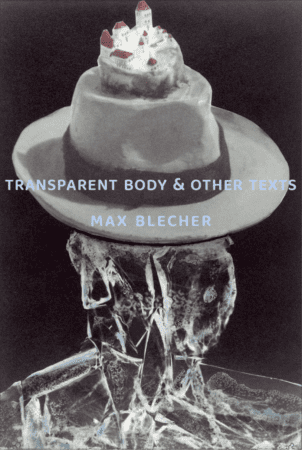

Review: Transparent Body & Other Texts by Max Blecher

| Author | Max Blecher |

| Translated By | Gabi Reigh |

| Genre | Fiction, Poetry, Letters |

| Language(s) | Romanian |

| Format | 174 Pages |

| Publisher | Twisted Spoon Press |

| ISBN | 9788088628033 |

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

The only thing more magical than receiving a letter from a friend is reading the letters of a writer you admire, and feeling as if they were sent to you. Translated from Romanian by Gabi Reigh, Transparent Body and & Other Texts collects poems, short prose, aphorisms, doodles, interviews—and best of all, letters—by the Romanian Jewish interwar writer Max Blecher. Reading Blecher’s work 80 years after his death feels as intimate and resonant as catching up with an old friend who has suffered and cared deeply.

Transparent Body was first published as a limited-edition release in 1934 when Blecher was 25 years old. By that time, he had been suffering from spinal tuberculosis for over 6 years, shuffling between various sanatoria before returning to his hometown in Botoșani, Romania. Despite his illness, he continued to write and publish texts that vibrate with urgency, intensity, and surrealism.

In the short triptych story “IX – MIX – FIX,” the narrator relates a bizarre scenario with emotional distance yet keen attention to the nightmarish physics that dissolves corporal and spiritual experiences into one. During one scene, he writes:

“I flew through chaotic chambers walled by bulbous, diseased clouds. I was hanging by the belly of a flying half-dog, my fingers digging into its flesh. But my legs were too long and, as they manically raced on the metal floor, metre-high sparks burst under my feet. Solitude chased me, flying towards me with a keener, sharper melancholy: I could no longer tell whether the rush of speed raced through my body or my soul.”

Blecher’s aphorisms also reflect cynical Romanian humor:

“Some people make others miserable by oppressing them, while others, conversely, by supporting them.”

Others, poetic despair:

“It is the magnetism of the abyss that looms over every conversation.”

Reading the list of aphorisms in one sitting feels a touch overwhelming: each maxim is a finely-cut gem of philosophy that deserves its own moment of contemplation.

The collection also has dozens of letters that reveal a different side of Blecher, more emotional and intimate, with humor that is less heavy and more sparkling.

In a letter dated May 16, 1930, to the French avant-garde poet Pierre Minet, he writes in response to a missed phone call from Minet about accidentally leaving a map in his carriage. The letter meanders to the 20-year-old Blecher describing his feelings of exasperated loneliness as he convalesces in the northern French commune of Bereck-sur-Mer. Some of his humor and frustration bursts out, provoking sympathy in the reader for this young artist who is deeply held back by his ill health and circumstances: “Of course, I am reliably informed that ordinary life is desperately idiotic, but I haven’t experienced it for myself!”

Other correspondence includes Blecher’s letters to other European literati such as Valerie Ionescu (editor of magazine Viața literatură), Alexandru Binder (editor of unu, which published works by other seminal Romanian modernist writers), and Geo Bogza (Romanian interwar avant-garde poet and early Surrealist). Blecher muses on his projects and artistic process, his family members and health, and his wishes and affection. Reigh’s translation beautifully portrays his vulnerability and shifting emotions, and an ample amount of footnotes in the correspondence provides more historical context for Blecher and his colleagues.

Although he passed away in 1938 at the age of 28, Blecher produced a stunning body of work in a short time. Transparent Body & Other Texts gives Anglophone literature an insight into a lesser-known avant-garde author—and not only through his surrealist fiction and prose, but to his struggles, doubts, and hopes.

Max Blecher’s novel Scarred Hearts was made into a film by one of the top Romanian filmmakers, Radu Jude.

Ioana Bîrjan (b.1997) is the author of Vârsta Iubirii which translates into English as The Age of Love (Heyday Books, 2023). The novel is inspired by the Lady of the Camellias and the opera La traviata. She earned a bachelor’s degree from the Faculty of Letters, Ovidius University of Constanța, where she is now a graduate student in the Romanian Studies program.

