Author in Front of the Mirror

Why Hortensia Papadat-Bengescu remains one of the most acclaimed literary voices of Romania

by Ioana Bîrjan

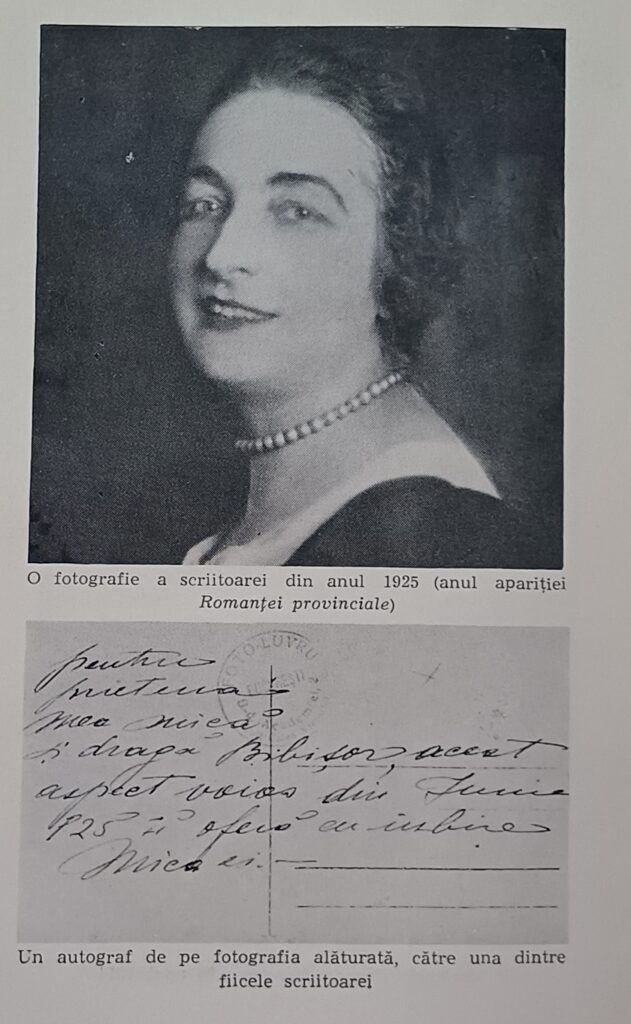

Hortensia Papadat-Bengescu is one of the most acclaimed novelists of the Romanian canon. Why did it take her so long to gain larger recognition?

Born into a bourgeois family that refused her the opportunity for university studies, Papadat-Bengescu found encouragement from a friend to pursue her calling as a writer.

This was no small feat in 1920s and 1930s Romania, where like in many European countries, men dominated publishing. Though her husband withheld his support at every turn, Papadat-Bengescu never relinquished her gift for translating thought into the written word.

Her encounter with Eugen Lovinescu, literary critic and founder of the Sburătorul circle, marked the pinnacle of her career. In the closing years of the 1920s and the dawn of the 1930s, she created her most celebrated achievement: the Hallipa saga.

“You cannot throw yourself, powerful, vigorous, and confident, into the waves of life without being carried to the harbor of happiness,”

Papadat-Bengescu wrote in the novella Marea, which translates “The Sea.”

These words encapsulate, with remarkable accuracy, Papadat-Bengescu’s vision of life. She dreamed of happiness throughout her days, and even in her darkest hours, near the end, she never abandoned hope. Though she had become but a shadow of her former self, she continued to write with undiminished passion, talent, and tenacity until her final moments, leaving behind a body of work through which we glimpse the spirit of Romania’s interwar years. Her singular style defies strict classification, yet the experience of reading her recalls that of encountering other great voices, such as Virginia Woolf. To understand what renders Papadat-Bengescu so distinct and unforgettable, one must first look to the era that shaped her, tracing her steps through the refined and turbulent society of interwar Bucharest.

In Romania, the close of the nineteenth century signaled not only the twilight of the so-called belle époque, but also the dawn of literary modernism. This modern era marked the first moment when Romanian literature claimed a larger place upon the world stage. It was during this period that some of the nation’s most important voices, among them Papadat-Bengescu, began to publish their work. For a broader perspective, we must recall that between 1914 and 1945, the entire world underwent profound and irreversible change.

Before 1914, European literature was shaped by the Balzacian style, named after French novelist Honoré de Balzac (1799–1850). Balzac held that literature should mirror life, and his works are therefore rich in precise descriptions of real places and people who look and act as “real” ones do.

This approach centered on external actions and events that befall the characters, with little exploration of their inner worlds. With the advent of modernism, however – and under the sweeping influence of Sigmund Freud’s (1856–1939) revolutionary science of psychoanalysis – both psychology and literature turned their gaze inward. Marcel Proust (1871–1922), another French writer, developed a style later known as “Proustian,” focusing not on places, but on sensations and the intricacies of the mind, with the character’s psychology as his central theme. His work laid the groundwork for the “stream of consciousness,” the narrative technique that came to dominate the first half of the twentieth century.

What happens when the two styles converge?

