Review: Night truck driver

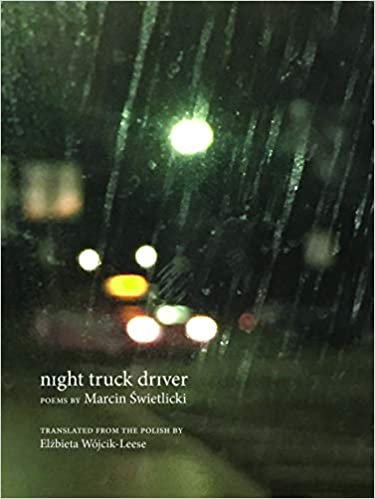

Night truck driver, By Marcin Świetlicki

Translated from Polish by Elżbieta Wójcik-Leese

Poetry

ISBN 9781938890802

128 pages

Bilingual: Polish and English on facing pages

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

The world drips. Caught in some kind of thaw, circling a winter on the verge of melting into a dream, or a dream solidifying into a cold city, Marcin Świetlicki’s Night truck driver (Kierowca nocnej ciężarówki) translated by Elżbieta Wójcik-Leese, immerses us into icy, hypnopompic places where we can hear Death and other unseen forces calling to us—and maybe even respond to them.

The opening poem, “Preface,” invokes the biblical origins of Genesis, reset in 1960s Poland: a man, a woman, a snake, but also “a stupid apple tree,” “depots, dead buses. / Old lemonade bottles of that unusual shape.” Here are seeds of Świetlicki’s themes: an overpowering sense of menace between sleep and waking, entanglements between the masculine and feminine beyond mere mortals, set among noirish urban landscapes and frosty worlds. The final line, “We’ll be observing the advance of darkness” sets up the reader for the opaque stillness at the heart of winter, questioning what life, if any, remains beneath the cold.

“Everything drips” follows immediately with an imperative, or maybe even a plea: “Don’t come into my dreams, don’t. In one dream / drown for good and don’t show up in any other.” To whom is the speaker addressing? A relative, a lover, a stranger, a monster? The ambiguity of other people’s presences in this poem and others compounds the sense of unease, giving you the sense of a faintly remembered nightmare just out of reach, or a stranger passing by your unlit house. Later on, in “Saturday, an impulse” the speaker announces, “Evil has come to my dream,” after which a female presence instructs them to undress and return to bed where they embrace. Other poems suggest the speaker is themself a dream, conjured by a stone or a stone moon, or a person falls asleep in broad daylight, searching for a missive in the world of sleep. The space between dreamer and reverie is not simply porous or overlapping: it is all-encompassing, cavernous, dissolving into the ache of the unknown.

The female presence in the dreams, waking life, and spaces in between appears to be a lover, the mother of the speaker’s child—or perhaps many lovers, or many mothers—but also an anonymous, distant figure(s) who seems to be on a parallel yet displaced wavelength from the speaker. The speaker seems to be in constant dialogue with this presence and others like it, and even when those energies are absent from the poem’s scene, the speaker continues evoking, recalling, and defying them. Herein is the brilliance of Wójcik-Leese’s translation that melds this shadowy feminine presence with that eternal, ever-present mystery: Death.

One poem in particular showcases the paradox of having a relationship with that mystery. “Posthumous correspondence” (Korespondencja pośmiertna) takes the shape of a stage or screenplay script in which a Man dialogues with Death. Glancing on the left side of the page at the Polish, I observed that the poem followed a different structure, without the character/dialogue formatting.

Curious about this choice, I reached out to Wójcik-Leese, who explained that in Polish, death is grammatically feminine, and so verb endings signifying grammatic gender reveal which passages are spoken by Death and which passages are uttered by the other person. In their translation collaboration, Świetlicki suggested pointing out the different speakers in the exchange, which resulted in a fascinating version of the original poem in English. Both correspondents seem to be speaking aloud (as if in a script), but the framework of the text is as a letter. The reader feels the conflict and contradictions of their communication—not merely between speakers and what they speak of, but how they speak to each other and the plaintive rhythm of their exchange.

Towards the end of the collection, the poems become sparser, more like jottings and diary entries. It’s as if the narrator is integrating the past, musing over the present and future, where “Plastic soldiers utter their war cries” in the ironically titled, “First poem” which is the third to last in the volume. Maybe this is the first poem for a new world or worlds, a transition point for more. It’s significant that Świetlicki has written thirteen books of poetry and that Night truck driver is the first English language collection in his work, which Wójcik-Leese notes in the translator’s afterword “follows the chronology of his poetic life and the lives of his individual volumes.” One hopes that more translations will come, as Świetlicki and Wójcik-Leese capture so hauntingly and precisely the cold ache of being called—and caught—among many worlds.

Radio Interview with Trafika Europe where you can hear Elżbieta Wójcik-Leese read the poems in Polish and English.

Reviewer Amanda L. Andrei is a Filipina Romanian American playwright, literary translator, and teaching artist residing in Los Angeles by way of Virginia/Washington DC. She writes epic, irreverent plays that center the concealed, wounded places of history and societies from the perspectives of diasporic Filipina women, and she translates from Romanian and Filipino to English. For more information on her work and upcoming events, visit: www.AmandaLAndrei.com

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs, as well as our mission to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!