Review: “Bounds” and “I Want a Country”

| Location | 2525 Michigan Ave., Building T1, Santa Monica, CA 90404 |

| Theater | City Garage at Bergamot Station |

| Date of Performance | February 7, 2025 and February 9, 2025 |

| Language(s) | English (translated from Italian and Greek, respectively) |

| Photos by | Paul M. Rubenstein |

Reviewed by Allie Rigby

Where do you go when your country has dissolved or fallen apart? What opportunities and purgatories await displaced people who have risked everything for a chance at a better life?

This weekend, two plays opened at City Garage Theatre, both with painfully relevant themes exploring what it means to leave one country forever–or consider leaving it–only to land in a disorienting, dangerous place where arriving becomes an impossible feat.

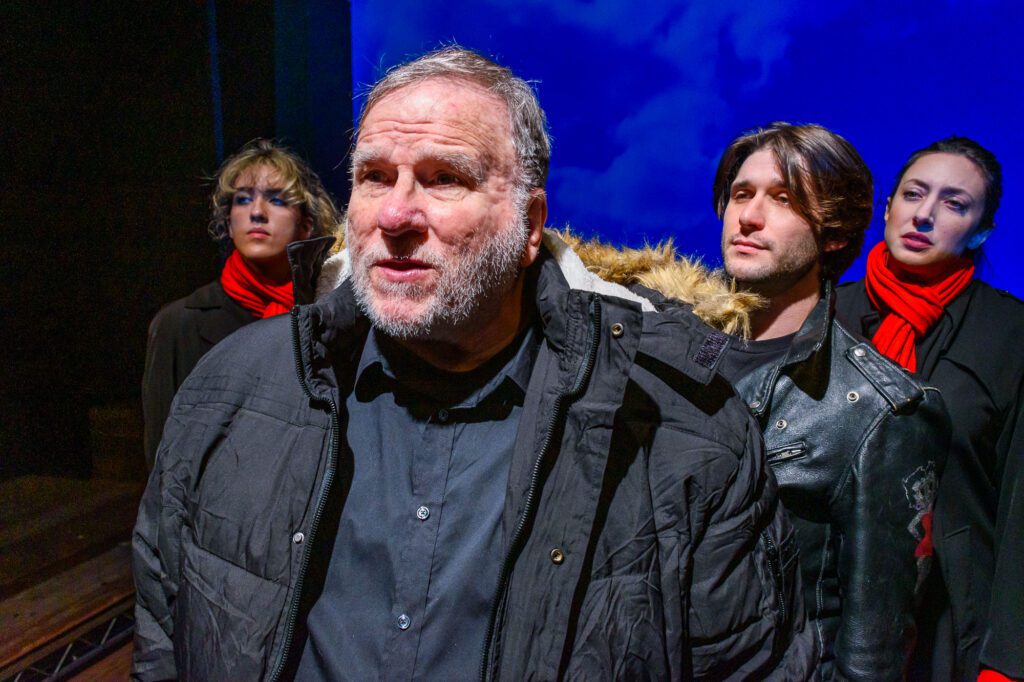

In this production of Bounds by playwright Tino Caspanello from Italy, and translated by Haun Saussy, five women in matching black outfits command the stage, collectively passing the time on the beach with conversation, dancing, fights, and childlike games with high stakes. The play opens with Woman 1 (Lenka Janischova Shockley) kneeling center stage, wishing for the comfort of a chair, which we later learn she does not have because she lost the most recent round of musical chairs.

Shockley delivers in this role, with her character often challenging the social hierarchy established in this liminal place, with its pecking order led by Woman A (Angela Beyer), and loosely reaffirmed by Woman C (Devin Davis-Lorton) and Woman B (Alyssa Frey). Meanwhile, Woman 2 (Alyssa Ross) seems aware that like Woman 1, her status among the group is not secure, and she may be the one sent back home.

Janischova Shockley, and Alyssa Frey. Photo credit:

Paul M. Rubenstein.

Rules keep the group in some order and also help pass the time. By the end of the play, it remains unclear who will be sent back home, or if any of them will be allowed to enter this new country. All we know is that they are tired and they have been waiting for a long time to arrive.

