The Museum of Unconditional Surrender by Dubravka Ugrešić – Book Review

The Museum of Unconditional Surrender

Translated into English by Celia Hawkesworth

Reviewed by Natasha Ravnik

While reading Dubravka Ugrešić’s book, The Museum of Unconditional Surrender, I wondered if humankind had learned anything. Although Ugrešić wrote this work between 1991 and 1996, when her homeland of Yugoslavia was being destroyed by war, her words remain current.

There are many threads in Ugrešić’s writing that are worth exploring, but I have limited this review to just one aspect of the work: the life of the exile.

The Museum of Unconditional Surrender is unusual from the beginning: it starts with a catalogue of the contents of the stomach of Roland the Walrus in the Berlin Zoo and continues with an experimental mixture of genres. The use of narrative from various viewpoints, diary entries, and quotations parallels the recurrent fragmentation effects of trauma on the psyche – shards of not fully put back together-able language, memories, and images, bring us back to a starting point that can never be the same.

By definition, an unconditional surrender is one in which no guarantees are given to the surrendering party. It can be demanded with the threat of complete destruction, extermination, or annihilation. To what kind of life does the refugee surrender to?

“Those are all cold, melancholy, objective images (or more precisely: verbal photographs) from a past life in a former country which it will never again be possible to connect into a whole,’ writes Mihajlo P. in a letter.”

The Museum of Unconditional Surrender is a disparate archive of the bleak reality of loss as a result of forced migration. The stories within are mournfully human – they endear with their naked vulnerabilities. Displayed openly like a pack of cigarettes on a card table at a flea market are the visceral consequences of a nation’s spontaneous dissolution.

“10. ‘Refugees are divided into two categories: those who have photographs and those who have none,’ said a Bosnian, a refugee.”

With exquisitely simple sentences, Ugrešić brings out complex truths – the utter senselessness of the effects of war is tied up with a tender bow. Her prose unfurls unexpectedly like a poem, a jewel offered on a platter of tears, shiny but dissolving.

“Like the train of a gown, he dragged after him his secret, which, it seems, bore the simple name: indifference.”

Much of the narration is from a singularly feminine viewpoint ranging from a quiet melancholy,

“What a woman needs most is air and water.”

to a lonesome inevitability,

“As she crossed the Yugoslav border she was suddenly afraid, either because of the custom official’s black mustache, or the finality of her decision. And as she opened her suitcase, thinking in panic that she still had time to change her mind and go back, it slipped out of her hand and scattered its modest contents over the floor. She remembers the rolling apples (“There were lots of them, lots of apples,’ she says. ‘I don’t know myself why I had packed so many.’) Her memory was stuck on that picture of apples rolling over the floor. And it was though the apples had made the decision and not her: she had to pick them all up, and then the train left…”

Dubravka Ugrešić’s gift is the struggle: internal and external – of longing for the seemingly impossible – simply to belong, and in peace. Descriptions of oppressive banality under communism mingle with the tell-tale vacant stupor of a person without a home, an address-less individual with no country or state, constantly in motion – unmoored due to outside circumstances.

Her words are precise, chosen with exquisite care. Much like a museum exhibit, many of her paragraphs are numbered, catalogued, and exact. Equally precise is the English translation.

The pain of exile is not pretty, but Ugrešić’s words capture a sadness that is quite beautiful. The real tragedy of losing one’s country and the baggage (or lack thereof) that goes with it, how this loss seeps into the cracks of everything, reaching the most nuanced recesses of one’s personal identity.

“I hear my heart beating in the darkness. Pit-pat, pit-pat, pit-pat…I feel touched, as though there were a lost mouse inside it, beating in fright against the walls. Somewhere far behind me the landscape of my deranged county is ever paler, here, in front of me, are steps that lead to nowhere.”

Dubravka Ugrešić is a literary powerhouse, and The Museum of Unconditional Surrender is a book to be savored again and again.

ABOUT THE REVIEWER

Natasha Ravnik is a first-generation Slovenian American writer living in the San Francisco Bay Area. She is fascinated by stories of cultural resilience, with a particular interest in women’s voices. Natasha is currently writing a fictional memoir based on Slovenian migration stories. Her documentary short film, “Moja Nonica – My Grandmother” was a finalist at the 2016 SEEfest Project Accelerator. A big fan of SEEfest, Natasha believes in the power of art to encourage dialogue, in the hope of finding mutual understanding. She is constantly searching for beauty and common ground.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs, as well as our mission to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!

