Review: Sevdah: Elegy for a South Imagined

| Author | Malina Stefanovska |

| Genre | Nonfiction |

| ISBN | 978-1-952799-47-1 |

| Format | 88 pages |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | University Press of the South |

Reviewed by Robert J. Hudson

Sevdah, written in 2023 by Malina Stefanovska, captures “a feeling of intense longing that brings at the same time sadness and happiness. the Balkan version of the famed Portuguese saudade, nostalgia for a lost homeland, youthful dreams, past loves, or even for things that never were.” Choosing this as the title for her memoir, which bears the subtitle Elegy for a South Imagined, Stefanovska does wax nostalgic for the rich and eclectic “South” of her youthful summers, interwoven in six chapters and replete with genealogical vignettes, family legends, distant reveries, exemplary lives lived, and less than exemplary lovers.

But why should the story of one individual’s experience interest us? Why don’t we, like the author’s preteen son Ted from the first pages of her story, simply give in to the foreignness, the lack of context, the stifling heat and our inability to own anything in the narrative of another?

In 1580, at the conclusion of his introduction “To the Reader,” pioneering essayist and Renaissance man Michel de Montaigne forewarned and dismissed those who embarked to read him, admitting, “I myself am the subject of my book: it is not reasonable that you should employ your leisure time on a topic so frivolous and vain. Therefore, Farewell” (trans. M. A. Screech, Penguin Books, 1987). Montaigne would, nevertheless, continue over 107 essays and some 1,300 printed pages to demonstrate his thesis that “Every man bears the whole Form of the human condition” (ibid, p. 908), establishing himself as a model for humanistic introspection and the Essays as a veritable bible for living, as suggested by Orson Welles and others.

Stefanovska does not ask quite as much of her reader. In a beautifully recounted account of nostalgic sevdah, she conveys a sensual and sensory experience of her “South.” This South is, of course, South East Europe, the Balkans, the interest of SEEfest and our diverse readership. She recounts the summers of her youth spent in Bitola “at the southern tip of Macedonia,” where both of her parents and generations before them were born and lived their lives. This is the setting of Stefanovska’s cultural and familial memory. And truth is, as they say, stranger (and often messier) than fiction.

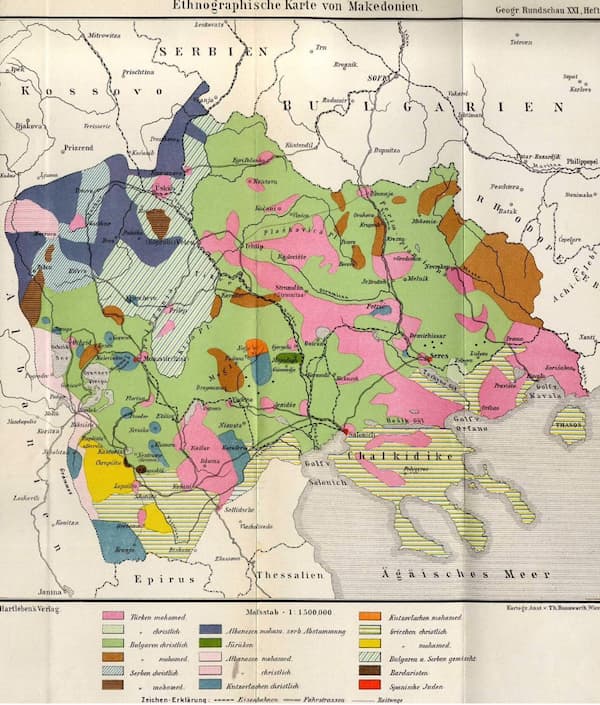

Could it be otherwise for Macedonia? In the French language, that of Stefanovska’s scholarship, the common noun “macédoine” is an antonomasia derived from the proper noun Macedonia and, in the culinary world, it is the term used for fruit cocktail or mixed vegetables. If we examine ethnographic maps of the region (like the one below from 1899), the origins of this idea of merging and integrating, while maintaining distinct identities, rings true for this region – as well as for Stefanovska’s account that blends (and not always neatly) Slavic, Greek, Vlach and Romani peoples, along with transient Africans, Arabs, Serbs and others. The Macedonia she describes is a vibrant mosaic of legend, myth, folklore, tradition, rite, common beliefs, colors, food, smells, etc.

Mosaic as metaphor here is deliberate. Bitola boasts some of the most remarkable examples of Ancient Greek mosaic (e.g., the UNESCO protected Heraclea Lyncestis). And Stefanovska is not indifferent to the deep, diverse past of this region, especially as she mentions Bitola as the birthplace of Filip the Macedonian, father of Alexander the Great. However, she does so almost in passing, relating how her own grandfather felt about sharing a name with this colossal figure from the past.

Sevdah is not a political history, but rather a familial history. Very little mention is made of the Greek or Bulgarian refusal to recognize Macedonian language, identity or ethnicity; however, she does include the story of a father slapping his ten-year-old son – the only ever time he would ever do so – for crying, in a mere act of mimesis with his classmates, when the Yugoslavian king was assassinated, which is telling.