The result is a distinctive narrative voice, the very one that Romanian modernist Papadat-Bengescu wove throughout her novels. After the First World War, Romania turned its gaze westward, seeking cultural inspiration and aligning itself with the major literary currents of Western Europe. Authors such as Papadat-Bengescu began to leave their imprint on the broader European canon.

Born in 1876 as an only child, Papadat-Bengescu began writing stories in her youth. These early experiments blossomed into a lifelong passion, though her family offered little encouragement. In the male-dominated society in which she was raised, women were denied the right to vote; while they could, in principle, attend university, they were often discouraged from doing so. Her parents forbade her from continuing her studies after high school. She later married a man who not only withheld his support for her literary ambitions, but actively sought to thwart them.

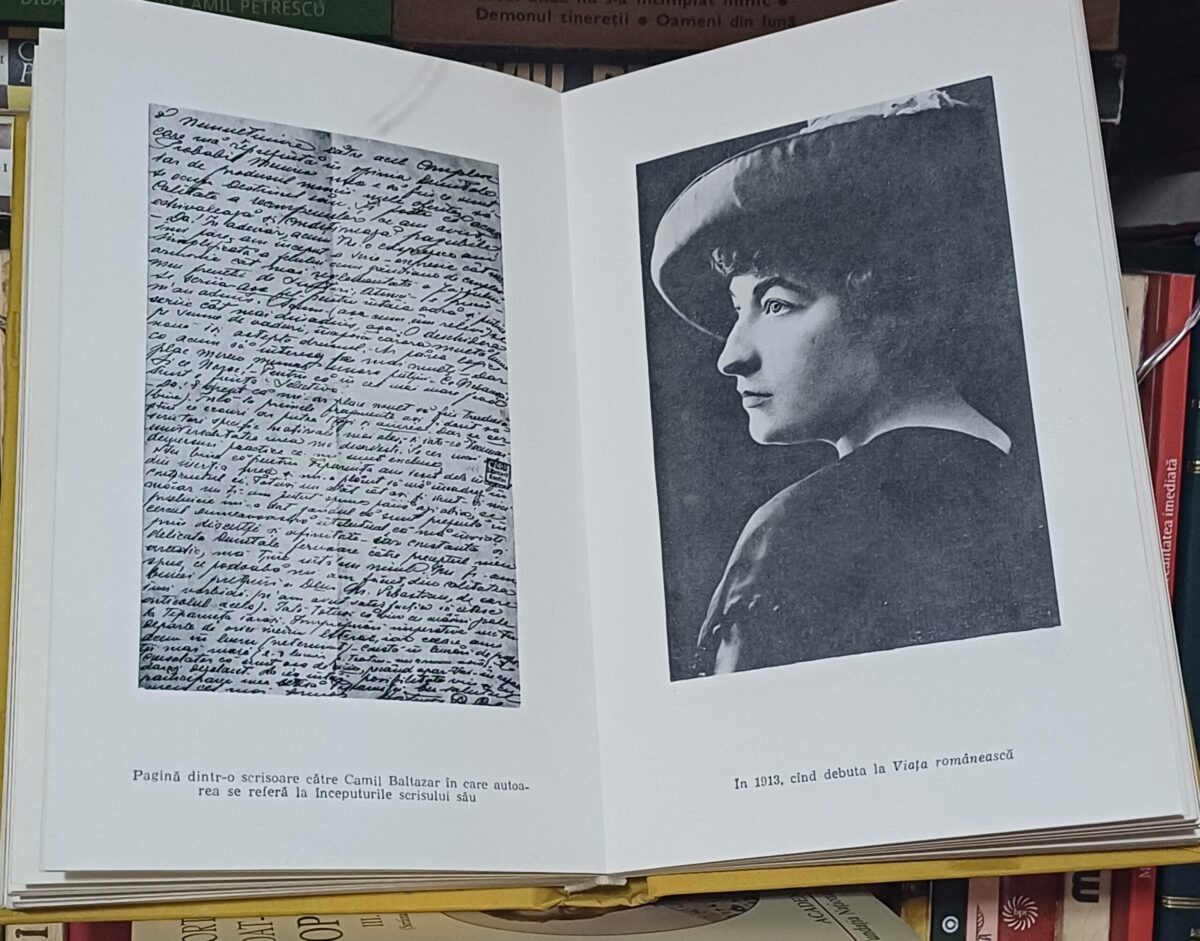

Although the newly united Romania adopted the French model of thought and proclaimed that society was open to all, a deeply rooted belief persisted: a woman’s first duty was to her family. Papadat-Bengescu, unable to pursue public literary ambitions, turned instead to letter writing, and these were no ordinary letters, but graceful, artful compositions sent to her friends. In them, short stories often emerged, revealing the beauty of her style. One friend, recognizing this gift, persuaded she to take her writing seriously and seek publication. It was a simple but decisive moment, the sincere encouragement of a dear friend, and from that point on, she wrote without pause until her death in 1955. Her most celebrated creation remains the Hallipa saga, a six-volume chronicle of a family navigating the complexities of Romanian society during the interwar years.