Directed by Frédérique Michel and produced by Charles A. Duncombe, Bounds succeeds in conveying the uncertainty and fear that the five displaced women share, despite their differences in personality, status, dreams, and beliefs. Duncombe also achieves an uncertain, ominous atmosphere with his choice of rumbling, surveillance-type sounds (ie., helicopters hovering) that grow especially loud in the final scene, where these women await their fate in this new country.

The ending in I Want a Country is similar in that it is also ambiguous, but in a way that is more satisfying because the characters never left their “dead” country to begin with. The despondent, anticlimactic ending conveys the hopelessness of staying in a country where life has been sucked out of it. Written by playwright Andreas Flourakis from Greece during the financial crisis of 2010, and translated by Eleni Drivas, I Want a Country conveys the impossibility of shaping a new nation by consensus or democracy.

Duncan, Alyssa Ross, Liam Galaz Howard, Shane Weikel,

Angela Beyer. Front: Daniel Strausman, Alyssa Frey, Angela

Beyer. Photo credit: Paul M. Rubenstein.

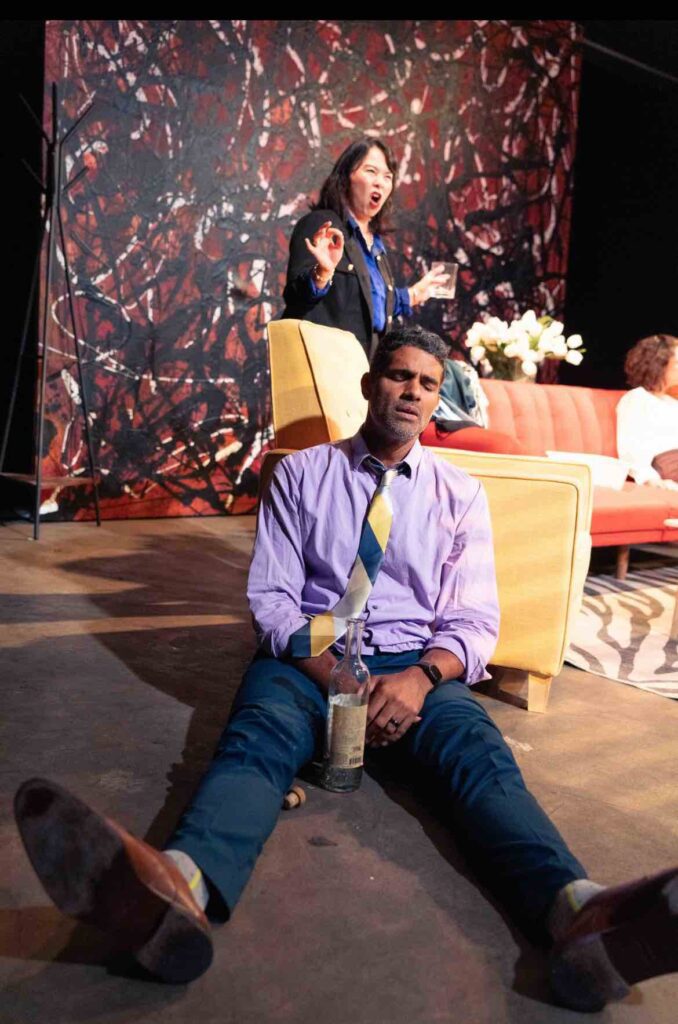

Throughout the play (also directed by Frédérique Michel and produced by Charles A. Duncombe), characters pop umbrellas to weather storms, support their partner, and carry on, but they cannot agree on much, including where to go, how a country should operate, who to welcome, who to exclude, how to make and share money, etc. A lack of money and lack of imagination are part of the problem:, the group struggles to describe a new, ideal country that does not reproduce the same ills they seek to flee.

Director Frédérique Michel adds gorgeous moments of pause, where characters freeze while doing menial tasks like tying their shoes or walking arm in arm. These glitchy, staccato moments, coupled with sequences when the characters walk backward rather than forwards, solidify a place where time is slightly warped and characters are stuck with indecision around where to go and how to make the next place better. Duncombe’s use of a didgeridoo as part of the sonic atmosphere adds a heavy, pulsating layer to these sequences where the characters are stuck in limbo.