The Legacy of the Non-Aligned Movement – The Dream of Peaceful Coexistence and Encouragement of Cultural Diversity

Did you know that the 1st Conference of the Non-Aligned Movement took place right in the heart of South East Europe?

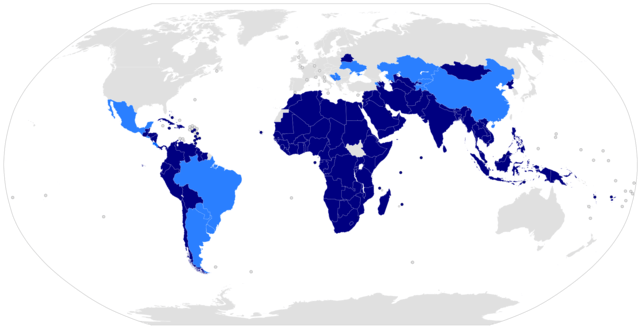

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) was formally established nearly 60 years ago—in one of the regions our festival covers—Belgrade, in today’s Serbia, then the capital of Yugoslavia. The first official conference of the non-aligned countries took place in September 1961, with 25 countries participating.

In short, NAM was founded during the Cold War by leaders from countries that aimed to establish the principle of peaceful coexistence and remain non-aligned with either of the two power blocs—the United States and the Soviet Union.

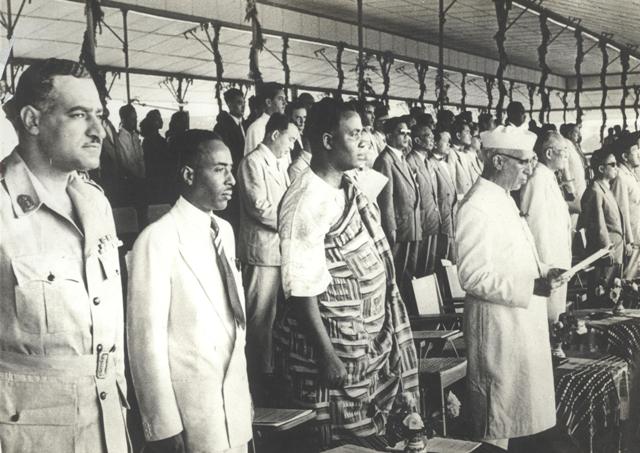

Leaders of the Global South at the Belgrade Summit 1961, © Museum of Yugoslavia, Belgrade

“In September 2021 we mark the 60th anniversary of the Belgrade Conference of the Non-Aligned Countries. Recent academic meetings and exhibitions (like the one held in 2019 at the Wende Museum in Los Angeles, titled Nonalignment and Tito in Africa) have at long last blown open the lid of inquiry on an important historical period and movement which offered an alternative approach to global affairs. Non-aligned movement forged previously unthinkable geographical alliances and challenged bi-polar global policies of the time. We need to explore Non-Alignment from a humanist, cultural, and public diplomacy angles, similar to what the world is trying to do today with a global agenda on climate change”, says Vera Mijojlić, founder of SEEfest.

Let’s take a look at the initial steps that led to the formation of NAM—which is the largest grouping of states just after the United Nations—and look at the deeper implications of how this movement worked toward peaceful coexistence.

To begin, the Cold War is directly responsible for the emergence of the terms, “first world”, “second world”, and “third world” —the western and eastern blocs, and the nations that decided to stay outside of these blocs.

To begin, the Cold War is directly responsible for the emergence of the terms, “first world”, “second world”, and “third world” —the western and eastern blocs, and the nations that decided to stay outside of these blocs.

Alfred Sauvy, a French demographer coined the term “third world” in his 1952 article, “Three Worlds, One Planet”. The “first world” was meant to refer to the United States and its democratic-capitalists allies like Western Europe, Japan, and Australia; and the Eastern bloc, the Soviet Union and “its Eastern Europe satellites” were considered the “second world”. The “third world” then comprised of the nations that chose to be non aligned, and which were also considered underdeveloped as many had just recently won independence from their European colonizers, like nations in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America.

