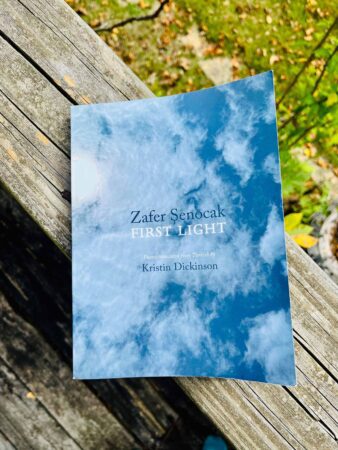

Review: First Light by Zafer Şenocak

| Author | Zafer Şenocak |

| Translated By | Kristin Dickinson |

| Genre | Poetry |

| Language(s) | Turkish, English |

| Format | 160 Pages |

| Publisher | Zephyr Press |

| ISBN | 978-1-938890-30-7 |

Reviewed by Allie Rigby

What does it mean to exist in one place, physically, but mentally and emotionally exist elsewhere, simultaneously suspended in past, present, and future? Such time-warped entanglement ricochets throughout Zafer Şenocak’s bilingual poetry collection, First Light, translated from Turkish into English by Kristin Dickinson (Zephyr Press, 2024).

Many of the poems speak to the ideas of memory, language, and home, home being an ethereal concept often–if not ever so slightly–out of reach; accessible in wisps, dreams, and impressions that linger as briefly as morning light.

Şenocak’s poems ache with longing and acknowledgments of human contradictions. The original poem unfolds on the left page, in Turkish, and on the right lays the English translation.

In the poem, Muammaydun or I was a riddle (pg. 68-69), the speaker’s voice aches with loneliness and the universal desire to be known:

“I didn’t want to be an I

I wanted there to be someone

Yearning for me

My faithful companion

When you reach me

Let me be known” (Lines 16-21).

The “you” is an especially compelling address in this poem and throughout the collection. Is “you” a lover? The reader? A deeper, spiritual companion? The “cosmos” as Dickinson writes in the opening text “Unraveling the Self in Translation”? All of the above? With the “you” address, readers are brought into an intimate conversation between the speaker and someone. How readers interpret the “you” will influence each subsequent reading of the poem. But rather than get too stuck on who this “you” may be, I ask myself what the poet Brynn Saito encourages her students to ask themselves, when reading a poem for the first few times: how does the poem make me feel?

After reading I was a riddle I initially felt soothed by the longings I shared with the speaker; I also felt forlorn that loneliness was so inevitable. The repetition of “I” in Line 16 has a sense of contraction in itself–only through the “I” can the speaker express who they do and don’t want to be, and how to break free of the loneliness of the singular “I” is simultaneously impossible and desired.

The last two lines provide the solace, the hope, that someone, or something, will enter the speaker’s life and see them truly. Does this happen at death? Or before, via spiritual companionship? Or perhaps with deep friendship? Like many poets whose writing I admire, Şenocak does not answer it explicitly, but rather, lets us revel–and struggle–with the questions.

It’s impossible to ignore the role of language in any work of translation. Those who are familiar with Şenocak’s impressive canon of work, which according to his bio on Zephyr Press, includes “ten books of poetry, seven novels, and five essay collections” may know that he wrote much of his earlier work in German first, rather than in Turkish. Zephyr Press published Door Languages in 2008, which Şenocak wrote in German and Elizabeth Oehlkers Wright translated into English. First Light was written in Turkish first, as is much of Şenocak’s recent work. Translation is an art and an interpretation, the initial language of a text will influence the subsequent translations.

The relationship between language and home is deeply intertwined in this collection. In Kalbini üzme or Don’t trouble your heart (pg. 30-31), the poem flows from the title as:

“May the dust surrounding it

Never tire you

Neither home nor homesickness will come of that dust

You’ve tried enough

To make a home at the water’s edge” (Lines 1-5).

What troubles the speaker here is not the inevitability that dust falls around the heart, but rather the exhaustion that comes from this dust. There is a gentle acceptance in this address, an invitation to imagine a different kind of home: whatever actions the addressed “you” has made to make a home have not succeeded. The rich image of making a home at the water’s edge is once again soothing and promising, and yet, the speaker here reminds the “you” that they can pause that home-making attempt.

What then, does it mean, to forgo making a home? Or is home not a physical thing to make, but only possible in the form of language, itself? To be at home in language.

To–as Şenocak closes that poem–“Let the knots in your throat open.” Each poem then, an experiment into untying more of the ropes that bind us.

Allie Rigby is a poet, editor, and reviewer with roots in Orange County, California. She is the author of Moonscape for a Child (Bored Wolves, 2024) and the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship to Romania, where she taught creative writing at Universitatea Ovidius din Constanța. She holds a master’s degree in English: Creative Writing from San Francisco State University. She enjoys connecting with people to develop and share stories that generate cross-cultural dialogue, solidarity, and change. For more of her work and upcoming events, visit www.allierigby.com or @allie.j.rigby.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

Göbeklitepe- The World’s First Temple

12,000 years ago, the world’s first temple, Göbeklitepe, was built near Urfa in Turkey.