Perhaps most memorable is Papa Escargot (Andy Kallok) whose feelings of hopelessness are palpable beginning from the moment he enters the stage, stumbles upon a pair of discarded shoes, and slumps over, exhausted, sitting on his suitcase.

Photo credit: Paul M. Rubenstein.

There are also fantastic lines throughout, such as when Storm (Daniel Strausman) gets frustrated at the group’s return to money as the solution to all their problems, saying:

STORM: “Come on guys, we’re talking about doing something revolutionary, and again the conversation goes back to money.”

TOMY: “It’s hard not to.”

LONELY: “Force of habit.”

TOMY: “We don’t just need a new country — we need a new way of thinking.”

This new way of thinking may still be what we need here in the United States too. Both of these plays are timely, especially amidst the rising threats of mass deportations of immigrants, unreasonable searches and incarcerations, and increasingly militarized borders.

Once again, and per their thirty-five year record, City Garage Theatre has produced plays that speak to the times and encourage people to have empathy and compassion for what it means to arrive in a country that may pummel you into the ground.

As Woman 1 says in Bounds,

“This whole thing is . . . inhuman.”

The plays will run in repertory, with Bounds Thursdays and Fridays, and I Want a Country on Saturdays and Sundays until March 16.

Allie Rigby is a poet, editor, and reviewer with roots in Orange County, California. She is the author of Moonscape for a Child (Bored Wolves, 2024) and the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship to Romania, where she taught creative writing at Universitatea Ovidius din Constanța. She holds a master’s degree in English: Creative Writing from San Francisco State University. She enjoys connecting with people to develop and share stories that generate cross-cultural dialogue, solidarity, and change. For more of her work and upcoming events, visit www.allierigby.com or @allie.j.rigby.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Review: The Seagull

| Location | 2055 S Sepulveda Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90025 |

| Theater | The Odyssey Theatre, Los Angeles |

| Date of Performance | January 18, 2025 |

| Language(s) | English (translated from Russian) |

| Photos by | Sasha Dawson and Miguel Perez |

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

“We need new forms,” declares Konstantin Treplev, a fledgling playwright and son of an aging actress, of the theatre. “New forms are needed, and if we can’t have them, then we had better have nothing at all.” It’s also through old forms, such as Anton Chekov’s comedy The Seagull, that audience members can contemplate the role of artists and the snares of love. Although Odyssey Theatre Ensemble’s vision of this play contains stylistic twists which belie Chekov’s realism and create an undercurrent of dissonance, the poised portrayals of the iconic Boris Trigorin and Irina Arkadina bolster the tragicomedy.

Dramatist and author Anton Chekov penned The Seagull 130 years ago, with its premiere a year later, in 1896 at the Alexandrinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, Russia. Set in a lake house and estate in the Russian countryside in the same era, the play served as an opportunity for the turn-of-the-century audiences to see themselves reflected in stark, realistic terms: family dynamics, class differences, and love triangles during a shimmery summer and then two years later, in a thunderstorm.

There’s Irina Arkadina (Sasha Alexander), a theatre actress trying to reclaim her youth and influence, visiting her brother Pyotr Sorin (Joe Hulser), retired official and owner of the lake house. Her son Konstantin (Parker Sack), living under the shadow of his mother and aspiring to be a writer. Boris Trigorin (James Tupper), established writer and paramour of Irina, who falls for the 19-year-old idealistic Nina Zarechnaya (Cece Kelly), a neighbor to the estate who longs to be an actress and in the world of theatre and literati. And then there are multiple other guests, neighbors, and servants who add to the rich texture and intrigue of Russian society.

