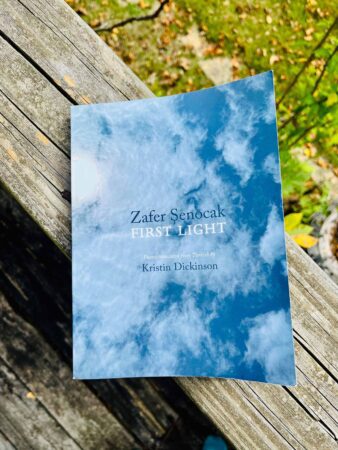

Review: First Light by Zafer Şenocak

| Author | Zafer Şenocak |

| Translated By | Kristin Dickinson |

| Genre | Poetry |

| Language(s) | Turkish, English |

| Format | 160 Pages |

| Publisher | Zephyr Press |

| ISBN | 978-1-938890-30-7 |

Reviewed by Allie Rigby

What does it mean to exist in one place, physically, but mentally and emotionally exist elsewhere, simultaneously suspended in past, present, and future? Such time-warped entanglement ricochets throughout Zafer Şenocak’s bilingual poetry collection, First Light, translated from Turkish into English by Kristin Dickinson (Zephyr Press, 2024).

Many of the poems speak to the ideas of memory, language, and home, home being an ethereal concept often–if not ever so slightly–out of reach; accessible in wisps, dreams, and impressions that linger as briefly as morning light.

Şenocak’s poems ache with longing and acknowledgments of human contradictions. The original poem unfolds on the left page, in Turkish, and on the right lays the English translation.

In the poem, Muammaydun or I was a riddle (pg. 68-69), the speaker’s voice aches with loneliness and the universal desire to be known:

“I didn’t want to be an I

I wanted there to be someone

Yearning for me

My faithful companion

When you reach me

Let me be known” (Lines 16-21).

The “you” is an especially compelling address in this poem and throughout the collection. Is “you” a lover? The reader? A deeper, spiritual companion? The “cosmos” as Dickinson writes in the opening text “Unraveling the Self in Translation”? All of the above? With the “you” address, readers are brought into an intimate conversation between the speaker and someone. How readers interpret the “you” will influence each subsequent reading of the poem. But rather than get too stuck on who this “you” may be, I ask myself what the poet Brynn Saito encourages her students to ask themselves, when reading a poem for the first few times: how does the poem make me feel?

After reading I was a riddle I initially felt soothed by the longings I shared with the speaker; I also felt forlorn that loneliness was so inevitable. The repetition of “I” in Line 16 has a sense of contraction in itself–only through the “I” can the speaker express who they do and don’t want to be, and how to break free of the loneliness of the singular “I” is simultaneously impossible and desired.

The last two lines provide the solace, the hope, that someone, or something, will enter the speaker’s life and see them truly. Does this happen at death? Or before, via spiritual companionship? Or perhaps with deep friendship? Like many poets whose writing I admire, Şenocak does not answer it explicitly, but rather, lets us revel–and struggle–with the questions.

It’s impossible to ignore the role of language in any work of translation. Those who are familiar with Şenocak’s impressive canon of work, which according to his bio on Zephyr Press, includes “ten books of poetry, seven novels, and five essay collections” may know that he wrote much of his earlier work in German first, rather than in Turkish. Zephyr Press published Door Languages in 2008, which Şenocak wrote in German and Elizabeth Oehlkers Wright translated into English. First Light was written in Turkish first, as is much of Şenocak’s recent work. Translation is an art and an interpretation, the initial language of a text will influence the subsequent translations.

The relationship between language and home is deeply intertwined in this collection. In Kalbini üzme or Don’t trouble your heart (pg. 30-31), the poem flows from the title as:

“May the dust surrounding it

Never tire you

Neither home nor homesickness will come of that dust

You’ve tried enough

To make a home at the water’s edge” (Lines 1-5).

What troubles the speaker here is not the inevitability that dust falls around the heart, but rather the exhaustion that comes from this dust. There is a gentle acceptance in this address, an invitation to imagine a different kind of home: whatever actions the addressed “you” has made to make a home have not succeeded. The rich image of making a home at the water’s edge is once again soothing and promising, and yet, the speaker here reminds the “you” that they can pause that home-making attempt.

What then, does it mean, to forgo making a home? Or is home not a physical thing to make, but only possible in the form of language, itself? To be at home in language.

To–as Şenocak closes that poem–“Let the knots in your throat open.” Each poem then, an experiment into untying more of the ropes that bind us.

Allie Rigby is a poet, editor, and reviewer with roots in Orange County, California. She is the author of Moonscape for a Child (Bored Wolves, 2024) and the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship to Romania, where she taught creative writing at Universitatea Ovidius din Constanța. She holds a master’s degree in English: Creative Writing from San Francisco State University. She enjoys connecting with people to develop and share stories that generate cross-cultural dialogue, solidarity, and change. For more of her work and upcoming events, visit www.allierigby.com or @allie.j.rigby.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!