Massive carved stones were arranged in rings by prehistoric people who had not yet developed metal tools. The stones are covered in carvings of foxes, lions, vultures, and scorpions using only stone hammers and blades. The tallest pillar is 16 feet and the site pre-dates Stonehenge by 6,000 years.

Massive carved stones were arranged in rings by prehistoric people who had not yet developed metal tools. The stones are covered in carvings of foxes, lions, vultures, and scorpions using only stone hammers and blades. The tallest pillar is 16 feet and the site pre-dates Stonehenge by 6,000 years.

After Göbeklitepe was dismissed by many as an abandoned Medieval cemetery, German archeologist Klaus Schmidt decided to look for himself. He saw a hill with a gently rounded top and knew it had to have been man-made.

Funnily, Göbeklitepe means “potbelly hill” in Turkish. Schmidt and a team of archeologists have been excavating and analyzing the site. The site is believed to have been a social ritual gathering place attended by hunter and gatherer inhabitants.

A documentary on the Göbeklitepe is available online and has been made available for free by the filmmakers. Watch it below or you can find it on both YouTube and Vimeo.

Have you been to the Göbeklitepe site? Let us know in the comments. And, be sure to sign up to get Festival emails so you don’t miss any SEEfest events!

How to Enjoy SEEfest At Home

While the 15th South East European Film Festival is temporarily postponed, we invite you to stay in touch and enjoy some of the films from our past editions online. They are available on Netflix, Amazon, iTunes and some on YouTube (and some for free)! We’ll share updates, tips, and recommendations on Instagram at @seefest and here, on our website.

Stay safe, and we hope you enjoy our movie choices! Be sure to let us know in the comments, which films are your favorites! Check out SEEfest At Home Part 2

SARAJEVO

This lavishly produced thriller was first screened at the opening of our festival in 2014. The story is told from the point of view of the examining magistrate who was tasked with investigating the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo in June 2014. It perfectly summarized the festival’s theme, “Europe in time of turmoil”, highlighting the turbulent past that looms large over the present.

This lavishly produced thriller was first screened at the opening of our festival in 2014. The story is told from the point of view of the examining magistrate who was tasked with investigating the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo in June 2014. It perfectly summarized the festival’s theme, “Europe in time of turmoil”, highlighting the turbulent past that looms large over the present.

Directed by Andreas Prochaska. Main cast: Florian Teichtmeister, Jürgen Maurer, Melika Foroutan, Edin Hasanović.

SARAJEVO is available on Netflix.

THE WAY I SPENT THE END OF THE WORLD

Shown at SEEfest back in 2007, the film is a bitter-sweet throwback to Romania on the eve of the 1989 revolution, with ordinary people committing small and oftentimes comic acts of defiance while naively dreaming of swimming across the Danube to freedom – or fantasizing about escaping in a submarine.

Shown at SEEfest back in 2007, the film is a bitter-sweet throwback to Romania on the eve of the 1989 revolution, with ordinary people committing small and oftentimes comic acts of defiance while naively dreaming of swimming across the Danube to freedom – or fantasizing about escaping in a submarine.

Directed by Catalin Mitulescu. Main cast: Dorotheea Petre, Timotei Duma, Ionut Becheru, Jean Constantin.

THE WAY I SPENT THE END OF THE WORLD is available on Amazon Prime.

THE CONSTITUTION

The opening film of the 2017 edition of our festival. While recovering from a homophobia-driven assault, a Croatian professor confronts his own xenophobia after agreeing to help his Serbian neighbor memorize the Croatian constitution for a citizenship exam. An example of a great director-writer pairing (Rajko Grlić and Ante Tomić), this film features three amazing actors from Serbia and Croatia in a very funny and poignant ‘love story about hate.’

The opening film of the 2017 edition of our festival. While recovering from a homophobia-driven assault, a Croatian professor confronts his own xenophobia after agreeing to help his Serbian neighbor memorize the Croatian constitution for a citizenship exam. An example of a great director-writer pairing (Rajko Grlić and Ante Tomić), this film features three amazing actors from Serbia and Croatia in a very funny and poignant ‘love story about hate.’

Directed by Rajko Grlić. Main cast: Nebojša Glogovac, Ksenija Marinković, Dejan Aćimović.

THE CONSTITUTION is available on Amazon Prime.

NO MAN’S LAND

Danis Tanović’s Academy Award®-winning satire of the war in the Balkans is an astounding balancing act, an acidic black comedy grounded in the brutality and horror of war. Stuck in an abandoned trench between enemy lines, a Serb and a Bosnian play the blame game in a comic tit-for-tat struggle while a wounded Bosnian soldier lies helplessly on a land mine. A French tank unit of the U.N.’s humanitarian force (known locally as “the Smurfs”), a scheming British TV reporter, a German mine defuser, and the U.N. high command (led by a bombastically ineffectual Simon Callow) all become tangled in the chaotic rescue as the tenuous cease-fire is only a spark away from detonation. Tanovic directs with a ferocious, angry eloquence and makes his points with vivid metaphors and savage humor as harrowing as it is hilarious. Searing and smart, this satire carries an emotional recoil.– written by Sean Axmaker.