It would be easy to paint Trigorin as a slimy creep, preying on a teenage Nina for his own base desires and insecurities. But James Tupper is exquisite, inhabiting the role with such innocent presence and care that it’s easy to be seduced by—and sympathetic towards—this romantic writer. Sasha Alexander also fills her Irina with vigor and desperation, drawing bursts of laughter with her comedic timing and commanding rapt attention as she baits Trigorin to return to her arms. Parker Sack as Konstantin offers boyish rebellion, optimism, and moodiness—he shines best during a verbal throwdown with his rapacious mother—though witnessing a more transformative arc towards the end would have been more satisfying and poignant. Performances by Will Dixon as Dr. Dorn, and Carlos Carrasco as the steward Shamrayev, are also notable for the gusto and enthusiasm they bring to these side characters.

by the lake. Photo credit: Miguel Perez.

Part of the trouble with this production is that some of the visual stylistic choices conflict with the realism and era invoked from the text, a translation from 1960 by Ann Dunnigan. The translation itself is clear, and occasionally feels dated with its exclamations and endearments (“Fiddlesticks!” “Little one!”), but the dated feeling seems to come more from the ambiguity around time and place within the production. It’s unclear what the time period is: costumes and props verge on the modern, and small details like sunglasses, a camouflage outfit, and a ballpoint pen impart anachronistic touches that distract. The sprawling moss and large aquamarine lake in the background (cleverly designed by Carlo Maghirang) evoke feelings of immersivity and stagnancy beneath beauty, but also give an expressionistic feeling, as if the house and action symbolically live within the lake, instead of alongside it.

Director Bruce Katzman also crafts some moments of characters freezing in charged moments, creating silent tableaus that adds a touch of strangeness to the production. The choice to get playful and more abstract with The Seagull is a noteworthy one, though it seems the production would benefit from a more modern or updated translation that would allow the creative team to be more flexible with the contemporary design choices and have a more unified vision.

Given the situation with the wildfires, it can be jarring to return to the theatres during this time in L.A. Chekov’s summer vacation world and love entanglements seem far removed from the disaster befalling the City of Angels. But in fact, they hearken to L.A. as the illusory La-la-land, that amidst the luster of the entertainment industry, there are scores of individuals who are dreaming, scheming, and hustling to make a life in the arts. Some motives may be naïve or petty, others heartfelt and sincere.

As Nina tells Konstantin towards the end, after her share of trials and heartbreak,

“I know now, I understand, that in our work, Kostya—whether it’s acting or writing—what’s important is not fame, not glory, not things I used to dream of, but the ability to endure.”

In this time, that endurance is a reminder for every Angeleno.

Cristina Sandu Bio: Journalist Cristina-Ioana Sandu graduated from De Montfort University in the UK and is passionate about photography, cinema, music, and storytelling. With a background rooted in journalism and media, Cristina brings a vibrant perspective to her work, shaped by hands-on experience in the film industry and live event production.

Her journey also includes crafting compelling narratives that explore identity, art, and human connection. Her blog acts as a personal and creative space to document life, celebrate authenticity, and highlight significant voices in arts and culture. Discover more at: www.cristinaioanasandu.com

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Review: God of Carnage

| Location | 905 Cole Theatre @ Anthony Meindl’s Actor Workshop – 905 Cole Ave, Los Angeles, CA 90038 |

| Theater | Thunderbird Garage Productions, Los Angeles |

| Date of Performance | September 15, 2024 |

| Language(s) | English (translated from French) |

| Photos by | Zadran Wali |

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

Ah, modern-day parenting. Caring for children and pets, maintaining a household, negotiating politely with other stressed parents about whose child hit who and how and why and what the consequences will be… beneath the surface of civilized life, Yasmin Reza’s God of Carnage portrays the absurdity and anger between two pairs of parents dealing with a physical altercation between their children.

Le Dieu du Carnage originally premiered in Zurich in 2006. Later translated from French into English by Christopher Hampton, God of Carnage and its translations have had multiple productions around the world. The English translation, set in Brooklyn instead of Paris, opened on Broadway in 2009, and the story was adapted into a film, Carnage, which premiered in 2011 and was directed by Roman Polanski. Thunderbird Garage Productions remounts the play in the intimacy of a small L.A. theatre, dousing us in the agitation and discomfited humor of upper middle-class parents.