The saga comprises one short novella and five novels, from which the second one has been first translated into English, French, Italian, and German and a few other languages, under the title A Concert of Music by Bach, identical to its Romanian original, Concert din muzică de Bach. Curiously, this sole translation did not mention the others, not even a note to inform readers of the larger cycle. This may be because A Concert of Music by Bach is widely regarded as Papadat-Bengescu’s finest work and the pinnacle of the saga.

The novel is polyphonic, unfolding through multiple points of view.

This narrative form invites readers deep into a social gathering designed to satisfy the ambitions of the newly risen society to which its characters belong. Music, however, serves merely as a pretext to explore the intricate hierarchy of wealthy Bucharest families. In this world, greatness is measured by a relentless race for success and a desperate longing to be accepted into the highest social circles. Bengescu conveys this with subtle wit, showing how, during the Bach concert, each attendee strives not only to interpret the composer’s score, but also to perform their own “human score” — the most polished, socially acceptable version of themselves. Papadat-Bengescu’s characters feel vivid and tangible, their inner lives rendered with precision as she captures the complexities of emotion with rare accuracy.

Other authors of the period, such as Camil Petrescu and Anton Holban declared that these new literary techniques represented the most truthful way to write in the modern age that emerged after the First World War. Papadat-Bengescu, by contrast, never set down such theories. She simply stated that she observed the people around her, wrote about everyday events, and explored her characters’ emotions. For her, writing was both an escape from the constraints of life as a bourgeois wife and mother, and a form of confession, a way of speaking her innermost thoughts through the voices of her female characters, as though gazing into a mirror. Not a literal mirror, but one reflecting the depths of her soul. This is why, after publishing her first novel and a collection of short stories, she became recognized as the foremost female literary voice of her time, a distinction affirmed by the Sburătorul literary circle.

For Papadat-Bengescu, membership in literary circles ensured a place in the Romanian canon.

Younger Romanian women authors, such as Lucia Demetrius and Ticu Archip, were also part of Sburătorul and, in the 1930s, alongside several male colleagues, authored an article naming Papadat-Bengescu “the greatest European author of Romania.” At the time, Romanian literature had yet to gain widespread recognition across Europe, so the honor remained largely within national boundaries. Her reputation was further hindered by the delay in translating her works.

In 2005, however,Scrisul Românesc Publishing House, published an edition of A Concert of Music by Bach, translated from Romanian into English by Ileana Alexandra Orlich. (ISBN: 9733804568).

Two years later, at Cluj University Press, the same translator expanded the project, producing a trilogy – The Hallipa Trilogy – by translating both the first and third novels of the saga. (ISBN: 9789736105807).

Beginning such a multi-volume work with its second volume can be disorienting for readers, which is why it is worth becoming acquainted with the Hallipa family and their story before embarking on the series — an opportunity we now have.

Even though the final two novels and the introductory novella remain untranslated, readers can still “live” alongside these characters and come to understand their intertwined destinies.

Why hasn’t the entire saga been translated yet?

The politics of translation are complex – who gets translated and why? A fair question and one too meaty to unpack here. One factor with Papadat-Bengescu is that Romania is a smaller country of Europe, and one whose literature has been more known within its borders. The language barrier plays a role here, though 24 million people can speak and read Romanian. It’s not nearly as popular – or possible – to study Romanian in American universities as it is to study, say, Spanish, French, or German.

Additionally, most twentieth-century Romanian authors wrote exclusively in Romanian, with the exception of those who emigrated and adopted French. Then the nation endured the direct upheavals of both World Wars, followed by a harsh communist regime that placed strict controls on publishing. In the 1950s, writers such as Papadat-Bengescu were outright forbidden to publish. By the 1960s, the new leader of the Communist Party authorized the study of Romanian literary modernism in schools, but even then, these novels were not traveling beyond the country’s borders or finding translators for an international audience. This is what makes the translation of Papadat-Bengescu’s work into English such a remarkable and long-overdue event.

So why does Papadat-Bengescu remain one of Romania’s most acclaimed literary voices? The answer, I believe, is simple: her work remains relevant because she captures the emotional landscape rather than mere external action. Societies change, certainly, but love, as an emotion, resonates now just as it did a hundred years ago. The same is true for the enjoyment of classical music or jazz, the pleasure of meeting with friends, or – in my own case – the quiet satisfaction of writing for oneself, whether or not those words ever see print.

As a young author, I have learned from her how to delve deeper into a character’s consciousness, to understand them more completely and in doing so, to understand myself. Even though only three of her novels are currently available in English, I wholeheartedly recommend them; that said, I’m looking forward to a day when more of her works are rendered into multiple languages – and not just English.

I hope readers will enjoy this glimpse of history as much as I do, as told through the eyes of characters who reflect so much of ourselves – for better, and for worse.

Ioana Bîrjan (b.1997) is the author of Vârsta Iubirii which translates into English as The Age of Love (Heyday Books, 2023). The novel is inspired by the Lady of the Camellias and the opera La traviata. She earned a bachelor’s degree from the Faculty of Letters, Ovidius University of Constanța, where she is now a graduate student in the Romanian Studies program.

Read more of her work in magazines, in anthologies, and on her blog: https://scrierileioanei.wordpress.com/

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!