Review – I Do Not Take My Name for Granted

I Do Not Take My Name for Granted: Four Short films by Saodat Ismailova

Reviewed by Amanda L. Andrei

March 6, 2023, at REDCAT, Roy and Edna Disney CalArts Theater

The longer you gaze at the steep cliffs, the more you start to see shapes of women. Vintage footage of Soviet tanks gives way to the dilating pupil of a tiger. And the image of women—whether preserved through oral tradition, a nation’s cinema, or a fading ritual of movement on a mountain—emerges from deep within the cultural memory of Saodat Ismailova’s four short films at REDCAT, curated by Jheanelle Brown.

Gulaim (2014) starts the journey, a monologue of the heroine Gulaim from the Central Asian epic Qyrq Qyz (40 Girls), a narrative preserved in the oral folklore of the Qaraqalpaqs, a Turkic group native to Karakalpakstan, an autonomous republic within Uzbekistan.

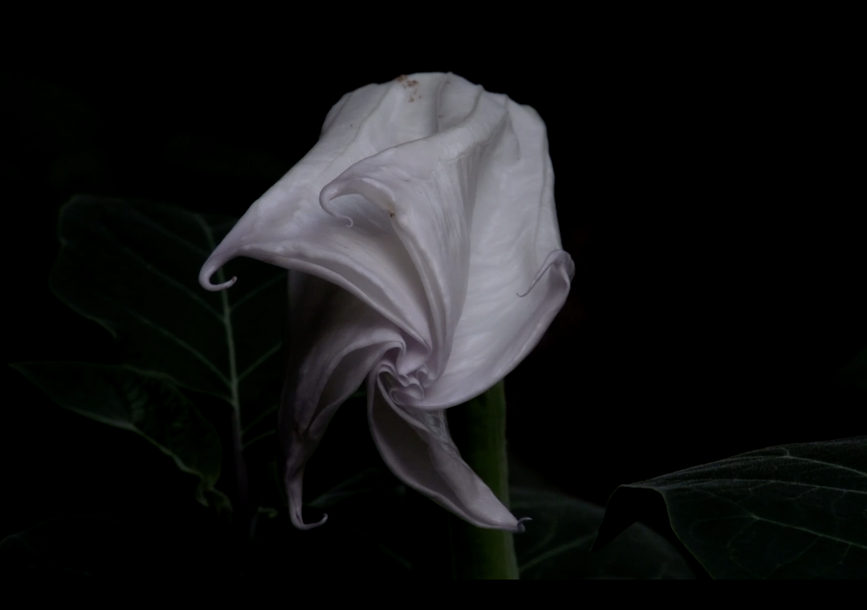

Cliffs bathed in setting sun rays mingle with closeups of a young woman’s face and hair, the blue flanks of a horse, and a blooming moonflower, as a narrator relates how her father used to shower her with affection in her childhood. Now she refuses to marry a man he has chosen for her, marking a new chapter in her life as she moves from favored daughter to something more liminal and uncertain.

The breathtaking landscapes and intimate details of hair, clothing, and animals—as well as surreal images of veils, chainmail, and a theatrical stage—draw the audience into both large and small scales of beauty and betrayal on ancient and modern levels.

The following film, The Haunted (2017), depicts an imaginary encounter with a Turkestan tiger that became extinct due to Russian colonization of Turkestan in the 1940s.

As sportsmen and military personnel hunted the tigers and the sacred animal’s habitats were converted into land for cotton crops, the tigers were declared extinct in the 1970s. A female voice quietly yet intensely mourns the loss of sacred love and connection over images of grainy black-and-white footage evoking colonization, which are juxtaposed against intense closeups of a live tiger’s eyes, whiskers, and deep fur.

Shots banks its former habitat are motionless amidst the river banks’ greenery, as if waiting for the empty space to once again be filled with soft pawprints and striped skin.

Her Five Lives (2020), commissioned as part of Asian Film Archive’s Monographs, a series of essays on Asian cinema, presents five different archetypes of heroines in Uzbek cinema from the past century, starting with Vyacheslav Viskovsky’s 1925 film, The Minaret of Death, based on a 16th century myth of the Bukharans, an ethnoreligious Jewish group in Central Asia.

Early silent black-and-white film of women as victims of patriarchy transitions into portrayals of women under communism, reform, perestroika, and eventually independence (albeit a confused one).

In contrast to the first two films, this short is faster paced and draws upon more recent cultural memory in the form of archival film, with some of the last footage from Ismailova’s 2014 film, Forty Days of Silence. It’s exciting to watch the transformation of the cinematic portrayal of Central Asian womanhood, making one wonder how to access and watch these films now.

The final film, Chillpiq (2018), depicts a group of girls climbing the ruins of Chillpiq, an ancient funerary structure founded by Zoroastrians and located in Karakalpakstan.

They surround a flag pole, tying rags and circling the pole in the light of the fading sun. From a visual standpoint, the film seems more like a documentary, grounded in realism and with steady shots of the young women as they climb up the mountain. But as they conduct their ritual in silent determination, there arises a feeling of quiet glory that only comes through steadfast devotion.

These contemporary women somehow know how to honor the earth and the unseen, and the earth and unseen return the honor.

While Ismailova’s films have been showcased in museums and film festivals, with her work currently held in collections of Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, this one-night event marked the first time that her films have been screened theatrically in Los Angeles.

Her films are a treasure, giving outsiders a rare glimpse into Central Asian ritual, history, and personhood. To see them in a cinema is a reverent experience, offering the chance to immerse ourselves in our own cultural memories and re-examine the myths, landscapes, and archetypes that we hold dear.

Reviewer Amanda L. Andrei is a Filipina Romanian American playwright, literary translator, and teaching artist residing in Los Angeles by way of Virginia/Washington DC. She writes epic, irreverent plays that center the concealed, wounded places of history and societies from the perspectives of diasporic Filipina women, and she translates from Romanian and Filipino to English. For more information on her work and upcoming events, visit: www.AmandaLAndrei.com

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!