Read more of her work in magazines, in anthologies, and on her blog: https://scrierileioanei.wordpress.com/

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

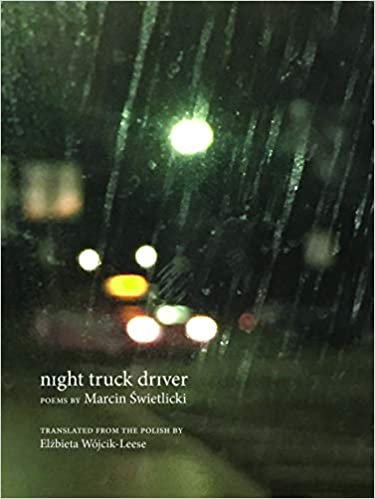

Review: Night truck driver

Night truck driver, By Marcin Świetlicki

Translated from Polish by Elżbieta Wójcik-Leese

Poetry

ISBN 9781938890802

128 pages

Bilingual: Polish and English on facing pages

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

The world drips. Caught in some kind of thaw, circling a winter on the verge of melting into a dream, or a dream solidifying into a cold city, Marcin Świetlicki’s Night truck driver (Kierowca nocnej ciężarówki) translated by Elżbieta Wójcik-Leese, immerses us into icy, hypnopompic places where we can hear Death and other unseen forces calling to us—and maybe even respond to them.

The opening poem, “Preface,” invokes the biblical origins of Genesis, reset in 1960s Poland: a man, a woman, a snake, but also “a stupid apple tree,” “depots, dead buses. / Old lemonade bottles of that unusual shape.” Here are seeds of Świetlicki’s themes: an overpowering sense of menace between sleep and waking, entanglements between the masculine and feminine beyond mere mortals, set among noirish urban landscapes and frosty worlds. The final line, “We’ll be observing the advance of darkness” sets up the reader for the opaque stillness at the heart of winter, questioning what life, if any, remains beneath the cold.

“Everything drips” follows immediately with an imperative, or maybe even a plea: “Don’t come into my dreams, don’t. In one dream / drown for good and don’t show up in any other.” To whom is the speaker addressing? A relative, a lover, a stranger, a monster? The ambiguity of other people’s presences in this poem and others compounds the sense of unease, giving you the sense of a faintly remembered nightmare just out of reach, or a stranger passing by your unlit house. Later on, in “Saturday, an impulse” the speaker announces, “Evil has come to my dream,” after which a female presence instructs them to undress and return to bed where they embrace. Other poems suggest the speaker is themself a dream, conjured by a stone or a stone moon, or a person falls asleep in broad daylight, searching for a missive in the world of sleep. The space between dreamer and reverie is not simply porous or overlapping: it is all-encompassing, cavernous, dissolving into the ache of the unknown.

The female presence in the dreams, waking life, and spaces in between appears to be a lover, the mother of the speaker’s child—or perhaps many lovers, or many mothers—but also an anonymous, distant figure(s) who seems to be on a parallel yet displaced wavelength from the speaker. The speaker seems to be in constant dialogue with this presence and others like it, and even when those energies are absent from the poem’s scene, the speaker continues evoking, recalling, and defying them. Herein is the brilliance of Wójcik-Leese’s translation that melds this shadowy feminine presence with that eternal, ever-present mystery: Death.

One poem in particular showcases the paradox of having a relationship with that mystery. “Posthumous correspondence” (Korespondencja pośmiertna) takes the shape of a stage or screenplay script in which a Man dialogues with Death. Glancing on the left side of the page at the Polish, I observed that the poem followed a different structure, without the character/dialogue formatting.

Curious about this choice, I reached out to Wójcik-Leese, who explained that in Polish, death is grammatically feminine, and so verb endings signifying grammatic gender reveal which passages are spoken by Death and which passages are uttered by the other person. In their translation collaboration, Świetlicki suggested pointing out the different speakers in the exchange, which resulted in a fascinating version of the original poem in English. Both correspondents seem to be speaking aloud (as if in a script), but the framework of the text is as a letter. The reader feels the conflict and contradictions of their communication—not merely between speakers and what they speak of, but how they speak to each other and the plaintive rhythm of their exchange.

Towards the end of the collection, the poems become sparser, more like jottings and diary entries. It’s as if the narrator is integrating the past, musing over the present and future, where “Plastic soldiers utter their war cries” in the ironically titled, “First poem” which is the third to last in the volume. Maybe this is the first poem for a new world or worlds, a transition point for more. It’s significant that Świetlicki has written thirteen books of poetry and that Night truck driver is the first English language collection in his work, which Wójcik-Leese notes in the translator’s afterword “follows the chronology of his poetic life and the lives of his individual volumes.” One hopes that more translations will come, as Świetlicki and Wójcik-Leese capture so hauntingly and precisely the cold ache of being called—and caught—among many worlds.

Radio Interview with Trafika Europe where you can hear Elżbieta Wójcik-Leese read the poems in Polish and English.

Reviewer Amanda L. Andrei is a Filipina Romanian American playwright, literary translator, and teaching artist residing in Los Angeles by way of Virginia/Washington DC. She writes epic, irreverent plays that center the concealed, wounded places of history and societies from the perspectives of diasporic Filipina women, and she translates from Romanian and Filipino to English. For more information on her work and upcoming events, visit: www.AmandaLAndrei.com

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs, as well as our mission to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!