Danis Tanović’s Academy Award®-winning satire of the war in the Balkans is an astounding balancing act, an acidic black comedy grounded in the brutality and horror of war. Stuck in an abandoned trench between enemy lines, a Serb and a Bosnian play the blame game in a comic tit-for-tat struggle while a wounded Bosnian soldier lies helplessly on a land mine. A French tank unit of the U.N.’s humanitarian force (known locally as “the Smurfs”), a scheming British TV reporter, a German mine defuser, and the U.N. high command (led by a bombastically ineffectual Simon Callow) all become tangled in the chaotic rescue as the tenuous cease-fire is only a spark away from detonation. Tanovic directs with a ferocious, angry eloquence and makes his points with vivid metaphors and savage humor as harrowing as it is hilarious. Searing and smart, this satire carries an emotional recoil.– written by Sean Axmaker.

Directed by Danis Tanović. Main cast: Branko Đurić, Rene Bitorajac, Filip Šovagović. SEEfest held a special 10th-anniversary screening of the film in 2012.

NO MAN’S LAND is available on Amazon Prime.

THE EYE OF ISTANBUL

The legendary Armenian-Turkish photographer Ara Güler dedicated his life to recording the spirit of one of the most vivid cities on earth: Istanbul. Güler’s colorful life and witty commentary will keep you entertained while you discover the unforgettable vistas and rarely seen corners of the great city. The film, directed by Binnur Karaevli and Fatih Kaymak, screened at SEEfest in 2016.

The legendary Armenian-Turkish photographer Ara Güler dedicated his life to recording the spirit of one of the most vivid cities on earth: Istanbul. Güler’s colorful life and witty commentary will keep you entertained while you discover the unforgettable vistas and rarely seen corners of the great city. The film, directed by Binnur Karaevli and Fatih Kaymak, screened at SEEfest in 2016.

THE EYE OF ISTANBUL is available on iTunes/Apple, and Amazon Prime.

Become a guest curator for our online edition!

While we all need to do our part and follow the public health guidelines to keep us and others safe, shelter-in-place can be challenging. When you take a break from working remotely or get tired of binge-watching your favorite shows, join the SEEfest community of artists and create a short video, podcast, jingle or cartoon and share with us on Instagram and tag us @seefest or submit to us via the website.

SEEfest program and activities are supported, in part, by the California Arts Council, a state agency; Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles County Department of Art and Culture; and presented with the support of the City of West Hollywood. For more info on WeHo Arts programming please visit www.weho.org/arts or follow via social media @WeHoArts. Special thanks to ELMA, and the Hollywood Foreign Press Association for their continued support of our programs.

SEEfest at 15: Whose is this song?

Warning: singing can be a dangerous business! Ever since we took the road trip with Bulgarian filmmaker Adela Peeva in 2006 with her iconic film, it has been a non-stop movie travel through competing histories, similar yet antagonistic cultures, always peppered with characteristic black humor and idiosyncratic music. The Balkan Sound entertained our audiences through many more music and ethnomusic documentaries throughout SEEfest’s decade and a half.

Whose is this song? was our first opening film in 2006

And it all began with Whose is this song? in 2006, at the Goethe-Institut Los Angeles, our original home where SEEfest was welcomed and nurtured by programmer Margit Kleinman and media manager Stefan Kloo.

Nicholas Wood wrote about the film in the International Herald Tribune and mentioned some interesting details.

“The film does not attempt to define where the song originally came from, although Peeva said she was given numerous differing explanations, including the possibility that it had been introduced by soldiers from Scotland who were based in Turkey during the Crimean War.

In Greece it is known as “Apo Xeno Eopo,” or “From a foreign land,” and in Turkey it is called “Uskudar,” after the region of Istanbul.

The Turkish version was the subject of a film, “Katip” (The Clerk), directed by Ulku Erakalin in the 1960s, and the singer and actress Eartha Kitt recorded a version of the song, also called “Uskudar,” in the 1970s.”

Whose is this song? is available in the U.S. thanks to DER, Documentary Educational Resources collection in Watertown, Massachusetts. Check it out! It’s well worth it, and still very much relevant.

Whose is this song?

70 min, 2003

in Bulgarian, Turkish, Greek, Albanian, and Bosnian

with English subtitles

About the South East European Film Festival (SEEfest)

SEEfest presents cinematic and cultural diversity of South East Europe to American audiences and creates cultural connections through films, literary and art talks, retrospectives, and community events. The 15th festival will take place from April 29 to May 6, 2020.

Stay up to date with SEEfest Events and join us on our Facebook Page.