In 1955, twenty-nine government representatives from Asian and African countries—representing nearly 54% of the world’s population—met in Bandung, Indonesia at what would become known as the Bandung Conference, “to discuss peace, and the role of the third world in the Cold War, economic development, and decolonization.”

Asian-African Conference at Bandung, April 1955

These nations called upon the meeting out of the frustration and alienation they felt as the non-aligned “third world” and decided to come together to dispel colonization through their unity and support for one another as well as their advocacy for other nations that were still under colonial rule.

It was at this conference that they established and signed a communique of the principles they would stand by, which included: “the promotion of economic and cultural cooperation, protection of human rights and the principle of self-determination, a call for an end to racial discrimination wherever it occurred, and a reiteration of the importance of peaceful coexistence.” (Office of the Historian)

These principles and their concept of banding together to support one another economically and culturally laid a lot of the groundwork for the Non-Alignment Movement. They figured as a majority of them were newly freed of their colonial ties, they would use this unity to build one another up through peaceful coexistence, the dismantlement of colonialism and racism, and the promotion of diversity.

SEEfest promotes cross-border cultural diversity

Promoting lesser-known regions, their history, heritage, and their cultural diversity through film, literary and cultural events is at the core of SEEfest, a cultural festival that “pioneered the concept of regional, cross-border programming with issue-driven films that tell a larger story about South East Europe (…) by presenting multiple points of view from this troubled region,” to quote from the festival’s mission statement.

On the occasion of the historical 60th anniversary of the first NAM conference, we look back at the world as it was then, and how a small country in the heart of South East Europe, only recently freed from the oppressive dominance of the Eastern bloc, took center stage in hosting a meeting of Asian, African and Latin American countries. Aside from politics, this conference would have a lasting cultural influence on people and artists of Yugoslavia: from The Museum of African Art, the first and only museum in the region entirely dedicated to the cultures and arts of the African continent, to several recent documentary films about NAM and upcoming magnum opus by acclaimed filmmaker Mila Turajlic, “The Labudovic Files” about the cameraman who filmed not just the leaders of the movement but preserved on film living history and cultural traditions of many nations.

“We look back at the main protagonists and at what deep sense of solidarity Tito was able to instill wherever he went on his extensive travels. There is strong evidence of trust between Nonaligned nations — something not only completely absent from but pretty much unthinkable in our present world,” says Vera Mijojlić, founder of SEEfest.

From Left to Right: Gamal Abdel Nasser, Josip Broz Tito, and Jawaharlal Nehru

NAM was headed by the president of Yugoslavia, Josip Broz Tito; the President of Egypt, Gamal Abdel Nasser; and the first Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru.

Josip Broz Tito, who played a pivotal role in the movement, achieved something no other Eastern European nation succeeded in doing until the fall of the Berlin Wall: he managed to distance Yugoslavia from the Soviets and retreated from the USSR-led alliance in 1948. As stated in Non-Alignment and Tito in Africa, Tito defied “Soviet hegemony to launch (Yugoslav) own program of socialist development.”

Through his foreign policy and anticolonialism, Yugoslavia strengthened its ties and influence in the ‘third world’. Tito’s legendary travels to Africa, Asia, and Latin America have been well documented on film, primarily by the state-funded newsreel service Filmske Novosti. The company still exists and serves as a treasure trove of unique archival material for scores of young filmmakers, scholars, and media organizations throughout the world.

Extensive travels and Tito’s meetings with leaders of non-aligned African countries led to “economic packages, military aid, technical support, and cultural and academic exchanges, it helped build factories, power plants, ports, hospitals, and research facilities in numerous African countries. In return, Yugoslavia gained access to African raw materials and new markets to trade its surplus consumer products.” (Non-Alignment and Tito in Africa)

Tito also strengthened Yugoslavia’s ties with other third-world countries in South America, notably with Mexico, and this, in turn, introduced Mexican films from the golden age to Yugoslav audiences across the country. This then led to the 1950s-1960s “Yu-Mex” craze, when Mexican music became so popular in the region that many Yugoslav musicians began covering traditional Mexican music. The documentary film by Miha Mazzini, “Yugoslav Mexico” from 2013 is dedicated to this cultural phenomenon.