In the play, Michael (Eric Larson) and Veronica (Olga Konstantulakis) cordially host Alan (Kristian Kordula) and Annette (Andrea Lwin)–the parents of a boy who has just injured their son. Over espresso, clafouti, and verbal niceties, they gradually descend into shambles as their prejudices and judgmental behaviors are exposed. Under Kim Quinn’s direction, frustration and anger prevail at an intense volume, at times overpowering portrayals of disgust, resentment, and shock. The fury is more apt when dialogue explodes into action—Konstantulakis displays splendid rage when she pummels her husband, as does Lwin when she wreaks havoc on her husband’s phone. Kordula and Larson likewise draw laughs from the audience with their comedic timing and well-placed silences, adding sardonic texture to the baseline of ire.

The set is simple yet detail-oriented (built by Eric Larson), with modern art sculptures delineating the room and a massive black, white, and maroon abstract painting reflecting the characters’ collective internal chaos. Jacob Nguyen’s lighting design subtly tracks the realistic time of the play through Venetian blind shadows, while his pre-show and post-show music evokes the friction between modern day expectations and more subconscious forces at play.

Created by four friends from Larry Moss acting workshops, this show marks Thunderbird Garage’s first production. Though there’s room for more emotional nuance in the characters’ journeys, it’s a treat to see a contemporary classic staged with such spirited earnestness.

“Men are so wedded to their gadgets,” fusses Annette, “It belittles them.” An evening with carnage should help with that.

Cristina Sandu Bio: Journalist Cristina-Ioana Sandu graduated from De Montfort University in the UK and is passionate about photography, cinema, music, and storytelling. With a background rooted in journalism and media, Cristina brings a vibrant perspective to her work, shaped by hands-on experience in the film industry and live event production.

Her journey also includes crafting compelling narratives that explore identity, art, and human connection. Her blog acts as a personal and creative space to document life, celebrate authenticity, and highlight significant voices in arts and culture. Discover more at: www.cristinaioanasandu.com

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Review: Stalin’s Master Class

| Location | Odyssey Theater, Los Angeles, CA |

| Date of Performance | June 2, 2024 |

| Language(s) | English |

| Photos by Jenny Graham | Amanda L. Andrei |

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

A kick to a cane and a man falls to his knees. A command to sing and fear fills the singers’ eyes. These small cruelties inhabit the spacious room of Stalin’s Master Class as the full terror of the regime stays subdued.

The lion’s share of danger resides with the historical figure of Josef Stalin, the Georgian dictator responsible for the deaths of millions across Eastern Europe as he consolidated power into the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR or Soviet Union), a world superpower from 1922 to 1991. By the time this play was written in 1984 by British playwright David Pownall, the dictator had been dead for thirty years, the Soviet Union was entering an era of decline, and Cold War tension ran high with nuclear threat.

Odyssey Theatre’s restaging of this satirical drama is a fascinating choice for 2024, as the memory of Stalin has faded, but global concerns over authoritarianism and populism remain high.