Not a regional or political history, Sevdah remains anthropological as it deals with human relationships against the backdrop of a both mythified and palpable setting. Indeed, in an email exchange with Stefanovska, she admitted that the idea for the memoir germinated in part from her desire to teach a course at UCLA on border crossings in Europe, focusing particularly on the Romani.

In my teaching at Brigham Young University, I adopted her book for my European Studies seminar on “Regionalism,” as it offered rich and poignant first-hand anecdotal evidence to highlight the struggles, joys, values and interests of Macedonia and the peoples that inhabit this region. It was, I might add, an unmitigated success among my students, who would return to it in class comments throughout the semester.

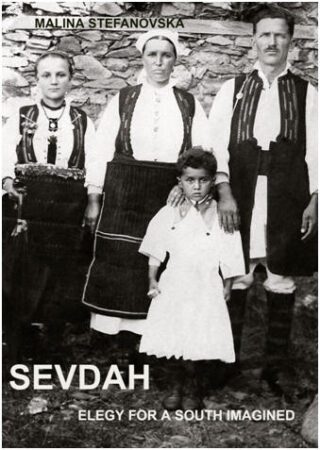

Above all else, Sevdah is familial. On its front cover, it bears a family photo of the author’s father as a child, standing with his older sister and parents, all donning traditional attire. As the one piece of “photographic evidence” in the volume, it is an image that the reader can return to frequently, with each new revelation from the author. In a sense, as memory builds upon memory, the memoir comes together somewhat like a Patrick Modiano novel, as a holistic image progressively develops.

Here, a handsome, blue-eyed Slavic pater familias stares through the lens of the camera into the eyes of the viewer, with an evident pride in his young family and hope to provide them a better childhood than his own – yet, with no idea, at the time of the photograph, that his ill-fated, ten-year trip to America would coincide with the Great Depression and that his beautiful teenage daughter (to the left of the photo) would die while he was away.

We also see the sternness of his wife, who “never sang, and told no stories,” and we begin to understand her jealousy and passion felt for the mystical man to her left who possessed so much more freedom to roam than she did. We even recognize the dark, penetrating gaze of the young boy who would grow from poverty to a diplomatic career, and one day become Stefanovska’s cherished father.

Stefanovska also explores her more affluent, Greek speaking maternal line, which is itself marred by a deep secret of family murder: her grandfather mysteriously shot and killed his son-in-law for reasons the author attempts to unravel. Along with tales of her maternal family, Stefanovska also shares the story of an admired paternal aunt, an effervescent woman with a “sunny temperament,” who overcame local gossip and judgment as a divorcée, socially deemed as a “loose, unleashed woman, living outside of the moral order” and something of a Slavic protofeminist.

As familiar as it is familial, Stefanovska’s memoir concludes with the story of an early love affair. As a student in Belgrade, she shared part of her life with a Roma man, whose shared interests in philosophy, poetry and politics – and South Balkan heritage – tragically gave way to distrust, possessiveness, alcoholism and physical abuse.

Never easy to read, Stefanovska’s vulnerability remains deeply impressive, offering a rare glimpse of shared humanity and an affirmation that not all stories have a happy Hollywood ending, that our lives are also defined by decisions to leave. Her tale is one of exiles, of roads taken and others abandoned.

Image: An older photo of the city of Bitola.

Along with the scent of mulberries and the admitted nostalgia induced even today by Turkish names, Stefanovska also tells of the emotional encounter as an adult in Paris, witnessing men bearing a heavy haul of Macedonian red peppers, pečeni piperki, at the Gare d’Austerlitz, and another gesture of a Macedonian father in the metro tenderly kissing his young son in a recognizable way, both of which transported the author instantly to the Bitola of her youth.

Drawing to a close with an account of her own motherhood, a topic that bookends her memoir, from young Ted to her adopted daughter Maya, we can recognize the truth that our memories define us and inform life’s decisions. Snapshots and static histories are helpful, but an accounting of the process and the layers of humanity are far more valuable to understanding.

Like Montaigne, who expressed the impossibility of painting a sunset, Stefanovska is not attempting to paint a realistic portrait here; her aim is to capture “the passage” of becoming, passing from one state to the next. She elucidates snippets of memory that engender sevdah. She recounts a story of a South that no longer exists, and indeed, may never have existed, except in imagination.

Sevdah is available for purchase, in both English and French, from the University Press of the South.

Robert J. Hudson is a professor of French literature, cinema and culture in the Department of French & Italian at Brigham Young University.

Born in Arkansas and raised in Kentucky, Bob feels about his own “South” in ways that are quite akin to the ways Malina does about hers. Educated at UCLA, he is a scholar and translator of poetic verse from Renaissance France, focusing particularly on the importation of the Petrarchan sonnet from Italy to France, and the ways that literature and film serve autobiographical ends.

SUPPORT SEEFEST

Not a member yet? Become an art patron with other SEEfest arthouse aficionados in support of great events and programs. Our mission is to keep you informed about initiatives from our wide network of fellow cultural organizations.

We Welcome YOU!