Another notable thing Yugoslavia did under Tito’s leadership was aid the third world in anti-colonialist movements, and it was the Yugoslav delegation that first brought the demands of the Algerian National Liberation Front to the United Nations.

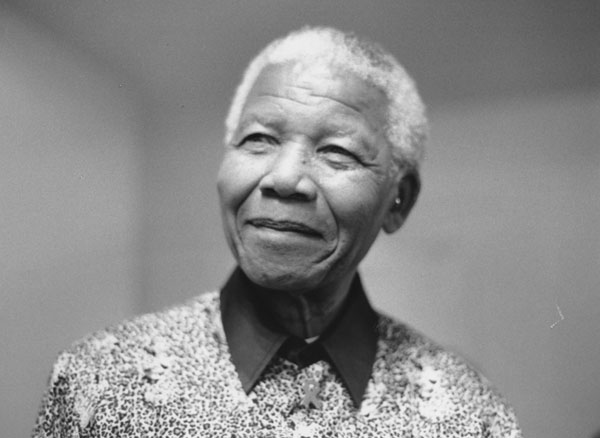

Nelson Mandela

Later, another important figure that would serve as a Chair of the Non-Aligned Movement would be President Nelson Mandela. From September 1998 to June 1999 he served as NAM’s 19th Secretary General. After the 7th NAM Summit of 1998, he relayed the discussions and outcomes the group had to the United Nations General Assembly during their 53rd session.

SEEfest will continue to highlight this, and other influential historical and cultural milestones of South East Europe. Stay tuned for the next update!

Post your comments and memories of this historic event below. And be sure to sign up for the SEEfest News so you don’t miss important announcements about the annual Festival!

Meet the SEEfest 2020 Jury

The Jury of the 15th SEEfest

Judging the films in competition for this year’s virtual edition of the festival are 21 members of the entertainment community who will choose the best feature, documentary, and short films as well as vote on the achievement in cinematography.

The Jury members for Best Feature Film are renowned actresses Joanna Cassidy and Denise Grayson, and former director of programming and founding board member of the Austin Film Society, Chale Nafus.

In narrative documentary jury, they are joined by award-winning producer, director, and camerawoman Michelle Paymar, IDA Documentary Awards Competition Manager Ranell Shubert, and writer/director George Paul Csicsery.

Producer Tessa Bell, editor Robin Katz and actress/director Melanie Mayron are judging short fiction; documentary filmmakers Christine LaMonte, James Tumminia and Åsa Kalmér are judging short documentaries; and Spanish filmmaker Nathalie Martinez, director of Animation Is Film festival Matt Kaszanek and photographer Brian McCarty are judging short animation.

Two cinematography juries, one for feature films and one for documentaries, feature six more distinguished artists: designer and documentary director Arnold Schwartzman, cinematographers Anette Haellmigk, Alan Caudillo, Attila Szalay, and David Frederick, and concept designer and illustrator, Milena Zdravkovic.

Meet the 15th SEEfest Jury here.

Filmmaker news: Another successful writer

Filmmaker Varta Torossian, who participated in SEEfest Accelerator this year to hone her pitching skills, entered the ISA Pitch Challenge (International Screenwriters Association) and was selected as a finalist. Congrats to Varta, and good luck with the next step!

Learn about more new creative voices here.

Films from the archives: Mexico in the Balkans!

Enjoy this entertaining documentary by Slovenian filmmaker Miha Mazzini about the unique YuMex, Yugoslav Mexico musical craze in communist Yugoslavia. The film is 45 minutes long and it is available for free on YouTube.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

If you like our programming orientation and the cultural mission of SEEfest, consider making a donation to support our work. Thank you!

FRIENDS OF SEEFEST

SEEfest program and activities are supported, in part, by the California Arts Council, a state agency; Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles County Department of Arts and Culture; and by an Arts Grant from the City of West Hollywood. Special thanks to ELMA, and the Hollywood Foreign Press Association for their continued support of our programs.

Follow SEEfest on Instagram and Facebook where we post SEE news as it happens!