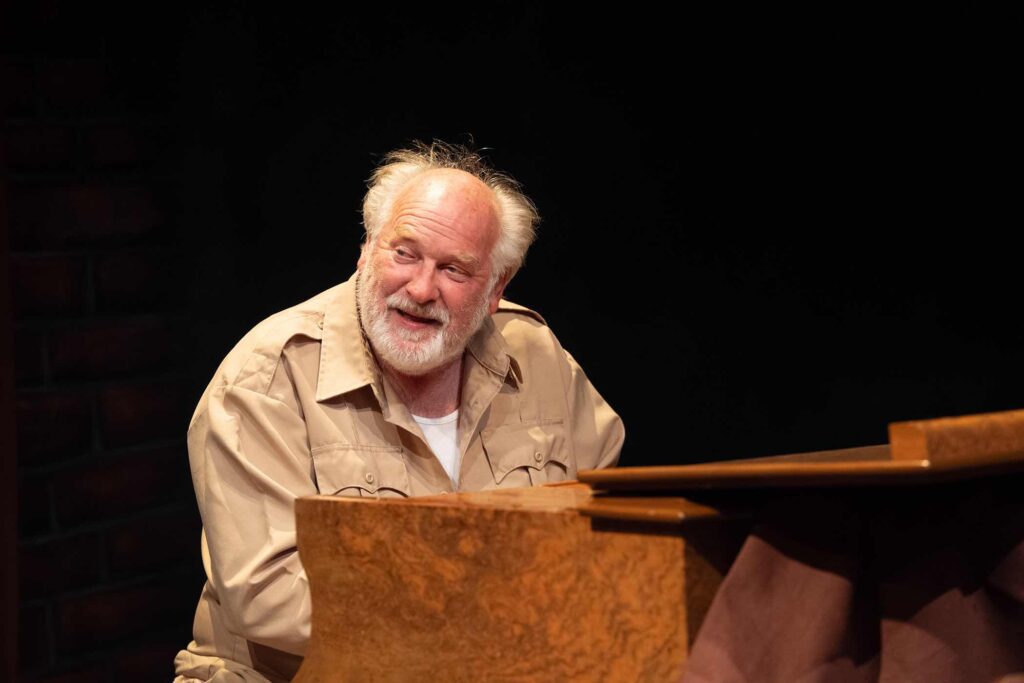

Based on events from a musician’s conference in January 1948 at the Kremlin, where Secretary of the Communist Party Andrei Zhdanov summoned musicians and music critics to deride their aesthetics and adherence to formalism, Stalin’s Master Class extends and fictionalizes the scenario further. Zhdanov (John Kayton) invites two composers, Dmitri Shostakovich (Randy Lowell) and Sergei Prokofiev (Jan Monroe), to a private audience with Stalin (Ilia Volok) at the Kremlin. And an invitation from an autocrat is never just an invitation.

In this case, the invitation meanders between philosophizing about the relationships between high and folk art, playing piano under threat, and eventually forcing a nightmarish creative jam session in an attempt to create a new Soviet culture. Director Ron Sossi finds the comic absurdist moments amidst the political palaver, revealing the true-to-life incongruity of regimes bent on hammering the arts into their agendas–and the awkward and soul-crushing failures that result. Dark crimson and iron reds in the plush furniture, sizable curtains, and a priceless icon (scenic designer Pete Hickok and prop designer Jenine Macdonald) likewise reflect the tension of an authority striving to maintain social realism while tempted by the bourgeoisie and royal taste.

John Kayton’s Zhdanov lives in this world of social realism and pragmatism, radiating his disgust with the composers in every shot of vodka he takes. Randy Lowell (as Dmitri Shostakovich) and Jan Munroe (as Sergei Prokofiev) portray artists under pressure with rapt silences and careful rebuttals, aware that they could be exiled at any moment. Relief blooms in the room when any of them sit at the piano to play—musical direction by Nisha Sujatha Arunasalam transforms their abstract discussions into emotion when they strike the keys.

It’s also noteworthy that offstage, Arunasalam plays the majority of the songs beautifully (alternating with pianist Michael Redfield, and with Lowell gracefully playing the Shostakovich sections).

The standout of this performance is Ilia Volok as Stalin. Humanizing a dictator is tricky territory, as it runs the risk of absolving a ruler of past atrocities that still haunt people and nations in the present. With an erratic mix of warmth, aggression, and stillness, Volok masterfully inhabits the despot with the cunningness and unpredictability of a coiled tiger, ready to strike the musicians at any moment. Neither absolved nor indicted, Volok’s Stalin—even in his most sympathetic moments—serves as a cruel and capricious symbol brought to life.

If only Pownall had written the musicians with more fear injected into them. Their trepidation remains mostly interior, save for an odd plot point where Shostakovich goes to a side bathroom and wills himself aloud to survive—then returns into the main room and uncharacteristically picks up the icon that had previously been mocked.

The imbalance of power—and the means of demonstrating it mostly through conversation—eases the sense of danger and real violence that the dictator could inflict upon the composers. Additionally, while it doesn’t happen often, some of the actors’ Eastern European accents slip into American ones, breaking the illusion of their characters. During intermission, and as I left the theater, I heard slivers of conversation about Putin, Ukraine, and world wars. It’s not merely Cold War shadows that still haunt us–It’s the ghosts of the current war. And as long as history keeps repeating itself, it seems that Stalin’s Master Class will keep enrolling.

Cristina Sandu Bio: Journalist Cristina-Ioana Sandu graduated from De Montfort University in the UK and is passionate about photography, cinema, music, and storytelling. With a background rooted in journalism and media, Cristina brings a vibrant perspective to her work, shaped by hands-on experience in the film industry and live event production.

Her journey also includes crafting compelling narratives that explore identity, art, and human connection. Her blog acts as a personal and creative space to document life, celebrate authenticity, and highlight significant voices in arts and culture. Discover more at: www.cristinaioanasandu.com

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Review: Trio. For the beauty of it

| Location | Goose on a String Theatre / Provazek hall in Brno, Czech Republic |

| Date of Performance | May 23, 2024 |

| Language(s) | English, French, and Spanish |

| Photos by Ivo Dvořák | Alex Mugler |

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

Poisson. Head bob. Poisson. Head bob. Je suis. Hand-chest. Je suis. Hand-chest.

In a simple rhythm, a pair of dancers build gestural language: one speaks into a microphone far downstage, almost in the audience, and the other waits in the center, associating a body motion with the spoken word. As “poisson” (French for “fish”) becomes a dip of the head, other words in French and English follow suit throughout Trio. For the beauty of it. The three dancers of the transnational company La Fleur use spoken language only to transcend speech, all while deftly unveiling their creative process to the audience and celebrating their heritage dance styles.

Director Monika Gintersdorfer and choreographer Franck Edmond Yao, both co-founders of La Fleur, conjure an ingenious space for each dancer to shine individually as well as an ensemble.

The Ivorian choreographer and dancer Ordinateur rises first with coupé-décalé, a style of dance and music originating from the Ivorian diaspora in Paris in the early 2000s. He vibrates with atomic essence, the repetition and speed of his steps so simple and precise that the effect is trancelike. Speaking in French, the dancer also tells us that in Côte d’Ivoire, the slang for this dance is “roukasskass,” a word both crunchy and sibilant that feels in line with the swift drumbeats and Ordinateur’s footsteps.

Carlos Gabriel Martínez Veláquez shakes us into cumbia sonidera, a Mexican subgenre of cumbia, a DJ-influenced music and dance style with roots in Latin American and African traditions. To the sounds of salsa guitar licks with an electronica touch, Veláquez spins and quakes with abandon, drawing in the other dancers.

Switching between English and Spanish, the dancer also generously shares meanings of the symbols behind his cultural and artistic influences. Most striking is the idea of the snake, which he tells the audience, “The snake helps us do the right thing in the right moment in the right mode.” In the midst of such festivities, it’s a beautiful reflective moment of how a dancer intuits their next move, how the animal and the divine are present as a source of grace, awareness, and eroticism.

Repping the New York vogue and ballroom scene, Alex Mugler shares with us the dance style developed by queer black and Latine folks of color from the 1960s and onwards in Harlem. With confidence and poise, Mugler’s hands and arms swoop, dive, and flourish before he leaps to the floor, nimbly twisting and posing to loud cheers.

His performance of a song about “kiki”—a slang term from ballroom culture that can refer to the giddiness of a friends’ gossip circle—provides a ticklish moment with a deeper meaning. As the three dancers weave in and out of each other’s space, reciting opposites such as “up, down, right, left,” Mugler sings variations of “let’s have a kiki.” It’s as breezy and fun as spilling tea tends to be, but it also serves as a subtle approach to breaking binaries: we can interrupt our notions of dualism and black-and-white thinking with the frivolity and mercurialness, letting us view the world with more fun and ease.

Towards the end of the hour, Mugler leads Ordinateur and Veláquez in a ballroom dance-off, telling us that we get to judge their skills. It’s another act of generosity to invite us into this world, and we roar with praise for the dancers—who then invite us onstage to romp and whirl with them. And when dancers this skillful encourage you to play and move with them, there’s no hesitation. You dance for the beauty of it.

More information about the Theatre World Brno 2024 Festival (May 17-28) is available here.

Cristina Sandu Bio: Journalist Cristina-Ioana Sandu graduated from De Montfort University in the UK and is passionate about photography, cinema, music, and storytelling. With a background rooted in journalism and media, Cristina brings a vibrant perspective to her work, shaped by hands-on experience in the film industry and live event production.

Her journey also includes crafting compelling narratives that explore identity, art, and human connection. Her blog acts as a personal and creative space to document life, celebrate authenticity, and highlight significant voices in arts and culture. Discover more at: www.cristinaioanasandu.com

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Review: The Ratcatcher

| Location | Radost Theatre in Brno, Czech Republic |

| Date of Performance | May 22, 2024 |

| Language | Czech with English language surtitles |

| Photo by Jakub Jíra | Jiří Skovajsa as Pied Piper. |

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

Once upon a time, there was a small German town named Hamelin. When it became plagued by rats, the mayor sought to eliminate the pests, using cats, traps, and poison. Naturally, when these methods didn’t work, he called in the heavyweight hotshot: a skull-faced Mickey Mouse toting an empty sack and playing a mean recorder.

That’s The Ratcatcher, a clever and intricate adaptation of the Pied Piper fairytale for ages 12 and up, produced by Divadlo Radost in cooperation with the French puppet company, Les Antliaclastes. Performed at the Theatre World Brno Festival, the story expands upon the original folktale with kooky, lush detail and a modern twist.

Early on, the rats emerge from a massive dollhouse-like structure that doubles as the Hamelin neighborhood (designed by Patrick Sims, also director and puppeteer). Each compartment resembles a shadow box: some with miniature furniture, some with musical instruments, some simply plain with wallpaper or a human doll. There’s even a toilet with a cross-section of piping running down the side. The set’s playfulness contrasts against the sinister nature of a huge disease-ridden flea (played by Radim Sasínek) and the crafty mayor (Václav Vítek), each donning superb masks designed by Josephine Biereye.

But their sinister nature pales in comparison to the creepiness of the pied piper (Jiří Skovajsa), emanating cutthroat business ideals and greed. In the guise of the notorious Mouse and the specter of Death, he wears a jingling coat of suit ties and seduces the rats (and later, the children) with his music until they plop into his cloth sack and the musical mercenary hopes coins will fill his hand. On their way to death? As a modern fairytale crustacean would croon, “They in for a worser fate.”

As the friendly Rat Girl (Stanislava Havelková) cracks open the house-town with a wooden spoon, the German legend catapults into the satirical sci-fi world of Hamelin Laboratories, where the traitorous mayor—now referred to as Research Director—conducts bizarre experiments on rats and humans.

The exaggerated nature of the puppets (including a robotic feline and a chatty cheese wedge) keep the circumstances comic and cartoonish. Whereas older endings of the narrative focused on disability, death, or despair, Les Antliaclastes and Divadlo Radost take anxieties about the future and present them in a style that is refreshingly weird, thanks to its mashup of fairytale and mad science gone corporate.

There are a few opportunities for growth in the show. For instance, the bit of one rat turning rockstar is so amusing that it deserves an encore. And when the masked Rat Girl plays with unclothed baby dolls from a carriage, it’s unclear if they’re meant to represent living children or everyday toys, making it difficult to establish a sense of attachment for the figurines or their connections to the kidnapped children. These are minor details in an otherwise sensory-rich production and one aimed at adolescents.

The concept could go the direction of George Orwell’s Animal Farm if the company so desired, transforming into a sharp fable about current economic and social conditions. But with a traditional tale already so piercingly macabre, and a Hamelin house-town-lab so lavishly constructed, sharp edges aren’t necessary to enhance the show’s quaint delight. Skeleton Mickey is plenty.

More information about the Theatre World Brno 2024 Festival (May 17-28) is available here.

Cristina Sandu Bio: Journalist Cristina-Ioana Sandu graduated from De Montfort University in the UK and is passionate about photography, cinema, music, and storytelling. With a background rooted in journalism and media, Cristina brings a vibrant perspective to her work, shaped by hands-on experience in the film industry and live event production.

Her journey also includes crafting compelling narratives that explore identity, art, and human connection. Her blog acts as a personal and creative space to document life, celebrate authenticity, and highlight significant voices in arts and culture. Discover more at: www.cristinaioanasandu.com

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!